Actions Speak Louder: The Spoken Word

by Hannah Stewart

Introduction

What does the word “slam” mean to you? Perhaps you see someone getting thrown against a wall, or a plate clattering on the counter. Maybe you think of a verbal beating, a daggered speech aimed in your direction. You may even conjure up an image of one of the recent presidential debates or campaign ads. But one very special group of people doesn’t see one word. They see four, and those words are “Spoken Like a Metaphor.” The S.L.A.M. club on campus here at The University of Akron is a wonderful place for poets and dreamers alike. It’s a place of expression, of beauty, and of words. It’s a place where the writer in all of us can be expressed freely, in a welcoming and encouraging environment. At S.L.A.M. club, poets have the freedom to come alive, find their voice, and take a stand–just as they’ve always secretly longed to do.

Poets Welcome

To join S.L.A.M. club, there is only one thing you must know how to do: write. While this club places emphasis on performance and poetry, all writers–even aspiring writers that haven’t quite gotten their bearings yet–are welcome. Once you’ve joined, you can learn the tricks of the trade by watching and listening to the other members. Many of them love talking about their art of spoken word, and are more than willing to help you out.

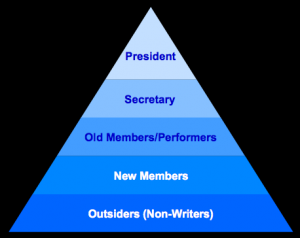

Upon entering the S.L.A.M. club, one is met by both a relaxed, welcoming, chill atmosphere, and a very clear–though unspoken–structure. Newcomers and outsiders, while certainly not frowned upon, are easily identified by their quiet demeanors. The way older members relate with them is friendly, but does not have the sense of camaraderie and familiarity that is evident when they interact with one another.

When one observes this interesting group, he or she can easily see the chain of command in place. Jasmine, the president and founder of the club, has a very calm, cool, and collected aura to her. One look at how she presents herself and how the other members respond to her makes it very clear that she’s in charge of this powwow.

Regina, the secretary, is not often able to make it to meetings, but everyone knows her position through the weekly email of reminders she sends out. She is a huge help to Jasmine, and everyone knows how heavily the group relies on her.

As the meeting wears on, one can see the influence that the other performers have. They freely give input as to what should happen during the meeting, and are not afraid to respectfully contradict what their president says. When a performer speaks, especially during an evaluation of any practice performance, everyone listens.

Below them, many of the members are “closet slammers“–those that know how to give a performance but have never had the guts to go to a real slam and compete. These are the next rung down on the metaphorical ladder of power, and would be where most of the club falls. A mutual love of words and expression, and an understanding of the rules bind all of them together.

Walk the Walk

There are very few rules in S.L.A.M. club. In fact, to the casual observer, there may appear to be none at all. But to anyone that spends time on the inside, they become very clear. While the consequences for breaking the rules may not be extremely hefty, they are there, and they are dutifully followed.

The first unspoken rule is one of encouragement. Every writer, no matter the genre, has been burned, dissed, hurt, or otherwise torn down by critics at some point. Because of the scars and insecurities caused by these beatings, every writer makes a promise to herself that she will never cause the same pain to a fellow writer. Critique is a very large part of any group of writers, and S.L.A.M. is no different. But as is common among all writing groups, this criticism is delivered in a positive way. When a member stands and gives a practice performance, the other slammers will offer feedback for improvement. But, rather than focus on the bad, they snap their fingers, praise the good, and make mention of things that need improvement. Much of the time, they place the focus on themselves, to make their comment feel less hurtful. For example, one might say, “I got a little distracted when you hesitated like that,” rather than “don’t hesitate too much, it’s distracting.”

The second rule of S.L.A.M. club is a very simple, though slightly strange one that is accepted in every slam lounge. In slam, you don’t applaud. You snap. The gesture originated in ancient Rome, where there was a set format for expressing appreciation at a performance (Harrington). In those times, the audience members would snap, then clap, and finally wave their handkerchiefs or the ends of their togas as their excitement or pleasure increased. In modern times, snapping is used as a respectful form of applause in poetic performances because of their nature. A poet can only speak so loud, and often chooses to use a softer tone in the more tender parts of a poem. The audience is encouraged to respond whenever and however they feel proper, so the softer snapping is less distracting to both the performer and the audience than clapping. Occasionally a newcomer or outsider breaks the rule. There is no great punishment for doing so, besides perhaps a stern glance from Jasmine if the perpetrator should know better.

The third rule of S.L.A.M. regards the poetry itself. In slam poetry, there are no rules. There is no set scheme or meter. These are stylistic choices left entirely to the the writer to make. The rule here is that because there are no rules in writing the poems, judgments and critiques are not to be based upon the style of the poems themselves. Someone who breaks this rule–besides a newcomer that simply does not understand that slam poems do not have a specific format–will most likely be rebuked by another member of the club, or have to nurse his or her pride when no one agrees with their critique.

In S.L.A.M. club, you are expected to give your best. Whether you take part in a performance exercise, practice performing an original work, or help critique another performer’s work, you have to take your best shot at it. You may not do a great job, but as long as you do it to the best of your ability, everyone is happy. This constitutes the fourth rule of S.L.A.M. club.

Finally, in S.L.A.M., nothing is too far out there. Performers are taught to think outside the box, and cross the lines of their comfort zones. For some, this may mean cutting out the action, staying in one place and using only their voice to convey a message. For others, it may mean jumping around, going crazy on the stage, and acting like a drama major. This helps the performers of S.L.A.M. to find their style and their voice.

Talk the Talk

Every slam poet has a unique style. At S.L.A.M. club, new performers are encouraged to find their voice by exploring the different tricks of the trade. Vocal inflection, tone, meter, body language, singing, and acting are all important to any slam performer.

There is an old adage that states, “Actions speak louder than words.” This may be true, but they also influence words. Spoken word lifts the ink from the page, but without the help of actions, it can do nothing but hang in the air like a useless pollutant. The performers can’t just breathe the words. They have to breathe life into them. It takes some or all of these tricks to do so, and where these tools are placed in the hands of a master performer, you will find power. Magic rests in the hands of poets, but they must use their whole body to express it to the world.

Some poets choose to read their pieces while standing still, with a monotonous voice throughout, to elicit a sense of irony. But most of them carefully choreograph their poems, memorizing them and practicing different ways of expressing them. A good performer can sway the audience to feel anything.

Every good poet has a different and unique meter when they speak, which comes naturally to them. This is what slammers focus on drawing out, emphasizing, and turning into their style. They have their own facial expressions, body motions, and vocal inflections that can be used to infuse the performance with personality and emotion, which becomes a part of their style and voice.

By Any Other Name…

Every voice comes with a name. For a slam poet, these names serve as identities. Just as an actor hides behind a character, a poet’s stage name give them a presence, allows them to be something different than themselves.

Slam performers often take on stage names when they perform at slams or in public. They put a lot of time and care into choosing these names, and most names have a good deal of meaning or purpose behind them. For example, Russel calls himself Reality. He–like me–is a Christian, and uses his poetry to talk about the truth of God, the hypocrisies of life, and other important topics. He chose the stage name Reality because that’s what he stands for and what he wants to bring to his listeners.

During a S.L.A.M. club meeting, each member appears to have two separate identities. For Sasha, this is especially evident. During discussions, critique sessions, and so on, she is a very happy, upbeat, fun-loving person. But when she stands up to perform, she becomes PassionSoSickFlow, the passionate performer with deep, important things to say. Because each member has these two broadly varying characters, the group as a whole refers to them accordingly. When the club is just talking, everyone goes by their real names. But when someone is sharing her poetry or talking about a performance, she goes by her stage name.

When a performer takes his stand upon the stage, he becomes his stage name. The side of him that is without fear, that can speak out boldly and perform with courage, is all you see. The most shy and quiet of poets can put on their stage name and become an enigmatic, dynamic performer that brings an audience to their feet, or even to their knees, if she wishes. But event the best of performers had to start by practicing somewhere.

Come Together

S.L.A.M. club has a few obvious rituals, such as their weekly meeting and semester slam. Every Monday night, S.L.A.M. club meets in a small room on the top floor of the Student Union for a few hours. It’s a time for writing, practicing your performing skills, hanging with your fellow slammers, and learning about the techniques of slam.

Once a semester, the entire club gathers for a real poetry slam. Some compete, others go just to watch. It is modeled after the traditional slam formant, and gives the members a chance to participate in a real slam in a somewhat less threatening environment among their peers. The location changes, but usually takes place on campus, often in one of the rooms in the Student Union.

However, these two well-known rituals are not the only ones. There are many unspoken rituals, which I have listed below:

- Weekly Vocabulary: Every Monday night, Jasmine brings a list of new and interesting words for the slammers to write down and look up at home. It is a fun way of expanding the poetic vocabulary and adds variety to the words each poet will use in the future.

- Critique Sessions: These take place during the weekly meeting, whenever a slammer chooses to give a practice performance, or after each member completes an exercise. In essence, a critiques session is held after each performance to pick apart what the performer did and didn’t do well and offer helpful encouraging feedback to them. The point is to help them improve their skills and focus their voice.

- The Emotion Exercise: One of the many exercises common in S.L.A.M. club. This one sticks out because during the first meeting I attended, Jasmine decided it would become a permanent staple of the weekly meeting. For this exercise, every member must get up and perform the same poem. Everyone’s name is placed in a hat, and as each one is drawn the previous performer calls out an emotion. Whoever’s name is on the piece of paper must perform the poem with the chosen emotion, using any means necessary. Each performance is followed by a critique session. The purpose of this exercise is to both help performers get out of their comfort zone and teach the group different ways of expressing emotions.

The rituals of S.L.A.M. club are as important as slam poetry itself. Slam is a powerful mixture of words and action, and an incredible form of self-expression. The rituals of S.L.A.M. club bring slam poets together, and help them improve their craft. This in turn brings greater inspiration and lends greater power to the poets that partake of it.

And in the End

Slam poetry is a remarkable, powerful thing. But it cannot be so on its own. The people make the slam, not the words. Without the people, it’s just another classroom in the Student Union. It’s not until the vast variety and make up of S.L.A.M.’s members enter that it comes alive, and it becomes a place of magic. As they breathe their words the room fills with laughter, heartache, and every emotion known to the human soul. It’s a place where the quiet poets come out of their shells and the loud ones learn to be still. It’s a place unlike any other, where even the most unlikely voices can be heard loud and clear. It’s a place where everything is Spoken Like a Metaphor.

Glossary

Droppin’ It–This is a phrase that is used to describe someone whose performance is mind-bogglingly well done. If a poet elicits the poem’s intended emotion very strongly, he or she is “droppin’ it.” On occasion, this term can also be used to describe someone that helps a poet with his meter through vocal percussion, as well as someone free styling a poem.

Finding Your Voice–The leaders of S.L.A.M. often use this phrase when helping new poets on stage. It refers to the vocal style, stage presence, and poetic style of a performer.

Free Style–There are two meanings to this term, denoted by the context in which it is used. It can be used to describe a poem that does not employ a scheme, or to describe a poet that is making up a poem as he or she speaks it.

Meter–This is a term that refers to the constant rhythm or beat of a poem. If you were to count the number of syllables in each line of poetry, you would find the meter.

Sacrificial Poet–The sacrificial poet is a slam poet that is offered up by the host of a slam. His performance is not counted in the competition, but used to gauge the judges. The sacrificial poet is typically someone young and mediocre, used to establish a baseline for the competitors.

Scheme–Scheme is an abbreviation, used to refer to the rhythm scheme of a poem. Some poets employ a constant, continuous, steady scheme, while others employ no scheme at all. This is a stylistic choice made by each individual poet.

Slam–A slam is a poetic performance competition. Traditionally, slam poets will gather together in throngs. Five random audience members are selected as judges and score each performance on a scale of one to ten. For each performance, the highest and lowest scores are dropped.

Slammers–Refers to a group of slam poets.

Spoken Word–Spoken word is a more correct term for slam poetry. It is words that were written to be spoken, often employing a meter or a scheme.

Stage Name–This is the slam poet’s version of a pen name. It is his or her character, someone he or she transforms into on stage. Many stage names are chosen to reflect the attitude or the purpose a poet has on stage.

Works Cited

Harrington, Tom. “FAQ: History of Visual Applause for the Deaf.” Gallaudet University. Gallaudet University Library, n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2012. <http://www.gallaudet.edu/library/research_help/research_help/frequently_asked_questions/cultural_social_medical/history_of_visual_applause_for_the_deaf.html>