The following guest post from Robert R. Sachs, Partner at Fenwick & West LLP, first appeared on the Bilski Blog, and it is reposted here with permission.

By Robert R. Sachs

July invokes images of hot days, cool nights, and fireworks. When it comes to #Alicestorm, the fireworks are happening in the courts, with the Federal Circuit lighting up the sky.

July invokes images of hot days, cool nights, and fireworks. When it comes to #Alicestorm, the fireworks are happening in the courts, with the Federal Circuit lighting up the sky.

In just the first ten days of July, there have been twelve decisions on patent eligibility—more decisions in the first ten days of any month since the dawn of time. At this pace, we could see some twenty to thirty decisions this month. #AliceStorm is accelerating.

Here are the numbers by motion type:

Here are the numbers for all the courts, by tribunal:

Finally, here’s a summary of the number of Section 101 decisions by the various judges on the Federal Circuit since Alice:

I leave the interpretation of this graph as an exercise for the reader.

Versata: The Federal Circuit is Large and In Charge

While the indices are steady, the recent decisions are very interesting. Most importantly, there have been two Federal Circuit decisions in July, Versata Development Group v. SAP Am., Inc. and Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Capital One Bank (USA), both of which found the patents in suit ineligible. Today, I’ll focus on Versata.

Versata was a closely watched appeal since it was the first appeal to the Federal Circuit of a Covered Business Methods review. The Court covered a lot of ground including 1) whether it could review PTAB’s determination that Versata’s patent was eligible for CBM review, 2) what is the meaning of “covered business method patent,” including whether USPTO’s definitions of a “financial product or service” and “technological invention” were correct, 3) what is the appropriate standard for claim construction, broadest reasonable interpretation or one correct construction, and 4) an evaluation of the merits. Briefly, the court decided:

- The Court can review PTAB final decisions, even when they touch upon the same legal issues that lead to the institution decision (which the Federal Circuit does not have authority to review), including whether a patent qualifies as a covered business method patent;

- The USPTO’s definitions of covered business method patent (which simply copies the statutory language without any definition at all) are just fine.

- PTAB can use broadest reasonable construction; and

- Versata’s patent is for a financial service, not a technological invention and is an ineligible abstract idea.

I’m not going to do an extensive analysis of the Federal Circuit’s handling of all these issues. Essentially, the Federal Circuit is saying: PTAB, keep up the good work of invalidating patents, but just remember, we’re still in charge. Instead, I’m going just to highlight some of the issues in the Court’s reasoning regarding the definitions of a covered business method patent.

As background, Versata’s patent is a way of determining prices where you have a very complex collection of products types and business groups, all overlapping and intersecting. Consider a company like General Motors with dozens of divisions and subsidiaries, hundreds of cars, and millions of parts. The problem is that conventional systems use multiple database tables to track and compute prices, requiring significant storage and reducing run-time performance. In a nutshell, Versata used hierarchical data structures representing product and business organizational hierarchies to store and compute product prices. By using hierarchical data structures, Versata’s invention saved memory and resulted in faster run-time performance than existing approaches.

What Is a Financial Product or Service?

Section 18(d)(1) of the statute that authorizes the CBM review states that a covered business method patent is:

a patent that claims a method or corresponding apparatus for performing data processing or other operations used in the practice, administration, or management of a financial product or service, except that the term does not include patents for technological inventions

The question is what is a financial product or service. The Court adopted the USPTO’s parsing of the phrase into financial and product or service. In doing so, the Court adopted PTAB’s incorrect grammatical parsing of the statute, which looked at the definition of financial apart from products and services. According to PTAB, “The term financial is an adjective that simply means relating to monetary matters.”

Running with this analysis the court concludes:

We agree with the USPTO that, as a matter of statutory construction, the definition of “covered business method patent” is not limited to products and services of only the financial industry, or to patents owned by or directly affecting the activities of financial institutions such as banks and brokerage houses. The plain text of the statutory definition contained in § 18(d)(1)— “performing . . . operations used in the practice, administration, or management of a financial product or service”— on its face covers a wide range of finance-related activities. The statutory definition makes no reference to financial institutions as such, and does not limit itself only to those institutions.

To limit the definition as Versata argues would require reading limitations into the statute that are not there.

This analysis is incorrect. The phrase financial product or service is not just the adjective financial modifying the nouns products and services—it’s not like sweet pastries and pies or funny songs and videos or complex issues and problems. Rather, financial product and financial service are open compound nouns, like high school, cell phone, and half sister. The meaning of these nouns is not determined by looking at the meaning of the individual words; the entire noun has its own meaning. When you attended high school, you did not go to a school that was “of great vertical extent”; when you speak on your cell phone you’re not talking on a telephone made of “the smallest structural and functional unit of an organism.” And when you offer to introduce me to your half sister, I don’t ask “Left or right?”

The term financial product means something specific and different from the simple combination of financial and product. It’s important to remember that the Covered Business Method program was pushed by three of the largest financial lobbying groups: the Financial Services Roundtable, the Independent Community of Banks of America, and the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. In the financial industry, financial products and services has a specific meaning.

Consider the following definitions of financial product:

a product that is connected with the way in which you manage and use your money, such as a bank account, a credit card, insurance, etc.

Cambridge Dictionary of Business EnglishFinancial products refer to instruments that help you save, invest, get insurance or get a mortgage. These are issued by various banks, financial institutions, stock brokerages, insurance providers, credit card agencies and government sponsored entities. Financial products are categorised in terms of their type or underlying asset class, volatility, risk and return.

EconomyWatch

Better yet, look at the U.S. Treasury’s definition:

The overarching definition of financial product will focus on the key attributes of, and functions performed by, financial products. A financial product will be defined as:

A facility or arrangement through which a person does one or more of the following:

— Makes a financial investment;

— Manages a financial risk;

— Obtains credit; or

— Obtains or receives a means of payment.The facility or arrangement may be provided by means of a contract or agreement or a number of contracts or agreements.

The term financial services is equally specific

Financial services are the economic services provided by the finance industry, which encompasses a broad range of businesses that manage money, including credit unions, banks, credit card companies, insurance companies, accountancy companies, consumer finance companies, stock brokerages, investment funds, real estate funds and some government sponsored enterprises.

Wikipedia, “Financial services”Financial Services is a term used to refer to the services provided by the finance market. Financial Services is also the term used to describe organizations that deal with the management of money. Examples are the Banks, investment banks, insurance companies, credit card companies and stock brokerages.

Streetdictionary.com, “What exactly does financial services mean?”

The USPTO and the Federal Circuit ignored these definitions of financial products and services as used by the very industries that sought protection from abusive business methods patents. The Court even notes that “It is often said, whether accurate or not, that Congress is presumed to know the background against which it is legislating.” Indeed, it did here, but the Court simply chooses to discount both that background and correct English language usage.

The Court further argues that the statutory definition makes no reference to financial institutions as such, implying that Congress did not intend to limit financial products and services to the financial services industries. To riff off the logical fallacy—evidence of an absence is not the absence of evidence. There was no need to mention explicitly the financial industry in the statute because the industry context is built into the terms themselves. Contrary to the Court’s final statement, the limitations are already in “the plain text of the statute.”

In short, looking up the Random House definition of the adjective financial apart from financial products and services is like extracting greasy from spoon and concluding that a greasy spoon is an oily small, shallow oval or round bowl on a long handle.

Whether you are talking business or busing tables, you must interpret words according to the relevant context, the relevant grammar, and the relevant dictionary.

Deference to the USPTO’s Expertise: Only Sometimes

In concluding its analysis of the meaning of a covered business method patent, the Court relies on a deference argument. In its final paragraph regarding the propriety of USPTO’s definition of financial product and services, the Court says:

Furthermore, the expertise of the USPTO entitles the agency to substantial deference in how it defines its mission.

The overall mission of the USPTO is to issue patents for inventions. The Ninth Circuit made a similar observation about the Copyright Office. In Garcia v. Google, the Copyright Office refused to register Garcia’s five-second appearance in a film. The Ninth Circuit noted “We credit this expert opinion of the Copyright Office—the office charged with administration and enforcement of the copyright laws and registration.” And thus the Ninth Circuit found it appropriate to defer to the office’s expertise in deciding copyrightable subject matter. The parallel could not be more perfect: the USPTO is the office charged with the administration and enforcement of the patent laws and registration. Likewise, the courts should defer to its expertise as well.

Here, when the USPTO comes up with a definition of technology in its interpretation of Section 18(d)(1) of the patent statute–a very small part of its mission–the Federal Circuit says that the Office is due substantial deference. Yet, when the Office comes up with a definition of Section 101–the section of the statute most fundamental to its mission–and when an examiner implements that definition and determines that a particular claim satisfies Section 101, that definition and that decision is given no deference at all.

Thus, I find it rather inconsistent of the Court to be deferential the USPTO’s definition of technology in a very narrow context, but entirely dismissive of the USPTO’s historical expertise in identifying patent eligible subject matter. When it comes to patents, the USPTO is like Rodney Dangerfield: it gets no respect.

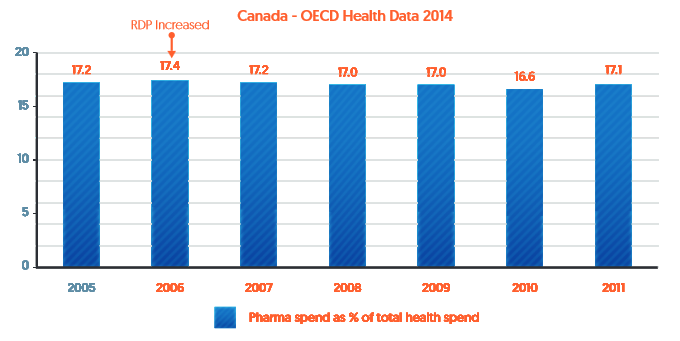

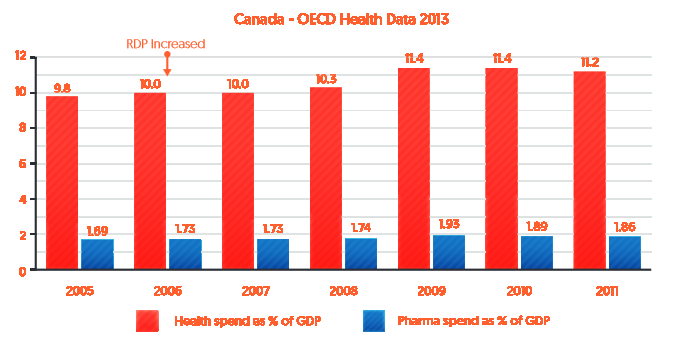

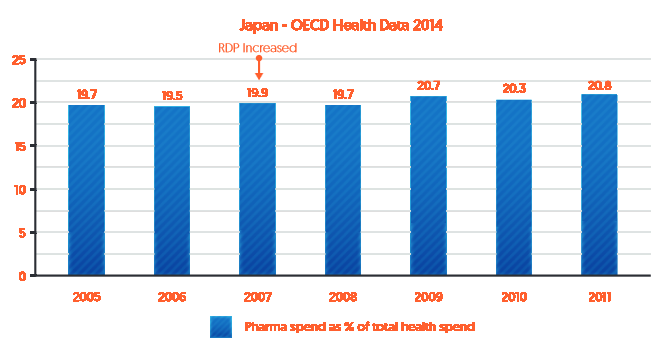

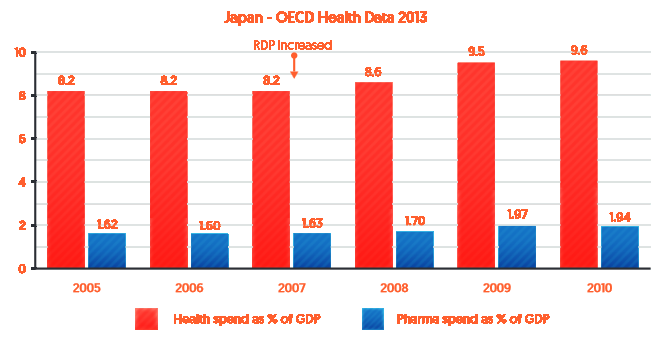

In the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations, the U.S. and Japan have proposed that TPP partners increase their period of regulatory data protection (RDP) for biologic medicines to align with practice in other countries. These proposals have been strongly opposed by a number of academics, who claim that such a move would significantly increase public spending on medicines, thereby potentially limiting access.

In the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations, the U.S. and Japan have proposed that TPP partners increase their period of regulatory data protection (RDP) for biologic medicines to align with practice in other countries. These proposals have been strongly opposed by a number of academics, who claim that such a move would significantly increase public spending on medicines, thereby potentially limiting access.

In

In