This post is one of a series in the #Innovate4Health policy research initiative.

Needlesticks are not just the fear of 4-year-olds receiving their vaccinations; they are also the source of blood-borne infections afflicting millions of healthcare practitioners. When a conventional needle is left exposed after use on a patient, it can accidentally stick another person, such as a healthcare worker. The accidental needlestick can infect that person if the patient had any blood-borne diseases. Recent estimates place the number of needlestick injuries in the United States at more than 300,000 per year, with infection by HIV or Hepatitis as possible consequences.

Needlesticks are not just the fear of 4-year-olds receiving their vaccinations; they are also the source of blood-borne infections afflicting millions of healthcare practitioners. When a conventional needle is left exposed after use on a patient, it can accidentally stick another person, such as a healthcare worker. The accidental needlestick can infect that person if the patient had any blood-borne diseases. Recent estimates place the number of needlestick injuries in the United States at more than 300,000 per year, with infection by HIV or Hepatitis as possible consequences.

The spring-retractable syringe, VanishPoint, was created to prevent needlestick injuries and ameliorate other unsafe injection practices.

Worldwide, the problem from needle injuries is even greater. The risks from needlestick injuries can increase with other unsafe injection practices, such as needle reuse and improper medical waste collection. These practices are more likely to occur in developing countries. The consequences of these unsafe injection practices include 21 million hepatitis B infections per year and 41% of new cases of hepatitis C.

The conventional syringe leaves the needle exposed after the injection is complete. Until a healthcare worked places the syringe in a specially-designed plastic garbage container, it remains exposed and capable of harming anyone nearby. Unfortunately, over 1.8 billion conventional syringes are sold each year in the United States. These outdated syringes account for more than half of needlestick injuries.

Thomas J. Shaw, founder of Retractable Technologies, created a technological solution to the problem after seeing a television report of a doctor who contracted HIV from an accidental needlestick. He designed a single use spring-loaded syringe that immediately pulls the needle back inside the just-used syringe. Thus, the needle is automatically covered and incapable of harming anyone.

Thomas J. Shaw, founder of Retractable Technologies, created a technological solution to the problem after seeing a television report of a doctor who contracted HIV from an accidental needlestick. He designed a single use spring-loaded syringe that immediately pulls the needle back inside the just-used syringe. Thus, the needle is automatically covered and incapable of harming anyone.

The basics of how the syringe works are simple enough to explain. The needle is engaged for use when the package is opened. A nurse or other practitioner fills the syringe normally. However, when the plunger is fully depressed to inject the patient, a spring pulls the needle back into the body of the syringe. Before the nurse has moved the syringe away from the patient, the needle is already covered and incapable of causing injury.

Despite the simple concept, designing a functional and usable product took ingenuity and persistence. Shaw purchased pigs feet from a local butcher to test his designs in his workshop. In the classic mode of biomedical innovators including Jonas Salk (inventor of the polio vaccine), he first tested his device on himself.

From these initial tests, Shaw founded Retractable Technologies, and the value of his innovation was immediately recognized. He received awards from the National Institute for Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health to further develop his work and eventually commercialize it. Congressional representatives touted the important advances of this small business. The final product, the VanishPoint syringe, embodies his innovation.

From these initial tests, Shaw founded Retractable Technologies, and the value of his innovation was immediately recognized. He received awards from the National Institute for Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health to further develop his work and eventually commercialize it. Congressional representatives touted the important advances of this small business. The final product, the VanishPoint syringe, embodies his innovation.

The challenges faced by Shaw and Retractable Technologies in entering the medical device market have been extensively chronicled. The way hospitals purchase supplies such as syringes advantages large incumbent sellers and manufacturers over small startups such as Retractable Technologies. The story of Shaw’s disruption of the automatic safety syringe market was even turned into a feature-length movie.

Retractable Technologies confronted this challenge by relying on its patent portfolio. The patents covering the syringe included patents on the retractable needle design as well as tamperproof features that protect against intentional as well as accidental misuse. Large, established manufacturers could have easily copied Retractable Technologies’ designs from the published patents. However, these patents assured that Retractable Technologies could protect its innovation against invasion.

The value of the retractable syringe design has been important to advancing health care goals worldwide. The World Health Organization has recognized the value of the technology in Australia, China, Indonesia, and Gambia among others. According to the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations, African countries continued using auto-disable syringes after the completion of international aid programs because of the public health benefits. These benefits include not only the prevention of needlestick injuries, but preventing needle reuse, which had undermined other vaccine initiatives.

The value of the retractable syringe design has been important to advancing health care goals worldwide. The World Health Organization has recognized the value of the technology in Australia, China, Indonesia, and Gambia among others. According to the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations, African countries continued using auto-disable syringes after the completion of international aid programs because of the public health benefits. These benefits include not only the prevention of needlestick injuries, but preventing needle reuse, which had undermined other vaccine initiatives.

PATH, a non-profit organization devoted to health innovation, highlighted the introduction of VanishPoint syringes in Peru as an important step in advancing public health goals. In addition to preventing injuries in the clinic, PATH noted that the syringes increased safety in waste disposal, where some waste handlers had described needlestick injuries as “common.”

Prevention of needlestick injuries and infections has been a decades-long challenge for public health. From humble beginnings and the story of one infected doctor, Thomas Shaw’s invention shows how one innovator can revolutionize health care. Patents have given him protection in the U.S., but his innovation knows no borders.

*Images courtesy of Retractable Technologies

#Innovate4Health is a joint research project by the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property (CPIP) and the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF). This project highlights how intellectual property-driven innovation can address global health challenges. If you have questions, comments, or a suggestion for a story we should highlight, we’d love to hear from you. Please contact Devlin Hartline at jhartli2@gmu.edu.

The House Judiciary Committee today

The House Judiciary Committee today  Last August, I wrote about CloudFlare’s “

Last August, I wrote about CloudFlare’s “ It seems no matter how many times the mole gets whacked, it keeps popping back up. The latest incarnation of this problem is a recent

It seems no matter how many times the mole gets whacked, it keeps popping back up. The latest incarnation of this problem is a recent  On February 16, 2017, CPIP hosted a panel discussion,

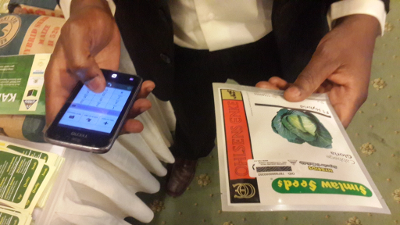

On February 16, 2017, CPIP hosted a panel discussion,  In 2007, Ghanaian tech entrepreneur

In 2007, Ghanaian tech entrepreneur  Through the combination of EarlySensor and Goldkeys, mPedigree’s innovative technology is facilitating the protection of both brand owners and consumers and ensuring that data collection and authentication mechanisms are leading to the safer distribution of medicines, cosmetics, seeds, and other essential products.

Through the combination of EarlySensor and Goldkeys, mPedigree’s innovative technology is facilitating the protection of both brand owners and consumers and ensuring that data collection and authentication mechanisms are leading to the safer distribution of medicines, cosmetics, seeds, and other essential products. By providing a dynamic link between consumers and manufacturers, mPedigree is making communications at the point of purchase routine and creating value for consumers, manufacturers, regulatory agencies, and sellers. A project ten years in the making, mPedigree is built on the recognition that protecting intellectual property—both mPedigree’s and its clients—can save lives.

By providing a dynamic link between consumers and manufacturers, mPedigree is making communications at the point of purchase routine and creating value for consumers, manufacturers, regulatory agencies, and sellers. A project ten years in the making, mPedigree is built on the recognition that protecting intellectual property—both mPedigree’s and its clients—can save lives. Awards season always seems to arrive with new stories about how piracy is affecting the film industry and the way we watch movies. Whether it’s a promotional screener that was stolen and uploaded to a torrent site, or the latest software that allows users to download or stream pirated content, the tales are reminders of the enduring problem of online copyright infringement.

Awards season always seems to arrive with new stories about how piracy is affecting the film industry and the way we watch movies. Whether it’s a promotional screener that was stolen and uploaded to a torrent site, or the latest software that allows users to download or stream pirated content, the tales are reminders of the enduring problem of online copyright infringement. One promising example of these new mobile diagnostic applications for eye care is the

One promising example of these new mobile diagnostic applications for eye care is the  How does PEEK work? An app and a clip-on adapter

How does PEEK work? An app and a clip-on adapter  On March 8, 2017, CPIP Scholars Adam Mossoff, Devlin Hartline, Chris Holman, Sean O’Connor, Kristen Osenga, & Mark Schultz joined an

On March 8, 2017, CPIP Scholars Adam Mossoff, Devlin Hartline, Chris Holman, Sean O’Connor, Kristen Osenga, & Mark Schultz joined an