Today, Representatives Steve Stivers (R-OH) and Bill Foster (D-IL) introduced the Support Technology & Research for Our Nation’s Growth and Economic Resilience (STRONGER) Patents Act of 2018. This important piece of legislation will protect our innovation economy by restoring stable and effective property rights for inventors. This legislation mirrors a bill already introduced in the Senate, which I have previously discussed.

Today, Representatives Steve Stivers (R-OH) and Bill Foster (D-IL) introduced the Support Technology & Research for Our Nation’s Growth and Economic Resilience (STRONGER) Patents Act of 2018. This important piece of legislation will protect our innovation economy by restoring stable and effective property rights for inventors. This legislation mirrors a bill already introduced in the Senate, which I have previously discussed.

The STRONGER Patents Act accomplishes three key goals to protect innovators. First, the Act will make substantial improvements to post-issuance proceedings in the USPTO to protect patent owners from administrative proceedings run amok. Second, it will confirm the status of patents as property rights, including restoring the ability of patent owners to obtain injunctions as a matter of course. Third, it will eliminate fee diversion from the USPTO, assuring that innovators are obtaining the quality services they are paying for.

First and foremost, the STRONGER Patents Act aims to restore balance to post-issuance review of patents administered by the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). The creation of the PTAB was a massive regulatory overreach to correct a perceived problem that could have been better addressed by providing more resources towards initial examination. While the USPTO has long been responsible for issuing patents after a detailed examination, it has recently taken on the role of killing patents the same USPTO previously issued. What the USPTO gives with the one hand, it takes with the other.

Data analyzing PTAB outcomes demonstrates just how dire the situation has become. Coordinated and repetitive challenges to patent validity have made it impossible for patent owners to ever feel confident in the value and enforceability of their property rights. In some cases, more than 20 petitions have been filed on a single patent. Although recent headway has been made to address this issue in the administrative context, it only listed factors to be used when evaluating serial petitions. A more complete statutory solution that prohibits serial petitions except in limited circumstances is necessary to fully protect innovators and provide certainty that these protections will continue.

The kill rate of patents by the PTAB is remarkable. In only 16% of final written decisions at the PTAB does the patent survive unscathed. The actual impact on patent owners is far worse. Disclaimer and settlement are alternate ways a patent owner can lose at the PTAB prior to a final written decision. Thus, the fact that only 4% of petitions result in a final written decision of patentability is more reflective of the burden patent owners faced when dragged into PTAB proceedings.

For these reasons, the PTAB has been known as a “death squad.” This sentiment has been expressed not only by those who are disturbed by the PTAB’s behavior, but also those—such as a former chief judge of the PTAB—who are perpetuating it. The list of specific patents that have been invalidated at the PTAB is mind-boggling, such as an advanced detector for detecting leaks in gas lines.

There are even examples where the PTAB has invalidated a patent that had previously been upheld by the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals. One recent examination further found that there have been at least 58 patents that were upheld in federal district courts that were invalidated in the PTAB on the same statutory grounds. The different results are not mere happenstance but are the result of strategic behavior by petitioners to strategically abuse the procedures of PTAB proceedings.

It has been well known that the procedures have been stacked against patent owners from day one. We and others have noted how broadly construing claims, multiple filings against the same patent by the same challengers, and the inability to amend claims, among other abuses, severely disadvantage patent owners in PTAB proceedings.

With the STRONGER Patents Act, these proceedings will move closer to a fair fight to truly examine patent validity. There are many aspects to this legislation that will improve the PTAB, such as:

- Harmonizing the claim construction standard with litigation, focusing on the “ordinary and customary meaning” instead of the broadest interpretation a bureaucrat can conceive. This will promote consistent results when patents are challenged, regardless of the forum, by assuring that a patent does not mean different things to different people. Sections 102(a) and 103(a).

- Confirming the presumption of validity of an issued patent will apply to the PTAB just as it does in litigation. This will allow patent owners to make investments with reasonable security in the validity of the patent. Sections 102(b) and 103(b).

- Adding a standing requirement, by permitting only those who are “charged with infringement” of the patent to challenge that patent. This will prevent the abusive and extortionate practice of challenging a patent to extract a settlement or short a company’s stock. Sections 102(c) and 103(c).

- Limiting abusive repetitive and serial challenges to a patent. This will prevent one of the most common abuses, by preventing multiple bites at the apple. Sections 102(d), (f) and 103(d), (f).

- Authorizing interlocutory review of institution decisions when “mere institution presents a risk of immediate, irreparable injury” to the patent owner as well as in other important circumstances. This change will allow early correction of important mistakes as well as provide for appellate review of issues that currently may evade correction. Sections 102(e) and 103(e).

- Prohibiting manipulation of the identification of the real-party-in-interest rules to evade estoppel or other procedural rules and providing for discovery to determine the real-party-in-interest. Because many procedural protections depend on identifying the real party-in-interest, this change will assure that determining who that real party is can occur in a fair manner. Sections 102(g) and 103(g).

- Giving priority to federal court determinations on the validity of a patent. Although discrepancies will be minimized by other changes in this Act, this section assures that the federal court determination will prevail. Sections 102(h) and 103(h).

- Improving the procedure for amending a challenged patent, including a new expedited examination pathway. This section goes further than Aqua Products, prescribing detailed procedures for adjudicating the patentability of proposed substitute claims and placing the burden of proof on the challenger. Sections 102(i) and 103(i).

- Prohibiting the same administrative patent judges from both determining whether a challenge is likely to succeed and whether the patent is invalid. This section will confirm the original design of the PTAB by assuring that the decision to institute and final decision are separate. Section 104.

- Aligning timing requirements for ex parte reexamination with inter partes review by prohibiting requests for reexamination more than one year after being sued for infringement. This section will prevent abuses from the multiple post-grant procedures available in the USPTO. Section 105.

Second, the STRONGER Patents Act will make other necessary corrections to allow patents to promote innovation. For example, as Section 101 of the Act confirms, patents are property rights and deserve the same remedies applicable to other kinds of property. In eBay v. MercExchange, the Supreme Court ignored this fundamental premise by holding that patent owners do not have the presumptive right to keep others from using their property. Section 106 of the STRONGER Patents Act will undo the disastrous eBay decision and confirm the importance of patents as property.

Third, the STRONGER Patents Act will once and for all eliminate USPTO fee diversion. Many people do not realize that the USPTO is funded entirely through user fees and that no taxpayer money goes to the office. Despite promises that the America Invents Act of 2011 would end fee diversion, the federal government continues to redirect USPTO funds to other government programs. This misguided tax on innovation is long overdue to be shut down.

Each of the steps in the STRONGER Patents Act will help bring balance back to our patent system. In addition to the major changes described above, there are also smaller changes that will be important to ensuring a vibrant and efficient patent system. CPIP co-founder Adam Mossoff testified to Congress about the harms being done to innovation through weakened patent protection. It is great news to now see Congress taking steps in the right direction.

Poor sanitation poses an ongoing threat to the health and well-being of people in the developing world. Severe health problems, death, and disease can be directly linked to unsafe hygiene practices that continue to plague many countries. A

Poor sanitation poses an ongoing threat to the health and well-being of people in the developing world. Severe health problems, death, and disease can be directly linked to unsafe hygiene practices that continue to plague many countries. A  In 2012, with

In 2012, with  Access to proper sanitation and clean water is vital for the

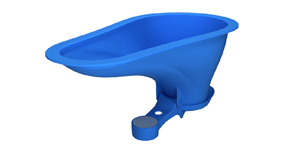

Access to proper sanitation and clean water is vital for the  Invented by Jim McHale, Daigo Ishiyama and Greg Gatarz, the

Invented by Jim McHale, Daigo Ishiyama and Greg Gatarz, the  Crucially, the design of the pan allows for potential variations according to local customs and demands, such as using the facilities by squatting or sitting or adapting to the shape of the pit for the latrine. The core concept around which the pan is based is the counterweighted “flapper” itself. The counterweight is specifically set so that the flap remains closed until the additional force of water – not just the waste itself – is poured into the pan. The pour-flush mechanic also creates a liquid seal, with a minimal amount of water remaining on top of the flap after use to help ensure prevention of transmission of insects or gases. This approach, utilizing a basic mechanism while leaving room for responsive adjustments in design, allows the SaTo pan to be adapted globally while maintaining a simple but effective means of providing basic health benefits.

Crucially, the design of the pan allows for potential variations according to local customs and demands, such as using the facilities by squatting or sitting or adapting to the shape of the pit for the latrine. The core concept around which the pan is based is the counterweighted “flapper” itself. The counterweight is specifically set so that the flap remains closed until the additional force of water – not just the waste itself – is poured into the pan. The pour-flush mechanic also creates a liquid seal, with a minimal amount of water remaining on top of the flap after use to help ensure prevention of transmission of insects or gases. This approach, utilizing a basic mechanism while leaving room for responsive adjustments in design, allows the SaTo pan to be adapted globally while maintaining a simple but effective means of providing basic health benefits. By Alex Summerton & Nick Churchill

By Alex Summerton & Nick Churchill One solution to these problems is to effectively move clinics to the patients through

One solution to these problems is to effectively move clinics to the patients through  Daktari (Swahili for “Doctor”) Diagnostics is working on the development of a point-of-care testing platform that meets the ASSURED standards. Daktari’s portable point-of-care platform,

Daktari (Swahili for “Doctor”) Diagnostics is working on the development of a point-of-care testing platform that meets the ASSURED standards. Daktari’s portable point-of-care platform,  Last week, a group of CPIP scholars filed an

Last week, a group of CPIP scholars filed an