Greetings from CPIP Executive Director Sean O’Connor

As we move into another month of stay-at-home here in the DMV—and perhaps some re-openings—we here at CPIP hope that you and yours are staying safe and healthy while we weather this crisis.

We continue to move forward, however. Our biggest news this month is the addition of Joshua Kresh as our new Deputy Director. Most recently an IP attorney at DLA Piper, he has worked at other major firms and is active in policy and new lawyer training with AIPLA and the Giles Rich Inn of Court. Joshua brings with him a patent-rich legal background, and he’ll be a valuable asset to the CPIP team and mission. We look forward to working with him and hope you wish him the best as he takes up this new role.

Like many other schools and organizations, Scalia Law School and CPIP have moved online for the time being—but that doesn’t mean we’ve stopped forging ahead and navigating new challenges. Because all George Mason University onsite events have been cancelled through August 8, we’ve moved our much-anticipated Music Law Conference back to September 10-11, 2020. We greatly appreciate the flexibility and understanding of every single person involved, not least our special guest and keynote speaker, Rosanne Cash. We hope you can still join us for the event in the fall—and, if you were unable to make the April dates, we hope this postponement works to your benefit!

CPIP’s main event this summer, the WIPO-CPIP Summer School on Intellectual Property for this coming June 8-19, 2020, has moved online as a virtual program via WebEx. CPIP primarily will serve participants in the Americas, although we’ll also be welcoming a number of attendees from other parts of the world who have opted to stay with the U.S.A. program.

As of March, I joined the Board of Directors for The Circle Foundation, an organization in the Republic of Korea that supports innovation and entrepreneurship to strengthen the start-up ecosystem. This new role brings CPIP and Scalia Law School into another level of connection with Mason Korea’s excellent in-country campus and activities.

In April, I was a virtual guest speaker for CPIP Co-Founder—and now University of Akron Goodyear Tire & Rubber Chair of Intellectual Property—Mark Schultz’s WebEx event, Copyright and Social Justice: How the “Blurred Lines” Case Brought Overdue Recognition for African American Artist. The talk was co-sponsored by the Black Law Students Association and the Intellectual Property and Technology Law Association. Also in April, I gave a virtual presentation to admitted Scalia Law prospective students on Cannabis: Creating a New Regulated Economy.

CPIP and our colleagues have remained productive over these past weeks, from rescheduling events to publishing timely pieces. My article Distinguishing Different Kinds of Property in Patents and Copyrights—based on an early presentation at CPIP’s Annual Fall Conference—was published in the George Mason Law Review, and my recent op-ed, Avoiding Another Great Depression Through a Developmentally Layered Reopening of the Economy, appeared in The Hill. I was interviewed on WBAL for this piece as well. Finally, CPIP along with many other organizations from around the world signed onto an open letter to WIPO’s Director-General for World IP Day.

This past month and a half have undoubtedly been difficult. At CPIP, our thoughts go out especially to all creators and innovators who are facing new challenges as they strive to protect their livelihoods and intellectual property in this difficult time. We truly hope this May brings improvements, both locally and globally. Stay well, safe, and sane.

CPIP Welcomes Joshua Kresh as Deputy Director

CPIP is proud to welcome Joshua Kresh to our leadership team! As Deputy Director, Joshua will report to CPIP Executive Director Sean O’Connor while managing and participating in CPIP’s day-to-day operations. Joshua will oversee CPIP’s academic research, policy, and fundraising efforts, working as well on planning and executing CPIP events such as conferences, meetings, fellowships, and roundtables. Joshua will also consult with Professor O’Connor and the other faculty directors to develop CPIP’s long-term academic and policy plans.

Before joining CPIP as Deputy Director, Joshua was an Associate with DLA Piper in Washington, D.C., where he practiced patent litigation. He received his law degree with honors from The George Washington University Law School, and he holds master’s and bachelor’s degrees in computer science from Brandeis University. Joshua is the Chair of AIPLA’s New Lawyers Committee and Co-Mentoring Chair of the Giles Rich American Inn of Court, and he is a registered patent attorney with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

To read the rest of our announcement, please click here.

Music Law Conference with Rosanne Cash Moved to September 10-11, 2020

We are excited to announce that the music law conference, The Evolving Music Ecosystem, which will be held at Antonin Scalia Law School in Arlington, Virginia, has now been moved to September 10-11, 2020. The keynote address will be given by Rosanne Cash, and it features two days of panel presentations from leading experts.

This unique conference continues a dialogue on the music ecosystem begun by CPIP Executive Director Sean O’Connor while at the University of Washington School of Law in Seattle. In its inaugural year in the D.C. area, the conference aims to bring together musicians, music fans, lawyers, artist advocates, business leaders, government policymakers, and anyone interested in supporting thriving music ecosystems in the U.S. and beyond.

For more information, and to register, please click here.

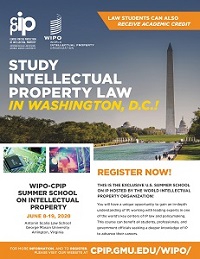

Registration Open for WIPO-CPIP Summer School on IP on June 8-19, 2020

CPIP has again partnered with the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) to host the third iteration of the WIPO-CPIP Summer School on Intellectual Property from Antonin Scalia Law School in Arlington, Virginia, on June 8-19, 2020. Registration is now open, and we recommend that participants apply early, as we expect the program to be full. In order to accommodate the global response to COVID-19, we have moved the course online this year.

The course provides a unique opportunity for students, professionals, and government officials to work with leading experts to gain a deeper knowledge of IP to advance their careers. The course consists of lectures, case studies, simulation exercises, group discussions, and panel discussions on selected IP topics, with an orientation towards the interface between IP and other disciplines. U.S. law students can receive 3 hours of academic credit from Scalia Law!

For more information, and to register, please click here.

Spotlight on Scholarship

Sean M. O’Connor, Distinguishing Different Kinds of Property in Patents and Copyrights, 27 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 205 (2019)

In this paper from our Annual Fall Conference, CPIP Executive Director Sean O’Connor explores the different meanings of “property” with respect to patents and copyrights. Prof. O’Connor explains that, contrary to the current conventional wisdom, the purpose of protection in early modern Europe was to incentivize public disclosure and commercialization, not private creation. To demonstrate this, he traverses the evolution of different kinds of property, including private knowledge, ad hoc grants of rights, rights in goods that embody intellectual property, and contractual assignments or licenses. Prof. O’Connor then describes how confusion over these different kinds of property has lead people to talk past each other in intellectual property debates, and he argues that a more nuanced understanding of the various property interests at stake might enable more constructive engagements going forward.

Charles Delmotte, The Case Against Tax Subsidies in Innovation Policy, 48 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. ___ (forthcoming)

In this paper from our Thomas Edison Innovation Fellowship, Charles Delmotte of NYU Law assesses the proposal for replacing intellectual property rights with tax subsidies for research and development (R&D) firms. Dr. Delmotte explains that innovation scholarship neglects economic insights on efficiencies, such as how information problems prevent the efficient operationalization of tax subsidies since innovation outcomes turn on unpredictable market processes that cannot be steered in advance. Turning to public choice theory, Dr. Delmotte points out that tax subsidies are particularly susceptible to diversion by the rent-seeking behavior of the politically affluent, and relying on economic realism, he argues that the best way to promote innovation is by securing stable intellectual property rights that undergird the background institutions that facilitate competition and entrepreneurship.

Activities, News, & Events

In a new CPIP policy brief entitled The End of Patent Groupthink, CPIP Senior Fellow for Innovation Policy Jonathan Barnett highlights some cracks that have emerged in the recent policy consensus that the U.S. patent system is “broken” and it is necessary to “fix” it. Policymakers have long operated on the basis of mostly unquestioned assumptions about the supposed explosion of low quality patents and the concomitant patent litigation that purportedly threaten the foundation of the innovation ecosystem. These assumptions have led to real-world policy actions that have weakened patent rights. But as Prof. Barnett discusses in the policy brief, that “groupthink” is now eroding as empirical evidence shows that the rhetoric doesn’t quite match up to the reality. This has translated into incremental but significant movements away from the patent-skeptical trajectory that has prevailed at the Supreme Court, the USPTO, and the federal antitrust agencies.

We have several new posts on the CPIP blog, including the first installment of our new series on recent copyright law developments. In a post entitled Copyright Notebook: Observations on Copyright in the Time of COVID-19, CPIP Director of Copyright Research and Policy Sandra Aistars discusses several current copyright cases and issues, including how artists, authors, and copyright industries have taken unprecedented steps to bring enjoyment to our circumscribed lives. We published a similarly hopeful piece entitled IP Industries Step Up in This Time of Crisis on how bio-pharma industries and scientific publishers have made crucial information and materials available when they are needed the most. CPIP Director of Communications Devlin Hartline published a piece entitled Supreme Court Paves Way for Revoking State Sovereign Immunity for Copyright Infringement that looks at the Supreme Court’s decision in Allen v. Cooper. And CPIP Senior Fellow for Life Sciences Erika Lietzan published a piece entitled The Tradeoffs Involved in New Drug Approval, Expanded Access, and Right to Try on the various issues with approving new medicines.

CPIP Senior Scholar Kristen Osenga joined Professors Greg Dolin and Irina Manta in filing an amicus brief urging the Supreme Court to grant certiorari in Celgene v. Peter. The issue on appeal is one that was left unresolved in Oil States v. Greene’s Energy, namely, whether retrospective applications of inter partes review (IPR) proceedings under the 2011 American Invents Act are unconstitutional takings. The brief argues that, for several reasons, the Federal Circuit below reached the wrong conclusion in holding that they are not unconstitutional. First, IPRs are significantly different than ex parte and inter partes reexaminations, since patentees are not free to amend claims in order to resolve claim scope ambiguities. Second, empirical research shows that the economic impact of such IPRs is to devalue patents and chill investment. Finally, the cases relied on by the Federal Circuit to support its conclusion are inapposite or outdated. The amicus brief was featured in a recent article at IPWatchdog entitled Amici Urge Supreme Court to Grant Celgene’s Petition on Constitutionality of Retroactive IPRs.

CPIP is proud to welcome

CPIP is proud to welcome  The Indomitable Spirit of Artists

The Indomitable Spirit of Artists The global COVID-19 pandemic has challenged multiple aspects of modern society in a short time. Health and public safety, education, commerce, research, arts, and even basic government functions have had to change dramatically in the space of a couple months. Some good news in all this is the response of many companies in the intellectual property (IP) industries: they are stepping up to make sure crucial information and materials are available to speed research and development (R&D) towards vaccines, therapeutics, and medical devices. This blog post gives a sampling of the current initiatives facilitating the best innovative work the world has to offer.

The global COVID-19 pandemic has challenged multiple aspects of modern society in a short time. Health and public safety, education, commerce, research, arts, and even basic government functions have had to change dramatically in the space of a couple months. Some good news in all this is the response of many companies in the intellectual property (IP) industries: they are stepping up to make sure crucial information and materials are available to speed research and development (R&D) towards vaccines, therapeutics, and medical devices. This blog post gives a sampling of the current initiatives facilitating the best innovative work the world has to offer. In a new CPIP policy brief entitled

In a new CPIP policy brief entitled