It is common today to hear that it’s simply impossible to search a field of technology to determine whether patents are valid or if there’s even freedom to operate at all. We hear this complaint about the lack of transparency in finding “prior art” in both the patent application process and about existing patents.

It is common today to hear that it’s simply impossible to search a field of technology to determine whether patents are valid or if there’s even freedom to operate at all. We hear this complaint about the lack of transparency in finding “prior art” in both the patent application process and about existing patents.

The voices have grown so loud that Michelle K. Lee, Director of the Patent Office, has made it a cornerstone of her administration to bring greater transparency to the operations of the USPTO. She laments the “simple fact” that “a lot of material that could help examiners is not readily available, because the organizations retaining that material haven’t realized that making it public would be beneficial.” And she’s been implementing new programs to provide “easy access by patent examiners to prior art” as a “tool to help build a better IP system.”

We hear this complaint about transparency most often from certain segments of the high-tech industry as part of their policy message that the “patent system is broken.” One such prominent tech company is search giant Google. In formal comments submitted to the USPTO, for instance, Google asserts that a fundamental problem undermining the quality of software patents is that a “significant amount of software-related prior art does not exist in common databases of issued patents and published academic literature.” To remedy the situation, Google has encouraged the Patent Office to make use of “third party search tools,” including its own powerful search engines, to locate this prior art.

Google is not shy about why it wants more transparency with prior art. In a 2013 blog post, Google Senior Patent Counsel Suzanne Michel condemned so-called “patent trolls” and argued that the “PTO should improve patent quality” in order to “end the growing troll problem.” In comments from 2014, three Google lawyers told the Patent Office that “poor quality software patents have driven a litigation boom that harms innovation” and that making “software-related prior art accessible” will “make examination in the Office more robust to ensure that valid claims issue.” In comments submitted last May, Michel even proposed that the Patent Office use Google’s own patent search engines for “streamlining searches for relevant prior art” in order to enhance patent quality.

Given Google’s stance on the importance of broadly available prior art to help weed out vague patents and neuter the “trolls” that wield them, you’d think that Google would share the same devotion to transparency when it comes to its own patent applications. But it does not. Google has not mentioned in its formal comments and in its public statements that even using its own search engine would fail to disclose a substantial majority of its own patent applications. Unlike the other top-ten patent recipients in the U.S., including many other tech companies, Google keeps most of its own patent applications secret. It does this while at the same time publicly decrying the lack of transparency in the patent system.

The reality is that Google has a patent transparency problem. Not only does Google not allow many of its patent applications to be published early or even after eighteen months, which is the default rule, Google specifically requests that many of its patent applications never be published at all. So while Google says it wants patent applications from around the world to be searchable at the click of a mouse, this apparently does not include its own applications. The numbers here are startling and thus deserve to be made public—in the name of true transparency—for the first time.

Public Disclosure of Patent Applications

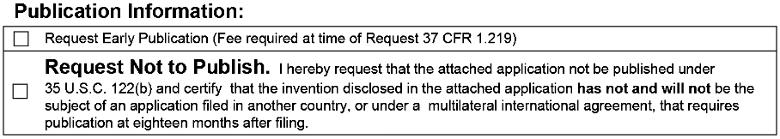

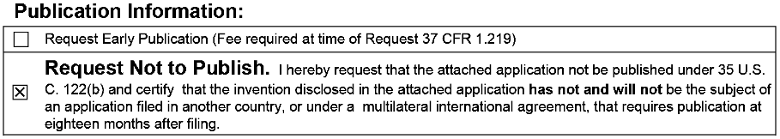

Beginning with the American Inventors Protection Act of 1999 (AIPA), the default rule has been that a patent application is published eighteen months after its filing date. The eighteen-month disclosure of the patent application will occur unless an applicant files a formal request that the application not be published at all. An applicant also has the option to obtain early publication in exchange for a fee. Before the AIPA, an application would only be made public if and when the patent was eventually granted. This allowed an applicant to keep her invention a trade secret in case the application was later abandoned or rejected.

The publication of patent applications provides two benefits to the innovation industries, especially given that the waiting time between filing of an application and issuance of the patent or a final rejection by an examiner can take years. First, earlier publication of applications provides notice to third parties that a patent may cover a technology they are considering adopting in their own commercial activities. Second, publication of patent applications expands the field of publicly-available prior art, which can be used to invalidate either other patent applications or already-issued patents themselves. Both of these goals produce better-quality patents and an efficiently-functioning innovation economy.

Separate from the legal mandate to publish patent applications, Google has devoted its own resources to creating greater public access to patents and patent applications. From its Google Patent Search in 2006 and its Prior Art Finder in 2012 to its current Google Patents, Google has parlayed its search expertise into making it simple to find prior art from around the world. Google Patents now includes patent applications “from the USPTO, EPO, JPO, SIPO, WIPO, DPMA, and CIPO,” even translating them into English. It’s this search capability that Google has been encouraging the Patent Office to utilize in the quest to make relevant prior art more accessible.

Given Google’s commitment to patent transparency, one might expect that Google would at least be content to allow default publication of its own applications under the AIPA’s eighteen-month default rule. Perhaps, one might think, Google would even opt for early publication. However, neither appears to be the case; Google instead is a frequent user of the nonpublication option.

Google’s Secrecy vs. Other Top-Ten Patent Recipients

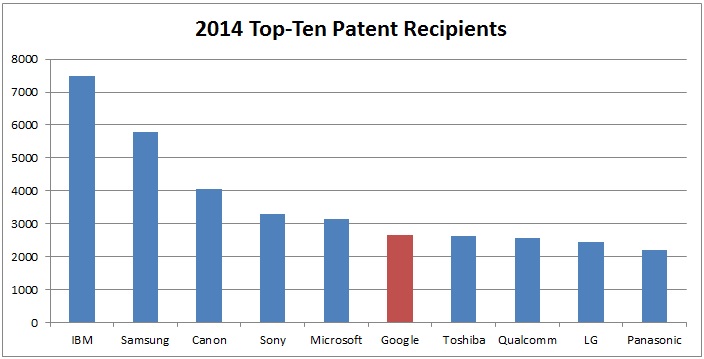

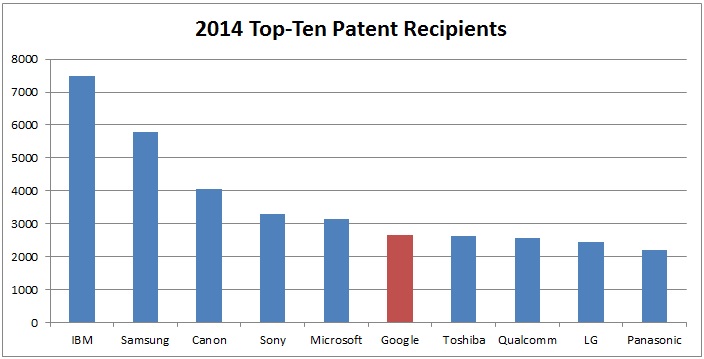

After hearing anecdotal reports indicating that Google was frequently using its option under the AIPA to avoid publishing its patent applications, we decided to investigate further. We looked at the patents Google received in 2014 to see what proportion of its applications was subject to nonpublication requests. To provide context, we also looked at how Google compared to the other top-ten patent recipients in this regard. The results are startling.

Unfortunately, there’s no simple way to tell if a nonpublication request was made when a patent application was filed using the USPTO’s online databases—nonpublication requests are not an available search field. The same appears to be true of subscription databases. The searches therefore have to be done manually, digging through the USPTO’s Public PAIR database to find the application (known in patent parlance as the “file wrapper”) for each individual patent that includes the individual application documents. Those interested in doing this will find startling numbers of patent applications kept secret by Google, both in terms of absolute numbers but also as compared to the other top-ten recipients of U.S. patents.

By way of example as to what one needs to look for, take the last three patents issued to Google in 2014: D720,389; 8,925,106; and 8,924,993.

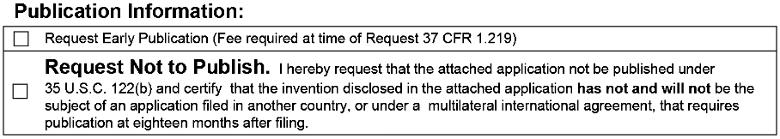

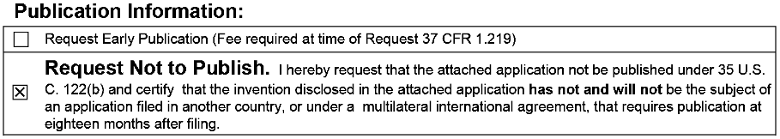

For the first patent, the application was filed on December 13, 2013, and according to the application data sheet, no request was made to either publish it early or not publish it at all:

Since no such request was made, the application would normally be published eighteen months later or upon issuance of the patent. Indeed, that is what happened in due course—this patent issued just over one year after the application was filed, as it was concurrently published and issued in December of 2014.

For the second patent in our small set of examples, the application was filed on April 20, 2012. In this case, Google requested nonpublication by including a letter requesting that the application not be published:

Google thus opted out of the default eighteen-month publication rule, and the application was not published until the patent issued in December of 2014, some twenty months later.

Finally, for the third patent, the application was filed on November 10, 2011, and the application data sheet shows that Google requested the application not be published:

Google here again opted out of the default publication rule, and the application was not published until the patent issued in December of 2014—more than three years after the application was filed.

We applied this methodology to a random sample of 100 patents granted to each of the top-ten patent recipients in 2014.

In 2014, Google was one of the top-ten patent recipients, coming in sixth place with 2,649 issued patents:

SOURCES: USPTO PatentsView Database & USPTO Patent Full-Text and Image Database

We randomly sampled 100 patents for each of the top-ten patent recipients for 2014. We reviewed the file wrapper for each to determine the proportion of nonpublication requests in each sample.

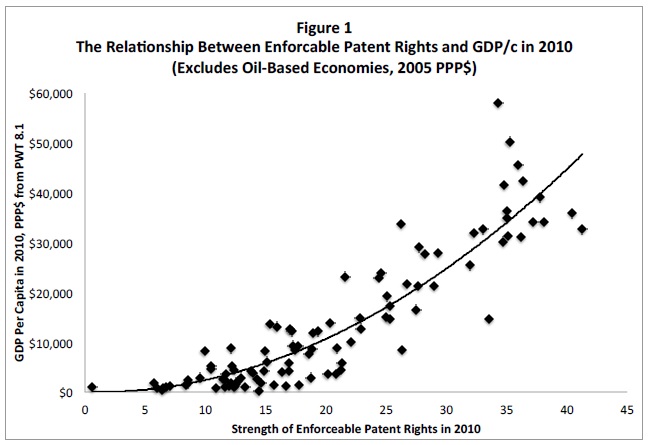

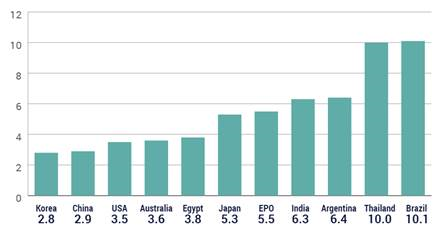

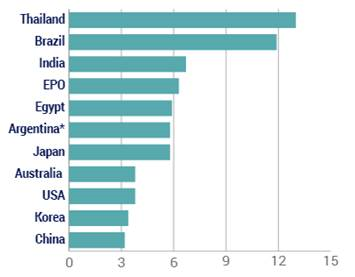

Our results revealed that Google is an extreme outlier among top-ten patent recipients with respect to nonpublication requests. Eight of the top-ten patent recipients made zero requests for nonpublication, permitting their patent applications to be published at the eighteen-month deadline. The eighth-ranking patent recipient, Qualcomm, requested that one application not be published. By contrast, Google formally requested that 80 out of 100—a full 80%—of its applications not be published.

The following chart shows these results:

SOURCE: USPTO Public PAIR Database

Conclusion

Based on this result, Google deliberately chooses to keep a vast majority of its patent applications secret (at least it did so in 2014). This secrecy policy for its own patent applications is startling given both Google’s public declarations of the importance of publication of all prior art and its policy advocacy based on this position. It is even more startling when seen in stark contrast to the entirely different policies of the other nine top patent recipients for 2014.

It is possible that 2014 was merely an anomaly, and that patent application data from other years would show a different result. We plan to investigate further. So, stay tuned. But for whatever reason, it appears that Google doesn’t want the majority of its patent applications to be published unless and until its patents finally issue. This preference for secrecy stands in contrast to Google’s own words and official actions.

As one of the top patent recipients in the U.S., you’d think Google would want its applications to be published as quickly as possible. The other top recipients of U.S. patents in 2014 certainly adopt this policy, furthering the goal of the patent system in publicly disclosing new technological innovation as quickly as possible. The fact that Google does otherwise speaks volumes.

By

By

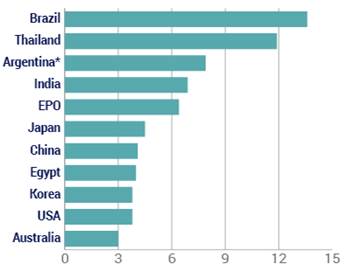

Why are some of the biggest fights about patent policy almost pointless in some places? Because in many countries, including some of the world’s most important emerging economies, it takes so long to get patents that the rights have little meaning.

Why are some of the biggest fights about patent policy almost pointless in some places? Because in many countries, including some of the world’s most important emerging economies, it takes so long to get patents that the rights have little meaning.

Earlier this month, CPIP Senior Scholar Adam Mossoff penned an

Earlier this month, CPIP Senior Scholar Adam Mossoff penned an  Following the Supreme Court’s four decisions on patent eligibility for inventions under

Following the Supreme Court’s four decisions on patent eligibility for inventions under