Last week, CPIP released an important new policy brief, The Critical Role of Patents in the Development, Commercialization, and Utilization of Innovative Genetic Diagnostic Tests, by Professor Chris Holman. Professor Holman explains the important role that patents play not only in attracting the capital investment needed to bring genetic tests to market, but also in incentivizing companies to invest in educating patients and their doctors about new tests and in facilitating insurance reimbursements for new tests. Professor Holman addresses the common mistaken assumption that patents negatively impact patient access to genetic diagnostic testing, concluding instead that patent protection is a critical spur for the innovation and commercialization of next-generation genetic diagnostic tests.

The full document (including endnotes) is available here, and we’ve also included the text (without endnotes) below.

The Critical Role of Patents in the Development, Commercialization, and Utilization of Innovative Genetic Diagnostic Tests

Christopher M. Holman

Genetic diagnostic testing is an increasingly high-profile subject in the minds of the public, academia, and policymakers. This increased attention was prompted in part by highly publicized events such as Angelina Jolie’s decision to undergo a preemptive double mastectomy based on the results of a genetic diagnostic test, followed shortly thereafter by a U.S. Supreme Court decision invalidating patent claims held by the company (Myriad Genetics) that developed the test used by Ms. Jolie. Although traditionally viewed as a relatively unglamorous sector of the healthcare market (accounting for less than 2% of total health care spending), genetic analysis and other innovative molecular diagnostics seem poised to become “a powerful element of the healthcare value chain,” playing an increasingly important role in the prediction, detection, and treatment of disease. “Personalized medicine,” a new term that refers to the pairing of a molecular diagnostic test with a patient-specific course of pharmaceutical treatment, represents a particularly promising avenue through which molecular diagnostics might improve therapeutic outcomes while containing healthcare costs.

Those involved in the development and commercialization of innovative molecular diagnostics stress the important role of effective intellectual property rights in attracting the substantial capital investment required to bring these products to market. Influential voices outside the innovation community, however, have argued strongly against patent protection for molecular diagnostics, claiming that such patents are overly broad, reduce patient access, and inhibit research that might otherwise lead to new and improved diagnostic tests. Most of these critics would acknowledge that strong patent protection is appropriate, and indeed critical, for the development of innovative drugs, in view of the huge cost of developing drugs and securing FDA marketing approval. They argue, however, that the same considerations do not apply to diagnostic tests. Unfortunately, their argument is based largely on the outdated and now-incorrect belief that diagnostic tests are developed by publicly-funded academics who are primarily motivated by non-patent incentives, and that commercialization of these tests is cheap and easy.

The critics have been heard and are finding resonance in the legislative, judicial, and executive branches. Legislation to limit the patentability of genetic inventions and the enforceability of genetic patents has been introduced in Congress, although not yet enacted. Omnibus patent reform legislation enacted in 2011 does contain a section requiring the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“PTO”) to conduct a study examining the “impact that current exclusive licensing and patents on genetic testing activity has on the practice of medicine, including but not limited to the interpretation of testing results and performance of testing procedures,” and to report back to Congress with recommendations as to how to deal with presumed problems with respect to the ability of health care providers “to provide the highest level of medical care to patients” and of innovators to improve upon existing tests. In the courts, the alleged impact of genetic diagnostic patents on genetic research and the availability of diagnostic testing played an important role in litigation brought by the ACLU against the genetic testing company Myriad Genetics, challenging the validity of Myriad’s so-called “gene patents.” The ACLU won before the Supreme Court. The Obama administration filed amicus briefs in the Myriad litigation arguing against patent eligibility for patent claims allegedly relating to genetic testing, and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director Francis Collins has been an outspoken critic of patents on genetic tests.

The plaintiff’s victory in Myriad has not lessened the call for more severe restrictions on the availability of effective patent protection for innovative molecular diagnostics. When the Supreme Court invalidated some of Myriad’s patent claims relating to the BRCA breast cancer genes, a number of Myriad’s competitors were emboldened to enter the BRCA testing market, and Myriad responded by filing lawsuits alleging infringement of some of its remaining patent claims (patent claims that were not at issue in the previous litigation). In response, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) sent a letter to Francis Collins asking NIH to “use its march-in rights under the Bayh-Dole Act to force Myriad Genetics Inc. to license its patents related to testing for genetic mutations associated with breast and ovarian cancer.”

This essay addresses some of the criticisms that have been leveled against genetic diagnostic testing patents. It identifies the critical role that patents play not only in the discovery and development of new molecular diagnostic tests, but also in making these tests more accessible to the patients who can benefit from them. When we move beyond the improperly restricted and crabbed view of patents as incentivizing only discovery of new medical drugs or tests, we recognize that patents also have a fundamental role in incentivizing companies like Myriad to create markets for these new discoveries by investing in educating patients and their doctors and in facilitating the reimbursement of patients for the cost of the test via their insurance plans.

Molecular Diagnostic Tests and Personalized Medicine

To understand the important role of patents in molecular diagnostic testing, it is important to have a basic understanding of what these tests are and where they come from. This is important if only because there is substantial misinformation in the public policy debates about these innovative medical discoveries. Thus, a brief primer on the topic is in order.

Molecular diagnostic tests involve the detection and/or analysis of a molecular biomarker in a patient in order to discern clinically relevant information about that patient. Molecular biomarkers come in many forms – prostate-specific antigen (PSA), for example, is a protein biomarker used to diagnose prostate cancer, while high levels of glucose in the blood can serve as a biomarker for diabetes. Today some of the most promising biomarkers are genetic variations, which are detected by analyzing an individual’s genomic DNA. Some genetic variations in the human breast cancer genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, for example, can be used to predict the likelihood that an individual harboring that variation will develop breast or ovarian cancer. Although significant progress already has been made, scientists are just beginning to scratch the surface of the potential of molecular diagnostic testing. Research continues in the quest to identify and validate new biomarkers correlated with a host of diseases and disease outcomes.

Testing for molecular biomarkers is not only useful in the diagnosis and prognosis of disease; it can also be used to guide doctors in the best course of treatment tailored to the needs of an individual patient. Personalized medicine, for example, encompasses the use of molecular diagnostic testing to identify the best course of drug therapy for an individual patient by (1) identifying the best drug for that individual, or (2) predicting the optimal drug dosage for that particular patient in terms of safety and efficacy. In a case involving determining personalized levels of drug dosage, Mayo v. Prometheus, the Supreme Court recently invalidated patent claims covering a non-genetic molecular diagnostic test that enables doctors treating patients for Crohn’s disease to prescribe a drug dosage at a level that maximizes efficacy while minimizing the horrible side effects too often endured by patients before the test became available. In doing so, the Court overturned a decision by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit which upheld the validity of the claims – the Federal Circuit’s decision explicitly acknowledged that the claims relate to methods of medical diagnosis and treatment which have until recently been assumed to constitute patentable subject matter.

The fundamental challenge in developing molecular diagnostic tests is identifying and validating clinically significant molecular biomarkers. The magnitude of this challenge is vastly underappreciated by those who argue against patent protection for these tests. It is true that some relatively rare genetic diseases such as sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis and Tay-Sachs are associated with specific genetic variations (sometimes referred to as mutations), and once those variations have been identified it is relatively straightforward for any competent clinical laboratory to test for the presence of a mutation that has been unambiguously associated with the disease. But these are the low hanging fruit. For the vast majority of human diseases which have a genetic component, the correlation between biomarker and clinically relevant information is much less straightforward, and substantial investment is necessary to support the lengthy and labor-intensive research efforts required to discern and validate the clinical significance of novel biomarkers.

With respect to any two individual humans there typically exists about 6 million genetic variations (referred to as polymorphisms) spread across the genome. Most comprise single nucleotide variations that occur on average about once in every 1000 nucleotides. Significantly, almost all of these polymorphisms are believed to be clinically irrelevant. Thus, the challenge is to identify that small cohort of human genetic variations that can function as useful biomarkers, and to assign and validate their clinical significance.

Compounding the difficulty is the fact that the clinical significance of most genetic variations is substantially affected by the influence of other genetic variations residing throughout the rest of the genome, oftentimes in a manner that is not additive, and by interactions with non-genetic environmental factors. For example, there is often an observed synergistic amplification of susceptibility to disease caused by the interaction of variations at multiple locations in the genome, or, conversely, a dampening of the effect of one variation caused by variations at other locations. It can be extremely difficult to identify and validate correlations for multifactorial genetic diseases of this type, which in large part explains the relatively modest progress that has been made in molecular diagnostic testing in the decade subsequent to the initial sequencing of the human genome.

For example, some genetic variations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast cancer genes have been shown to be associated with an extremely high likelihood of developing cancer, while others are associated with a likelihood of developing cancer only somewhat higher than the general population. Many of the observed variations in the BRCA genes are believed to be neutral, having no cancer-related implications. In fact, even after years of research and millions of dollars in investments, we are still finding patients with variations in the BRCA genes for which the significance is currently unknown. These “variations of uncertain significance,” or VUSs, constitute a major limitation on the clinical usefulness of molecular diagnostic tests. Patents provide the incentive for the substantial up-front investment in gathering and analyzing the clinical data necessary to assign a predictive value to a VUS.

Shrinking Patent Protection for Molecular Diagnostics and Personalized Medicine

For years, innovative scientists and physicians working in diagnostics and personalized medicine have sought and obtained patent protection for diagnostic tests that are based on the detection and/or analysis of molecular biomarkers. While patent claims covering isolated and synthetic DNA molecules can play some role in this regard, the most direct and effective means of patenting a diagnostic test is by claiming the method itself. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court’s recent decisions in Mayo and Myriad have substantially impaired the ability of innovators to obtain effective patent protection for DNA molecules used in diagnostic testing and for diagnostic testing methods per se. Although Myriad has garnered more public attention, Mayo is likely a much more significant decision with respect to the patentability of diagnostic tests, since it most directly implicates the method claims which are so important for effective patent protection in this area of technology.

Three aspects of Mayo could prove extremely problematic for future patenting of molecular diagnostics in general. First, the Court adopted a very broad definition of the term “natural phenomena” as it is applied in the context of patent eligibility for discoveries in medical treatments. The Mayo Court’s definition of this term, which refers to facts of nature that are unpatentable, appears to encompass the discovery of clinically significant biomarkers that is the essence of innovation in diagnostics and personalized medicine. Second, the Court held that in order to be patent eligible, a method claim must include some “inventive concept” above and beyond the discovery of a natural phenomenon. And third, the Court declared that a method claim is patent ineligible if it “preempts” all practical applications of a natural phenomenon.

A recent district court decision, Ariosa Diagnostics v. Sequenom, illustrates the profoundly troubling implications of Mayo for patents on molecular diagnostic methods. On a motion for summary judgment, the judge invalidated all of the genetic diagnostic testing method claims at issue in the case for failure to satisfy the requirements of patent eligibility as set forth in Mayo. In particular, the judge held that the claims failed the “inventive concept” test because they encompassed conventional methods of DNA analysis, and failed the “preemption” test based on a determination that the claims would cover all “commercially viable” methods of performing the test as of the filing date of the patent.

If this is indeed the standard by which the validity of molecular diagnostic claims will be assessed, the prospect for effective patent protection appears bleak. Innovation in molecular diagnostics resides primarily in the identification and characterization of biomarkers of clinical significance, e.g., genetic variations useful in the diagnosis and prognosis of disease. Once the biomarker and its clinically significant correlation has been identified, conventional forms of DNA analysis involving techniques such as PCR amplification and/or labeled hybridization probes are employed for diagnostic testing. A patent eligibility test that bars the inventor from claiming the use of conventional DNA analysis techniques will render the patent ineffective in blocking competitors from entering the market and thereby free-riding on the initial inventor’s substantial investments in the discovery of this molecular biomarker.

This troubling concern is not mere prophecy. In Ariosa Diagnostics,the judge held that Mayo prohibits any patent claim that encompasses all “commercially viable” means of testing for a biomarker. This decision renders any protection afforded by a valid diagnostic patent illusory. After all, how many venture capitalists are interested in investing hundreds of millions of dollars in a start-up diagnostic company whose patents are unable to preclude competition by free-riders using alternate, unpatented (but still commercially viable) methods for detecting the same biomarkers that the start-up invested in identifying?

Furthermore, in Myriad, the Supreme Court held that isolated DNA molecules corresponding to naturally occurring DNA are patent ineligible, absent some significant structural difference compared to the naturally occurring molecule. This holding is problematic for innovators in genetic testing because the DNA molecules used in the course of genetic diagnostic testing, such as DNA primers for PCR and hybridization probes, are inherently highly similar in chemical structure to naturally occurring DNA molecules, and thus apparently patent ineligible under Myriad. A district court recently adopted this view in a decision denying the patentee’s motion for preliminary injunction against an alleged infringer in a lawsuit commenced post-Myriad, finding that product claims directed towards DNA primers useful in BRCA genetic testing are likely invalid under Myriad. The PTO recently issued guidance adopting the same restrictive interpretation of Myriad with respect to DNA primer claims.

The Role of Patents in Molecular Diagnostic R&D

The Unfounded Assumption that Patents Inhibit Research

The plaintiffs in Myriad argued that Myriad’s patents inhibit research that might otherwise lead to improvements in BRCA testing. Unfortunately, many share this pessimistic view of the role of patents in the research and development of molecular diagnostic tests, and this deeply mistaken notion found support in a number of amicus briefs filed with the Supreme Court in support of the Myriad plaintiffs. A typical example was an amicus brief filed by the American Medical Association, which argued that patents are not only unnecessary to incentivize the optimal level of innovation in genetic diagnostic tests, but that genetic diagnostic patents allegedly inhibit research that could develop improved tests.

The argument that patents inhibit research in genetic diagnostics is based largely on an unfounded assumption that the existence of a patent necessarily precludes research on the patented subject matter. In fact, empirical studies have shown that basic researchers follow a norm of ignoring patent infringement, and that patent owners do not enforce their patents against basic researchers, resulting in a de facto research exemption from liability. Patent owners have little if any incentive to enforce patents against basic researchers – to the contrary, patent owners often welcome third-party basic research on patented subject matter, since it tends to promote and enhance the value of the patented subject matter.

Myriad’s policy toward basic research on the BRCA genes is a good case in point. During the time in which Myriad’s BRCA patents have been in force, basic research on the BRCA genes has flourished in both the US and abroad. While patent-skeptics assume that Myriad’s patents preclude research on the genes, in fact thousands of research articles relating to the genes have been published, many by researchers at leading US academic institutions such as the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Chicago, Emory University, and the University of Rochester. While it has been widely publicized that Myriad has on occasion threatened lawsuits against academic institutions that engaged in genetic diagnostic testing, it is important to bear in mind that these academic institutions were invariably engaged in commercial genetic testing, not basic research – i.e., they were charging patients for the testing services and thus competed with Myriad.

In attempting to support their assertion that patents harm research and development of diagnostic tests, patent-skeptics often point to the “SACGHS Report,” a 2010 report on the impact of patents on patient access to genetic tests that was prepared by the Secretary of Health and Human Services’ Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health, and Society. Despite these citations to the SACGHS Report, the case studies presented in the SACGHS Report for the most part show exactly the opposite. For example, the Report’s case study on the impact of patents and patent licensing practices on access to genetic testing for hereditary hemochromatosis concluded not only that “concerns regarding inhibition of research due to the HFE gene patents do not seem to be supported,” but that substantial basic research aimed at identifying new genes and genetic variations associated with hemochromatosis, along with new methods of testing for these biomarkers, were proceeding in spite of third-party patents. Similar findings were reported with respect to genetic tests investigated in other case studies, including the tests for cystic fibrosis, hearing loss, and Alzheimer’s disease.

The Important Role of Patents in the Development and Commercialization of Diagnostic Tests

While patents do not inhibit basic research, they do play a critical role in incentivizing the substantial investment required to translate the results of basic research into high-quality, commercially available diagnostic tests that meaningfully impact people’s lives. In a recent report, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology found that the “ability to obtain strong intellectual property protection through patents has been, and will continue to be, essential for pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies to make the large, high-risk R&D investments required to develop novel medical products, including genomics-based molecular diagnostics.” Similarly, commentators familiar with the challenges associated with the development and commercialization of diagnostics have concluded that patents are vital “to incentivize the significant investment required” for clinical research in personalized medicine. And while the AMA came out against genetic diagnostic testing patents in Myriad, the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons (“AAPS,” a national nonprofit association representing thousands of physicians) filed an amicus brief in support of Myriad’s patents, explaining that “advancing patients interests means supporting and defending incentives for medical innovations.”

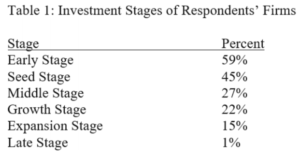

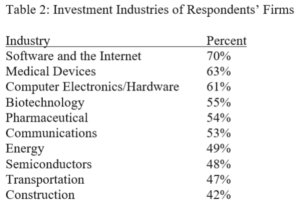

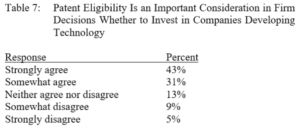

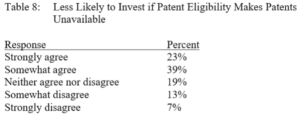

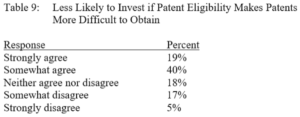

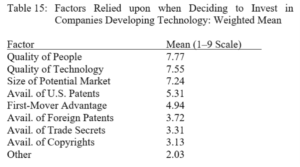

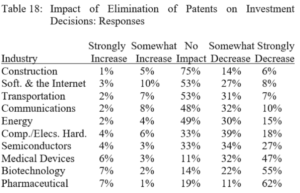

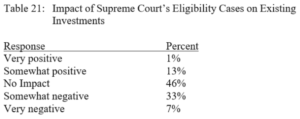

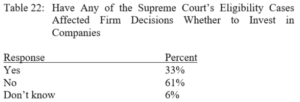

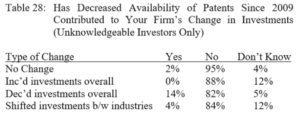

Innovators in molecular diagnostics rely heavily on venture capital to fund the years of research, development, and validation necessary to bring a novel diagnostic product to market, and the decision of whether to invest is heavily dependent upon the availability of effective patent protection. Weakening of patent protection for molecular diagnostics will inevitably cause venture capitalists to shift their investments to other sectors of the economy. Not surprisingly, the National Venture Capital Association filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court in support of Myriad.

One of the most compelling amicus briefs submitted to the Supreme Court insupport of Myriad was filed by Lynch Syndrome International (“LSI”), an all-volunteer organization founded and governed by Lynch syndrome survivors, their families, and health care professionals who treat Lynch syndrome. Lynch syndrome is a genetic condition caused by genetic variations in certain genes that result in a greatly increased risk of developing colon cancer. Lynch syndrome and BRCA mutations are highly analogous, with one important difference – patents in the area of Lynch syndrome have been nonexclusively licensed, so there has been no single provider to invest in developing and improving genetic tests for Lynch syndrome, nor in making the test widely available to the patients who could benefit from it. In its brief, LSI argues passionately for greater patent protection in the area of genetic diagnostic testing, in the hope that patent exclusivity might incentivize a patent owner to invest in Lynch syndrome in a manner comparable to Myriad’s investment in BRCA testing.

LSI explains that:

The development and commercialization of genetic tests require significant amounts of capital, but capital sources will not provide the necessary funding unless the newly developed tests will have patent protection. Only patent protection will assure the capital sources of sufficient investment return to make the provision of funding worthwhile.

LSI’s brief goes on to urge the Supreme Court to maintain patent eligibility for genetic tests in the hope that patents might provide incentives for the development of high-quality tests comparable to those available for BRCA thanks to the investments made by Myriad. LSI points to the long odds against success facing start-up companies like Myriad, noting that most start-up companies fail, particularly in the area of diagnostics. In the words of LSI:

Myriad’s survival, due largely to patent eligibility for genetic tests, has been a miracle for BRCA1 and BRCA2 patients: without Myriad, it is possible that only fragmented and potentially unregulated testing would be available. Lynch syndrome patients desperately need access to the quality testing that Myriad has been able to provide to BRCA1 and BRCA2 patients.

While the SACGHS Report found little evidence that patents impede basic research, it also found (incorrectly) that patents are largely unnecessary for genetic research, based largely on an assumption that genetic research is primarily conducted by academics who are not particularly interested in obtaining patents. The Report opines that while patents incentivize some private investment in genetic research, this private funding is “supplemental to the significant federal government funding in this area.” In conclusion, the Report states that “patent-derived exclusive rights are neither necessary nor sufficient conditions for the development of genetic test kits and laboratory-develop tests.” But these conclusions are seriously flawed, as explained below.

When the Report assumes that most genetic research is conducted by academic researchers, it is specifically referring to the identification of genes associated with genetic disease. While finding a gene associated with genetic disease is an important first step, the Report fails to take into account the much more difficult and costly research required to discern and validate the clinical significance of genetic variations. The Report’s conclusions, based on an analysis of the relatively straightforward genetic diseases that have been the basis for the first round of genetic diagnostic tests, are largely inapplicable to the next generation of diagnostic tests, where the correlation between genetic variation and clinical significance will be much more attenuated and difficult to establish.

The BRCA genes provide a good example of this. While the discovery of the genes in the 1990s was an important first step, the real work began after the genes were identified, as Myriad and others sought to distinguish the clinically significant variations in the BRCA genes from the clinically insignificant, and to quantify and validate the likelihood of cancer for patients having clinically significant variations. Some variations have been shown to correspond with only a marginal likelihood of cancer, others with a very high likelihood. Myriad reports that even today 3% of the variations it finds when it tests patients are still of unknown significance, and this is after performing thousands of tests and compiling enormous amounts of data. In Europe, where for years Myriad has as a practical matter not enforced its patents, many independent laboratories perform BRCA tests. The number of variations of uncertain significance in Europe is much higher than in the US, not surprising since without an exclusive provider there is less incentive and ability to gather and analyze the data necessary to assign significance to ambiguous variations.

Celera Diagnostics, a private-sector developer of advanced diagnostic tests, made this point in a comment submitted in connection with the SACGHS Report:

Even though the Draft Report suggests that scientists who search for gene-disease associations may not be motivated by the prospect of receiving a patent, they cannot conduct this type of research without considerable capital and resources. In our experience, meaningful gene-disease associations are confirmed only if the initial discoveries are followed by large scale replication and validation studies using multiple sample sets, the costs of which are prohibitive for many research groups. Private investors who provide funding for such research invariably look to patents that result from such work as a way of protecting their investment.

The SACGHS Report concluded that patents are unnecessary for the development and commercialization of diagnostic test, but that conclusion was based on an unrealistic assumption that the cost of developing a sequencing-based diagnostic test is in the range of $8,000-$10,000. While this paltry sum might have been sufficient for the development and commercialization of the simple diagnostic tests considered by SACGHS in preparing its Report, it is orders of magnitude short of the investment required for the critical next generation of diagnostic tests being developed by companies such as Myriad, Celera, and Genomic Health.

Furthermore, patents also promote innovation by facilitating collaboration and coordination between firms, which will be particularly important in the development of personalized medicine. For example, the pairing of the cancer drug Herceptin with a companion genetic diagnostic test that identifies patients likely to benefit from treatment with Herceptin represents one of the first successful implementations of personalized medicine. Herceptin, a biotechnology drug developed by Genentech, is only effective for a subpopulation representing about 30% of breast cancer patients, but for those for which it is effective it can reduce the recurrence of a tumor by 52%. Another pharmaceutical company, Abbott, developed the companion genetic diagnostic test used to distinguish between patients who will benefit from Herceptin and those who will not. The distinction is important because it allows doctors to rapidly begin Herceptin treatment for patients who will benefit from it, while avoiding the high cost and delay that result from trying Herceptin on a patient that, for genetic reasons, will not respond to the treatment. Patents play an important role in incentivizing companies like Abbott to develop a companion diagnostic, as well as facilitating the collaboration necessary to effectively pair one company’s diagnostic with another company’s drug.

Now that Myriad’s patent protection has been weakened, some argue that the company should make its proprietary data freely available in order to allow competitors to improve their tests. At one time Myriad did share this data, but in recent years it has adopted a policy of maintaining much of it as a trade secret. Of course, this is exactly the response one would predict in the face of weakened patent protection. No company is likely to invest in the creation of a valuable database if competitors are free to appropriate the value of the data. An important attribute of patents is that they encourage the disclosure of information that in the absence of the patent would likely be kept as a trade secret. Indeed, the SACGHS Report explicitly recognized that an absence of patent protection promotes secrecy, and that such “secrecy is undesirable because the public is denied new knowledge.”

The Important Role of Patents in Promoting Access

One of the main complaints leveled against patents on genetic diagnostic tests is that a patent owner like Myriad is able to charge a higher price as the exclusive test provider, which limits access for patients who cannot afford the test. A study included in the SACGHS Report attempted to assess this allegation by comparing the cost for Myriad’s BRCA test with the genetic test for Lynch syndrome. When normalized for the relative sizes of the genes, the Report found that Myriad charges “little if any price premium” for its exclusively controlled BRCA testing relative to the price charged for nonexclusively licensed testing of the Lynch genes. The Report concluded that this “surprising” finding “suggests that the main market impact of the BRCA patents is not on price but rather on volume, by directing BRCA full-sequence testing in the United States to Myriad, the sole provider.”

While the prices of BRCA and Lynch syndrome testing are comparable, many more BRCA tests are performed in the US compared to Lynch syndrome testing, suggesting that, at least with respect to these two tests, patent exclusivity actually serves to enhance patient access. Epidemiologically the two syndromes are quite similar – both have a similar prevalence in the overall population and in cancer populations, both can result in drastic increases in the risk of developing cancer, and breast and colon cancer are two of the leading causes of cancer death in the country. Prior to the Myriad decision there were 15 providers of full sequence Lynch syndrome testing in the US, and only one authorized provider of full sequence BRCA testing (Myriad). However, in the period from June 2010 through March 2013 nearly 5 times as many patients in the US received BRCA testing than testing for Lynch syndrome (339,294 vs. 70,294).

One explanation for the discrepancy could lie in the relative quality of the tests. The turnaround time for Lynch syndrome testing results is reportedly longer than that of Myriad’s BRCA tests, and the VUS rate is much higher for Lynch syndrome (15-30% for non-Myriad Lynch testing vs. 3% for Myriad BRCA testing). The amicus brief filed by LSI specifically noted the superiority of Myriad’s BRCA test, which LSI attributed to the patent exclusivity enjoyed by Myriad with respect to the BRCA genes.

Increased public awareness of BRCA testing relative to Lynch syndrome testing is likely to account for much of the discrepancy in usage of the tests. The SACGHS Report specifically found that the “incentive to advertise the service and broaden the market is stronger for a monopoly provider than in a shared market because a monopolist will gain the full benefit of market expansion.” According to the Report, one of the social benefits of patents is that they incentivize an exclusive test provider like Myriad to invest in creating more public knowledge of the availability of genetic tests. The Report acknowledges a clear “link between [Myriad’s] status as a single provider and incentives for direct-to-consumer advertising, with single provider status in this case associated with exclusive patent rights for BRCA testing.”

A Center for Disease Control (CDC) survey found an increase in BRCA test requests and questions about testing among women, and an increase in test-ordering among physicians and providers, in cities where Myriad invested in direct-to-consumer “public awareness campaigns.” The SACGHS Report noted that “[t]he overall impact of a DTC advertising campaign on the Kaiser Permanente health system in Denver was a more than two-fold increase in number of women in the high risk category getting tested, a more than three-fold surge in contacts about testing.” Another study showed that high-risk women—those eligible for BRCA testing based on family history—were three times as likely to get tested following a physician recommendation as those who did not get such a recommendation.

Ironically, while Myriad fought to inform patients and healthcare providers about the availability of BRCA testing, many policymakers argued in favor of restricting patient access to the results of these tests. For example, the Working Group of Stanford’s Program in Genomics, Ethics and Society recommended that ‘for most people, testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations is not appropriate.’ Similarly, NIH director Francis Collins testified before Congress that the results of genetic testing for BRCA mutations should generally not be made available to patients. With respect to BRCA testing, patents have played an important role in empowering patients to take control of their own their own genetic information, in the face of a medical establishment that sought to limit patient access to this information.

One of the most formidable obstacles facing patients in need of genetic diagnostic testing services is insurance reimbursement. Patents play an important role in overcoming this obstacle, by providing an incentive for patent owners to work with insurance companies to ensure that a maximum number of patients will be able to get insurance reimbursement for testing. For example, in 1995 only 4% of insurance providers allowed reimbursement for BRCA genetic testing. By 2008 Myriad was able to report that it had established contracts or payment agreements with over 300 carriers and has received reimbursement from over 2500 health plans, reducing the number of self-pay patients to single-digit percentages of its clientele. By 2010 BRCA genetic testing in the U.S. was covered for roughly 95% of those requesting tests, and reimbursed to cover 90% of their charges. In contrast, non-profit diagnostic testing services in many cases charge patients upfront for genetic testing, and require patients to seek their own reimbursement from their insurance company, which can be slow in coming, assuming it comes at all.

Conclusion

Arguments in favor of reining in the availability of effective patent protection in the area of genetic diagnostic testing are based largely on two fundamental misconceptions regarding the role of patents in this important area of technological innovation. The first is the mistaken assumption that patents negatively impact patient access to genetic diagnostic testing by preventing research that might lead to new or improved versions of a genetic test and by increasing the cost of testing services. The second is the failure to appreciate the substantial positive role patents play in in the development and utilization of genetic diagnostic tests. In fact, patents have little if any negative impact on basic research, and have been proven to significantly improve patient access to advanced diagnostic testing services by incentivizing the substantial investment that is necessary not only to bring these tests to market, but also to educate patients and their doctors with respect to the availability of the tests, and to work with third-party payers to expand patients’ eligibly for reimbursement. Next-generation technologies are poised to dramatically improve healthcare and patient outcomes, but this will only occur if effective and enforceable patent protection is available as the necessary spur for innovation and commercialization.

In Tuesday’s

In Tuesday’s  Following the Supreme Court’s four decisions on patent eligibility for inventions under

Following the Supreme Court’s four decisions on patent eligibility for inventions under