The following guest post from Robert R. Sachs, Partner at Fenwick & West LLP, first appeared on the Bilski Blog, and it is reposted here with permission.

By Robert R. Sachs

The most important thing that happened in June was not the invalidation of yet another pile of patents, but the rather more consequential decision of the Supreme Court to recognize the right of same-sex couples to marry. Unlike patent law issues, when it comes to constitutional law, the Court can recognize the complexity and depth of the issue and, not surprisingly, the Court is deeply divided. That the Court is unanimous on equally complex and divisive issues in patent law—such as eligibility—speaks to me that they do not have the same deep understanding of the domain.

The most important thing that happened in June was not the invalidation of yet another pile of patents, but the rather more consequential decision of the Supreme Court to recognize the right of same-sex couples to marry. Unlike patent law issues, when it comes to constitutional law, the Court can recognize the complexity and depth of the issue and, not surprisingly, the Court is deeply divided. That the Court is unanimous on equally complex and divisive issues in patent law—such as eligibility—speaks to me that they do not have the same deep understanding of the domain.

Now, let’s do the #AliceStorm numbers. First, the federal courts:

Since my May 28 update, there have been 19 § 101 decisions including two Federal Circuit decisions, Internet Patents Corp. v. Active Network, Inc. and Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Sequenom, Inc., both holding the challenged patents ineligible. Overall, the Federal Court index is up 3.1% in decisions and an (un?)healthy 6.2% in patents. The Motions on Pleading index is holding steady; the last five decisions on § 101 motions to dismiss have found the patents in suit invalid.

We can look more specifically at the invalidity rate by type of motion and tribunal:

For example, the 73.1% invalidity rate in the federal courts breaks down into 70.2% (66 of 96) in the district courts and a stunning 92.9% in the Federal Circuit (13 for 14). Motions on the pleadings and motions to dismiss are running equally, at a 69% defense win rate.

The 73.7% summary judgment success rate is consistent with the high rate on motions to dismiss. Since the courts have taken the position that there are no relevant facts to patent eligibility and there is no actual presumption of validity in practice, there is now little difference between the underlying showings required for the two types of motions. That’s odd since on the motions to dismiss the court is to look only at the pleadings, while on summary judgment they have the full file history, expert testimony, the inventor’s testimony and other evidence before them. Why such evidence is not helping—and indeed appears to be hurting—patentees is because the court is evaluating it from their lay perspective. In my opinion, the correct perspective is that of a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSITA). What a court may consider merely abstract may be easily recognized as a real-world technology by an engineer; a claim term that appears trivial to a court (“lookup table”, “isolated”) or may be significant to the expert.

We can also evaluate how individual the various district courts are doing.

(The (-1) values in the bottom five rows indicate that the court held that patent was not invalid).

Of the 66 district court decisions since Alice that have invalidated patents on § 101, Delaware, the Central and Northern Districts of California account for 58% of the decisions. The most prolific judges are shown here:

Yet, when it comes to finding abstract ideas, the USPTO remains the champ. The best avenue to attack a patent under § 101 is through the Covered Business Method (CBM) review program. A challenger files an institution petition before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) arguing that the challenged patent is directed to a financial product or service, and setting forth their ineligibility arguments. PTAB then issues an institution decision as to whether to grant the petition or not. The standard at this stage is whether it is more likely than not that the claims are ineligible. Once instituted, there is a full proceeding leading up to a final decision as to whether or not the patent is invalid.

At PTAB, CBM institution decisions are up (19 since May 28), and PTAB leads the race with the courts with an 88.6% invalidity rate on CBM institutions, and an unbeatable 100% rate (unchanged) on CBM final decisions.

If only the SF Giants could play their game this well.

Alice and the Patent Prosecutor

In my previous post, I drilled down in the impact of Alice on prosecution in terms of office action rejections and abandonments. My dataset was some 300,000 applications for the pre- and post-Alice period prepared for me by the team at Patent Advisor. Since then, I’ve received an additional 190,000 samples, comprising all office actions issued by the USPTO in September and October 2014. Together, the data set has over 490,000 office actions and notices of allowances:

The additional data from September and October fill in the trends in § 101 rejections that I showed before. As I explained, Tech Center 3600 includes more than just business methods, including literally down-to-earth technologies like earth moving and well boring. The § 101 rejections are concentrated in three E-commerce work groups:

There is some good news for software. The computer-related art units, TC 2100 and TC 2400, show considerably lower and steady § 101 rejection rates pre- and post-Alice.

After Alice, I think most software prosecutors expected to get non-final § 101 rejections, and consistent with past practice, expected to overcome them by amendment and argument. That would lead to final rejection based on prior art or an allowance. And that’s generally been true—except in a number of areas. In this following table, I compare the percentage of final office actions with § 101 rejections before and after Alice, in various Tech Centers and within TC 3600.

It’s important to remember the obvious: that you don’t get to a final rejection on § 101 without a first having a non-final rejection. Thus, this comparison shows how successful prosecutors were in overcoming non-final § 101 rejections before and after Alice—or equally how aggressive examiners were in maintaining these rejections. For example, before Alice 8.1% of final rejections in TC 1600 included a § 101 rejection, doubling to 16.7% after Alice—thus indicating that examiners were much more likely to maintain the rejection after Alice, but still a relatively low rate overall. By comparison in TC 2600, the rate of final rejections on § 101 declined after Alice, from 10% to 7.7%. This could be because it’s easier to explain why an invention in more traditional fields is an improvement in technology, one of the Alice safe harbors.

But when it comes to business methods, we see the killer statistics: prior to Alice, prosecutors overcame the non-final § 101 rejections generally about 62% of the time, leading to final rejection rates in the 23-46% range; thus prosecutors had more or less even odds of getting over the rejection. What is shocking is that after Alice, the final rejection rate soared into the 90% range. If you felt frustrated that your crafted (or crafty) arguments failed to impress the Examiner, get in line.

Now I’ve reviewed several hundred post-Alice rejections, and I’ve talked to a large number of prosecutors. What I’ve found is that majority of the non-final § 101 rejections were relatively formalistic, with little actual substantive analysis. Likewise, in a review of 87 office actions issued in November 2014 with § 101 rejections, Scott Alter and Richard Marsh found that 63 percent of those actions were “boilerplate” rejections. In my view, most prosecutors put forward at least a decent argument to show that the claims are not abstract, have at least one significant limitation, and do not preempt the abstract idea. Response arguments to § 101 rejections tend to run longer than response to prior art rejections, and I’ve seen many that resemble appeal briefs if not legal treatises, all to overcome a one paragraph rejection. They all presented at least enough of an argument to overcome the prima facie case for the rejection. And yet the final rejections keep coming—and often with little or no substantive rebuttal of the prosecutor’s arguments.

Outside of business methods, I found only two technology areas that had post-Alice rejection rates in excess of 30%: Amusement and Education devices in Tech Center 3700 (bottom row above) and molecular biology/bioinformatics/genetics in TC 1600 (not shown). This is a peculiar side effect of Alice. Historically, games and educational devices are classic fields of invention. There are thousands of patents on games, such as card games, board games, physical games, and the like. What is now hurting these applications are two aberrations in the law of patent eligibility: mental steps and methods of organizing human activity. The majority of § 101 rejections for games argue that the rules that define a game are simply ways of organizing human activity and can be performed by mental steps. Examiners typically cite the Federal Circuit’s Planet Bingo v. VKGS decision for the proposition that a game is an abstract idea and can be performed mentally. Only a small problem here: Planet Bingo is non-precedential and thus limited to its facts. In particular, the court did not hold that the game of bingo was an abstract idea. Instead, the alleged abstract idea was of “solving a tampering problem and also minimizing other security risks during bingo ticket purchases.” Thus, the case cannot be extended by examiners to argue that all games are abstract ideas.

As to methods of organizing human activity, it cannot be the case that all such methods are ineligible, since a vast array of such methods are in fact patented in fields such as farming, metalworking, sewing, manufacturing, tooling, conveying, and the like. This is just another example how simplistic rules of patent eligibility, taken out of context from one court opinion and repurposed generally, are at complete odds with the reality of invention.

Here is another view of the final rejection data on § 101, this time organized by the technology groups most negatively impacted by Alice (left side) and most positively impacted (right side).

The data here is organized by the percentage change in § 101 final rejection rates post-Alice. The group on the left is all of the technology areas that have had more than a 10% increase in final § 101 since Alice. Every other technology work group in the USPTO had less than 10% change in final rejection rates. On the right, we find the groups that seemed to benefit from Alice, in that the final rejection rates on § 101 declined. Most of these groups are in the computer area—and I’m sure that many of their applications have claims for purely software operations that could just as easily be argued to be mere data gathering, mental steps, or fundamental practices. And yet the examiners in these groups do not on average impose such blanket formulations on the claims, but appear overall to treat these inventions for what they are: real technology solving real world problems with real commercial applications.

To me, the data points to a clear conclusion. Contrary to what the USPTO’s Interim Guidance states as policy–that there is no per se exception for business methods–the behavior of examiners suggests that precisely such an exception is being applied in fact.

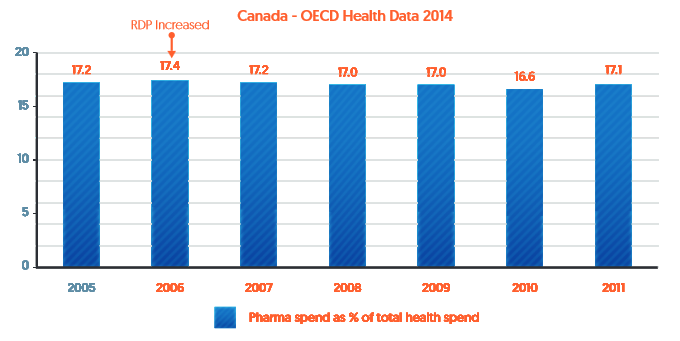

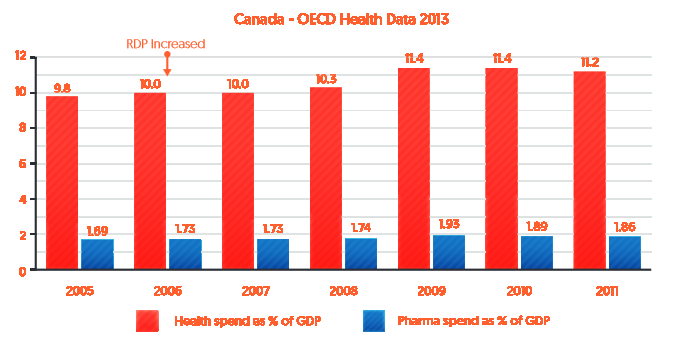

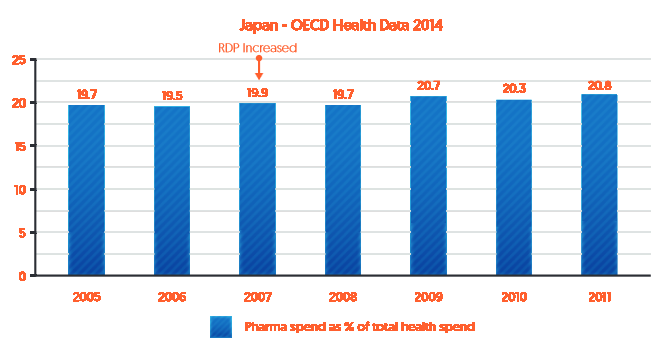

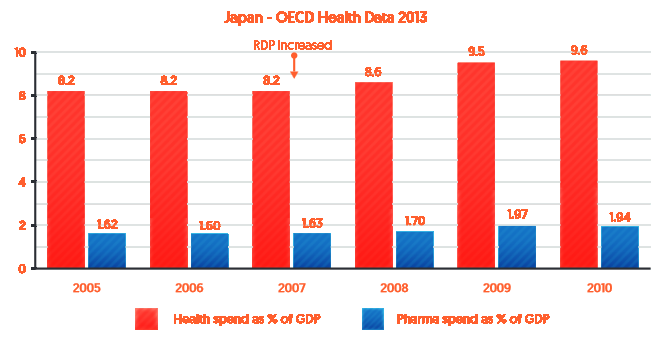

In the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations, the U.S. and Japan have proposed that TPP partners increase their period of regulatory data protection (RDP) for biologic medicines to align with practice in other countries. These proposals have been strongly opposed by a number of academics, who claim that such a move would significantly increase public spending on medicines, thereby potentially limiting access.

In the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations, the U.S. and Japan have proposed that TPP partners increase their period of regulatory data protection (RDP) for biologic medicines to align with practice in other countries. These proposals have been strongly opposed by a number of academics, who claim that such a move would significantly increase public spending on medicines, thereby potentially limiting access.

In

In  By

By  In the last two weeks, the House and Senate Judiciary Committees marked up wide-ranging patent legislation ostensibly aimed at combating frivolous litigation by so-called “patent trolls.” But while the stated purpose of the House and Senate bills—H.R. 9 (the “

In the last two weeks, the House and Senate Judiciary Committees marked up wide-ranging patent legislation ostensibly aimed at combating frivolous litigation by so-called “patent trolls.” But while the stated purpose of the House and Senate bills—H.R. 9 (the “