By Matthew Barblan & Kevin Madigan

One of the oddities of US copyright law is that sound recordings—the way that our favorite songs are captured on media so that we can listen to them over and over again—were not protected under federal law until the early 1970s. Unfortunately, when the federal Copyright Act was finally amended in 1971 to incorporate sound recordings, copyright protection for sound recordings was not applied retroactively. As a result, artists who recorded music before February 15, 1972 (the effective date of the 1971 Sound Recording Amendment) have been unable to use federal copyright law to safeguard their valuable creative contributions to American music.

One of the oddities of US copyright law is that sound recordings—the way that our favorite songs are captured on media so that we can listen to them over and over again—were not protected under federal law until the early 1970s. Unfortunately, when the federal Copyright Act was finally amended in 1971 to incorporate sound recordings, copyright protection for sound recordings was not applied retroactively. As a result, artists who recorded music before February 15, 1972 (the effective date of the 1971 Sound Recording Amendment) have been unable to use federal copyright law to safeguard their valuable creative contributions to American music.

Next week, the House Judiciary Committee will mark up a legislative package that includes the CLASSICS Act (“CLASSICS” stands for Compensating Legacy Artists for their Songs, Service, & Important Contributions to Society). The CLASSICS Act creates a digital public performance right for pre-1972 sound recordings, and in doing so addresses an inequity that has persisted for decades. By giving legacy artists the ability to protect and license the use of their sound recordings in modern distribution platforms, the CLASSICS Act represents an important first step in recognizing the hard-earned property rights of countless American artists who recorded their music before 1972.

With the markup of the CLASSICS Act fast approaching, it’s fitting to look back on the peculiar history of US copyright in sound recordings and trace the events that lead to the current inequitable state of affairs. This essay first examines how sound recordings have been treated by US copyright law over time, discussing the erstwhile promise and eventual shortcomings of enforcing digital public performance rights at the state level. The article then analyzes the CLASSICS Act and discusses how the bill represents important progress in fairly compensating and securing property rights to the myriad legacy artists whose recorded music continues to influence and inspire us in the twenty-first century.

A Longstanding Struggle for Recording Artists

Sound recordings have played a vital role in the development of American art since the late 19th century when luminaries such as Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison revolutionized the fixation of sound. In addition to chronicling the rich evolution of musical genres from jazz to rock ‘n’ roll, sound recordings of folklore, radio broadcasts, speeches, and other spoken words make up an invaluable account of the American experience. But despite attempts by some of the first record companies in the early twentieth-century to secure federal copyright protection for sound recordings, the Copyright Act of 1909 only secured copyright protection to owners of the musical compositions that are the subjects of sound recordings, but not to sound recordings themselves.

The US Copyright Office’s 2011 report on pre-1972 sound recordings explains that, without federal copyright protection, administration of the infringement of sound recordings was left to the states through a patchwork of unfair competition laws and common law copyright. In the 25 years between 1925 and 1951, over 30 bills were introduced in Congress that would have extended some form of federal copyright protection to sound recordings, but as the Copyright Office report notes, none passed due to opposition “based on technical deficiencies and concerns about their constitutionality (both as to whether sound recordings were creative, and whether they were writings).”

It wasn’t until 1971—after years of review and an important study on sound recordings by former Register of Copyrights Barbara Ringer—that Congress passed the Sound Recording Amendment, which finally secured federal copyright protection for sound recordings. A key reason Congress acted in 1971 was the failure of state statutes and common law to adequately protect sound recordings in the face of an alarming rise in audio tape piracy. Copyright owners had become increasingly frustrated with having to rely on a hodgepodge of state unfair competition laws to protect their property rights against infringers, finding that even if they were successful, remedies were often limited. Additionally, the very validity of state law protection of sound recordings had been challenged in high profile cases by defendants who argued that any state law provision was preempted by federal law, despite the fact that no federal law existed to protect copyright in sound recordings.

The Sound Recording Amendment to the Copyright Act took effect on February 15, 1972, but it only secured copyright protection for sound recordings fixed on or after that date, and it omitted certain rights guaranteed to other works of authorship. The 1976 Copyright Act ultimately included sound recordings as protectable subject matter, but it too failed to secure copyright protection in pre-1972 sound recordings, and it also failed to provide sound recordings with the full scope of exclusive rights secured to other types of creative works. According to the Copyright Office’s 2011 report, it’s unclear why Congress didn’t address the issue of pre-1972 sound recordings a long time ago, but the report suggests that it was a mistake of not fully understanding the consequences of leaving these works (and artists) behind. Whatever the reason, for over 45 years since passing the 1971 Sound Recording Amendment, Congress has left pre-1972 sound recordings under the aegis of state law.

A Failure at the State Level

Left behind by the federal copyright revisions, pre-1972 sound recording owners and recording artists have long faced a web of inconsistent state criminal and civil laws. Making matters worse, many states simply do not have adequate statutes or common law causes of action to address the growing varieties of infringement that we see today, and it is often impossible to predict how courts will apply broad common law principles or unfair competition statutes to infringement claims.

The vague and varying nature of states’ protection of pre-1972 sound recordings has frustrated recording artists and copyright owners for many years, but the most vexing issue today involves digital public performances of these works. The Copyright Act was amended in 1995 to provide copyright protection for the public performance of sound recordings “by means of a digital audio transmission,” but like other federal copyright protections for sound recordings, pre-1972 sound recordings were not included. The struggles of the 1960’s-era rock band The Turtles in their high profile attempts to use state law to protect their sound recordings against digital public performance infringement provide an emblematic example of why state law is largely inadequate to protect the creative contributions of pre-1972 recording artists.

In 2013, Turtles members Flo & Eddie filed a class action suit against Sirius XM in California for infringement of millions of pre-1972 sound recordings, arguing the satellite broadcaster played the songs without permission and without paying royalties to the artists. After bringing suit in California, Flo & Eddie filed similar class action claims against satellite radio services in New York and Florida, setting up a showdown that would—for better or worse—bring additional clarity to the landscape of state law protection of sound recordings in the digital streaming age.

Despite early optimism and a conditional settlement agreement with Sirius, in 2016, the New York Court of Appeals (the highest court in the state) dealt a blow to Flo & Eddie when it ruled that New York state law did not protect public performances of pre-1972 sound recordings. Critics of the ruling pointed out that the opinion contains many logical flaws and that the court ruled in favor of Sirius mainly because of concerns over the potential disruption that a ruling in favor of Flo & Eddie would cause. In 2017, the Florida Supreme Court echoed the New York opinion, holding that Florida law doesn’t recognize public performance rights for recordings made before 1972. The Florida Supreme Court made no mystery of a chief reason for their finding, admitting that to find otherwise “would have an immediate impact on consumers beyond Florida’s borders and would affect numerous stakeholders who are not parties to this suit.”

The main remaining battleground for Flo & Eddie is the California Supreme Court, which has yet to rule on the issue, but regardless of the California outcome for Flo & Eddie, the New York and Florida cases have exposed the failure of state law to protect the creative property of legacy recording artists.

The CLASSICS Act

On July 19, 2017, Representatives Jerry Nadler (D-NY) and Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) introduced the Compensating Legacy Artists for their Songs, Service, & Important Contributions to Society (CLASSICS) Act, and the bill is now scheduled to be marked up as part of a larger legislative package in the House Judiciary Committee during the week of April 9. According to Representatives Nadler and Issa, the bill aims to resolve “uncertainty over the copyright protections afforded to sound recordings made before 1972 by bringing these recordings into the federal copyright system and ensuring that digital transmissions of both pre- and post-1972 recordings are treated uniformly.” On February 8, 2018, a companion bill was introduced in the Senate, led by Senators Chris Coons (D-Del.) and John Kennedy (R-Louis.). At its core, the CLASSICS Act would take an important step to recognize and protect the creative labors of artists who recorded their songs before 1972, bringing them closer to being on equal footing with artists who recorded their songs after 1972.

The CLASSICS Act would amend Title 17 of the United States Code, adding a Chapter 14 titled “Unauthorized Digital Performance of Pre-1972 Sound Recordings.” Under the proposed language, “[a]nyone who, . . . without the consent of the rights owner, performs publicly, by means of a digital audio transmission, a sound recording fixed on or after January 1, 1923, and before February 15, 1972, shall be subject to the remedies provided in sections 502 through 505 [of the Copyright Act] to the same extent as an infringer of copyright.” In other words, copyright owners of pre-1972 sound recordings would finally be able to stop digital platforms from publicly performing their songs without permission or compensation. This would remedy the current injustice that allows digital platforms to profit from publicly performing hundreds of thousands of pre-1972 sound recordings without paying a penny back to the myriad artists who put their hearts and souls into creating those sounds.

To be clear, the CLASSICS Act does not create a true free market for the digital public performance of pre-1972 sound recordings. Like post-1972 sound recordings, pre-1972 sound recordings would still be subject to the statutory licensing provisions in Section 114 of the Copyright Act. Nonetheless, the leap from no payment at all to payment under the Section 114 statutory licensing provisions is a significant increase for legacy recording artists, and it at least puts them on the same playing field (with respect to digital public performance) as owners of post-1972 sound recordings. Furthermore, not every digital public performance of a sound recording qualifies for the Section 114 statutory license, and in those instances the CLASSICS Act would allow owners of pre-1972 sound recordings to benefit from the same free market that owners of post-1972 sound recordings enjoy.

In addition to creating a cause of action for unauthorized digital public performance of pre-1972 sound recordings, the CLASSICS Act would also preempt “any claim of common law copyright or equivalent right under the laws of any State arising from any digital audio transmission” of a pre-1972 sound recording. The proposed statutory language also ensures that the limitations on remedies available to copyright owners for fair use, uses by libraries, archives, and educational institutions would apply to unauthorized uses of a pre-1972 sound recording. And the proposed statutory language would subject the newly-created cause of action to Section 512 of the Copyright Act and would apply the same statute of limitations applicable to other actions under the Copyright Act.

While the CLASSICS Act would not provide pre-1972 sound recordings with all the same federal protections that apply to post-1972 sound recordings pursuant to Section 106 of the Copyright Act, by creating a federal cause of action for unauthorized digital public performance of pre-1972 sound recordings, the proposed bill would go a long way towards remedying the current unfair treatment of the creative contributions of legacy recording artists.

Conclusion

For too long, Congress and the states have neglected the property rights of recording artists responsible for some of the most celebrated sound recordings in the canon of American music. As digital streaming services flourish in part through the digital public performance of pre-1972 sound recordings, thousands of legacy artists are left uncompensated and unappreciated. The CLASSICS Act represents a significant first step towards recognizing and rewarding the hard work and achievements of these important musicians.

Matthew Barblan is Executive Director of the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property and Assistant Professor of Law at Antonin Scalia Law School, George Mason University

Kevin Madigan is Assistant Director, Development & Research, at the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property

Yesterday, Representative Thomas Massie introduced the Restoring America’s Leadership in Innovation Act of 2018

Yesterday, Representative Thomas Massie introduced the Restoring America’s Leadership in Innovation Act of 2018  One of the oddities of US copyright law is that sound recordings—the way that our favorite songs are captured on media so that we can listen to them over and over again—were not protected under federal law until the early 1970s. Unfortunately, when the federal Copyright Act was finally amended in 1971 to incorporate sound recordings, copyright protection for sound recordings was not applied retroactively. As a result, artists who recorded music before February 15, 1972 (the effective date of the 1971 Sound Recording Amendment) have been unable to use federal copyright law to safeguard their valuable creative contributions to American music.

One of the oddities of US copyright law is that sound recordings—the way that our favorite songs are captured on media so that we can listen to them over and over again—were not protected under federal law until the early 1970s. Unfortunately, when the federal Copyright Act was finally amended in 1971 to incorporate sound recordings, copyright protection for sound recordings was not applied retroactively. As a result, artists who recorded music before February 15, 1972 (the effective date of the 1971 Sound Recording Amendment) have been unable to use federal copyright law to safeguard their valuable creative contributions to American music. Next week, the Copyright Alternative in Small Claims Enforcement (CASE) Act is scheduled for markup before the House Judiciary Committee, promising long-overdue support for small creators and copyright owners in their fight against overwhelming infringement in the digital age. While the bill has bipartisan support and the backing of a wide array of individual creators, artist organizations, and the creative industries, some detractors are now raising questions of constitutionality in an attempt to interfere with the bill’s passage. But the constitutional argument is merely a meritless rhetorical refrain put forward to mask a steadfast resistance by certain companies to any effort to impose accountability for online infringement.

Next week, the Copyright Alternative in Small Claims Enforcement (CASE) Act is scheduled for markup before the House Judiciary Committee, promising long-overdue support for small creators and copyright owners in their fight against overwhelming infringement in the digital age. While the bill has bipartisan support and the backing of a wide array of individual creators, artist organizations, and the creative industries, some detractors are now raising questions of constitutionality in an attempt to interfere with the bill’s passage. But the constitutional argument is merely a meritless rhetorical refrain put forward to mask a steadfast resistance by certain companies to any effort to impose accountability for online infringement. Late last month, a

Late last month, a  Over the past few weeks, widespread criticism has emerged over a superfluous and seemingly partisan effort to override existing copyright law. The target of concern is the American Law Institute’s (ALI) Restatement of the Law, Copyright project which—despite its stated mission to clarify copyright law—has been revealed as an influenced venture that could futher muddle already complex areas of IP law. And with disapproval ranging from the Restatement committee’s own Advisers to the Acting Register of Copyrights, the project’s future is suddenly in doubt.

Over the past few weeks, widespread criticism has emerged over a superfluous and seemingly partisan effort to override existing copyright law. The target of concern is the American Law Institute’s (ALI) Restatement of the Law, Copyright project which—despite its stated mission to clarify copyright law—has been revealed as an influenced venture that could futher muddle already complex areas of IP law. And with disapproval ranging from the Restatement committee’s own Advisers to the Acting Register of Copyrights, the project’s future is suddenly in doubt. Last week, the fifth round of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) negotiations closed in Mexico City with tensions high and

Last week, the fifth round of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) negotiations closed in Mexico City with tensions high and  This month, Congress introduced a bill that would establish a long-discussed small claims court for copyright disputes. The legislation comes after a House Judiciary Committee

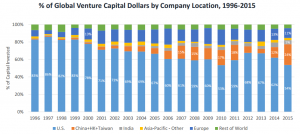

This month, Congress introduced a bill that would establish a long-discussed small claims court for copyright disputes. The legislation comes after a House Judiciary Committee  Venture capital investment in the United States has declined steadily for years, as investors abandon an uncertain domestic climate for more reliable opportunities in foreign countries. In a

Venture capital investment in the United States has declined steadily for years, as investors abandon an uncertain domestic climate for more reliable opportunities in foreign countries. In a  While these numbers are certainly cause for concern, they don’t surprise patent law experts such as former Director of the USPTO, David Kappos, who sees the shift in investments as a natural result of the continuing erosion of IP rights in the US. He warns that “[w]hen investment incentives are reduced, you can expect investment to move elsewhere.” And although a variety of factors are likely contributing to the shift of investments outside of the United States, continuing to weaken our patent system will only aggravate this worrisome trend as VCs increasingly look outside of the US for better returns on their investments. The National Venture Capital Association made this point succinctly in congressional

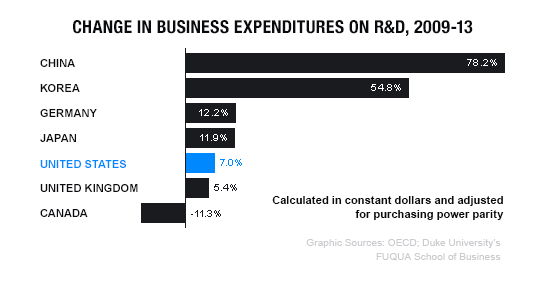

While these numbers are certainly cause for concern, they don’t surprise patent law experts such as former Director of the USPTO, David Kappos, who sees the shift in investments as a natural result of the continuing erosion of IP rights in the US. He warns that “[w]hen investment incentives are reduced, you can expect investment to move elsewhere.” And although a variety of factors are likely contributing to the shift of investments outside of the United States, continuing to weaken our patent system will only aggravate this worrisome trend as VCs increasingly look outside of the US for better returns on their investments. The National Venture Capital Association made this point succinctly in congressional  An extended decline of American R&D investment in innovative industries would be catastrophic, as the value added to the US economy by IP-intensive industries cannot be overstated. A 2016 Department of Commerce

An extended decline of American R&D investment in innovative industries would be catastrophic, as the value added to the US economy by IP-intensive industries cannot be overstated. A 2016 Department of Commerce