Last week, a group of law professors wrote a letter to the acting Librarian of Congress in which they claim that the current FCC proposal to regulate cable video navigation systems does not deprive copyright owners of the exclusive rights guaranteed by the Copyright Act. The letter repeats arguments from response comments they filed along with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), accusing the Copyright Office of misinterpreting the scope of copyright law and once again bringing up Sony v. Universal to insist that copyright owners are overstepping their bounds. Unfortunately, the IP professors’ recurring reliance on Sony is misplaced, as the 30-year-old case does not address the most significant and troubling copyright violations that will result from the FCC’s proposed rules.

Last week, a group of law professors wrote a letter to the acting Librarian of Congress in which they claim that the current FCC proposal to regulate cable video navigation systems does not deprive copyright owners of the exclusive rights guaranteed by the Copyright Act. The letter repeats arguments from response comments they filed along with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), accusing the Copyright Office of misinterpreting the scope of copyright law and once again bringing up Sony v. Universal to insist that copyright owners are overstepping their bounds. Unfortunately, the IP professors’ recurring reliance on Sony is misplaced, as the 30-year-old case does not address the most significant and troubling copyright violations that will result from the FCC’s proposed rules.

In 1984, the Supreme Court in Sony held that recording television shows on a personal VCR was an act of “time-shifting” and therefor did not constitute copyright infringement. The court also ruled that contributory liability requires knowledge, and such knowledge will not be imputed to a defendant based solely on the characteristics or design of a distributed product if that product is “capable of substantial noninfringing uses.” But while this precedent remains good law today, it does not apply to the real concerns creators and copyright owners have with the FCC’s attempt to redistribute their works without authorization.

The FCC’s proposed rules would require pay-TV providers to send copyrighted, licensed TV programs to third parties, even if the transmission would violate the agreements that pay-TV providers carefully negotiated with copyright owners. A different group of IP scholars recently explained to the FCC that by forcing pay-TV providers to exceed the scope of their licenses, the proposed rules effectively create a zero-rate compulsory license and undermine the property rights of creators and copyright owners. The compulsory license would benefit third-party recipients of the TV programs who have no contractual relationship with either the copyright owners or pay-TV providers, depriving creators and copyright owners of the right to license their works on their own terms.

This unauthorized siphoning and redistribution of copyrighted works would occur well before the programming reaches the in-home navigational device, a fact that the authors of the recent letter to the Librarian of Congress either don’t understand, or choose to ignore. Creators and copyright owners are not attempting to “exert control over the market for video receivers,” as the letter suggests. The manufacture and distribution of innovative devices that allow consumers to access the programming to which they subscribe is something that copyright owners and creators embrace, and a thriving market for such devices already exists.

As more consumers resort to cord cutting, countless options have become available in terms of navigational devices and on-demand streaming services. Apple TV, Roku, Nexus Player and Amazon Fire Stick are just a few of the digital media players consumers can choose from, and more advanced devices are always being released. But while the creative community supports the development of these devices, it is the circumvention of existing licenses and disregard for the rights of creators to control their works that has artists and copyright owners worried.

Sony has become a rallying cry for those arguing that copyright owners are attempting to control and stymie the development of new devices and technologies, but these critics neglect the substantial problems presented by the transmission of digital media that Sony couldn’t predict and does not address. In the era of the VCR, there was no Internet over which television was broadcast into the home. In 1984, once a VCR manufacturer sold a unit, they ceased to have any control over the use of the machine. Consumers could use VCRs to record television or play video cassettes as they pleased, and the manufacturer wouldn’t benefit from their activity either way.

The difference with the current navigation device manufacturers is that they will receive copyrighted TV programs to which they’ll have unbridled liberty to repackage and control before sending them to the in-home navigation device. The third-party device manufacturers will not only be able to tamper with the channel placement designed to protect viewer experience and brand value, they will also be able to insert their own advertising into the delivery of the content, reducing pay-tv ad revenue and the value of the license agreements that copyright owners negotiate with pay-TV providers. The FCC’s proposal isn’t really about navigational devices, it’s about the control of creative works and the building of services around TV programs that the FCC plans to distribute to third parties free of any obligation to the owners and creators of those programs.

The authors of the letter conflate two distinct issues, misleading influential decision makers that may not be as well versed in the intricacies of copyright law. By stubbornly comparing the copyright issues surrounding the FCC’s proposed rules to those considered by the Supreme Court in Sony, they craftily try to divert attention away from the real matter at hand: Not what consumers do with the creative works they access in the privacy of their own homes, but how those works are delivered to consumers’ homes in the first place.

It’s curious that after many rounds of back-and-forth comments discussing the FCC’s proposal, proponents of the rules still refuse to address this primary copyright concern that has been continuously raised by creators and copyright owners in corresponding comments, articles, and letters (see also here, here, here, and here). Perhaps the authors of the recent letter simply do not grasp the real implications of the FCC’s plan to seize and redistribute copyrighted content, but given their years of copyright law experience, that is unlikely. More probable is that they recognize the complications inherent in the proposal, but do not have a good answer to the questions raised by the proposal’s critics, so they choose instead to cloud the issue with a similar-sounding but separate issue. But if they truly want to make progress in the set-top box debate and clear the way for copyright compliant navigational devices, they’ll need to do more than fall back on the same, irrelevant arguments.

Malware, short for malicious software, has been used to infiltrate and contaminate computers since the early 1980s. But what began as relatively benign software designed to prank and annoy users has developed into a variety of hostile programs intended to hijack, steal, extort, and attack. Disguised software including computer viruses, worms, trojan horses, ransomware, spyware, adware, and other malicious programs have flooded the Internet, allowing online criminals to profit from illicit activity while inflicting enormous costs on businesses, governments and individual consumers.

Malware, short for malicious software, has been used to infiltrate and contaminate computers since the early 1980s. But what began as relatively benign software designed to prank and annoy users has developed into a variety of hostile programs intended to hijack, steal, extort, and attack. Disguised software including computer viruses, worms, trojan horses, ransomware, spyware, adware, and other malicious programs have flooded the Internet, allowing online criminals to profit from illicit activity while inflicting enormous costs on businesses, governments and individual consumers. Following the Supreme Court’s four decisions on patent eligibility for inventions under

Following the Supreme Court’s four decisions on patent eligibility for inventions under  Earlier this month, a bipartisan group of Senators introduced the Creating and Restoring Equal Access to Equivalent Samples Act (or

Earlier this month, a bipartisan group of Senators introduced the Creating and Restoring Equal Access to Equivalent Samples Act (or  It is common today to hear that it’s simply impossible to search a field of technology to determine whether patents are valid or if there’s even freedom to operate at all. We hear this complaint about the lack of transparency in finding “prior art” in both the patent application process and about existing patents.

It is common today to hear that it’s simply impossible to search a field of technology to determine whether patents are valid or if there’s even freedom to operate at all. We hear this complaint about the lack of transparency in finding “prior art” in both the patent application process and about existing patents.

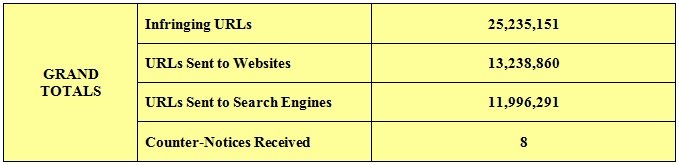

In 2013, CPIP published a policy brief by Professor Bruce Boyden exposing the DMCA notice and takedown system as outdated and in need of reform.

In 2013, CPIP published a policy brief by Professor Bruce Boyden exposing the DMCA notice and takedown system as outdated and in need of reform.

The Second Circuit’s recent opinion in

The Second Circuit’s recent opinion in

It should come as no surprise that popular websites make money by hosting advertisements. Anyone surfing the web has undoubtedly been bombarded with ads when visiting certain sites, and for websites that offer free services or user experiences, advertisements are often the only way to generate revenue. Unfortunately, websites that promote and distribute pirated material also attract advertisers to help fund their illicit enterprises, and despite a recent push for awareness and response to these sites, legitimate advertisers, search engines, and domain name registrars continue to enable them to profit from flagrant copyright infringement.

It should come as no surprise that popular websites make money by hosting advertisements. Anyone surfing the web has undoubtedly been bombarded with ads when visiting certain sites, and for websites that offer free services or user experiences, advertisements are often the only way to generate revenue. Unfortunately, websites that promote and distribute pirated material also attract advertisers to help fund their illicit enterprises, and despite a recent push for awareness and response to these sites, legitimate advertisers, search engines, and domain name registrars continue to enable them to profit from flagrant copyright infringement.