An oil well drilling rig is not an abstract idea. A method of operating an oil well drilling rig is also not an abstract idea. This proposition should be clear to all, but in TDE Petroleum Data Solutions v AKM Enterprise, the Federal Circuit held that a method of operating an oil well drilling rig is directed to the abstract idea of “storing data, receiving data, and using mathematics or a computer to organize that data and generate additional information.”

An oil well drilling rig is not an abstract idea. A method of operating an oil well drilling rig is also not an abstract idea. This proposition should be clear to all, but in TDE Petroleum Data Solutions v AKM Enterprise, the Federal Circuit held that a method of operating an oil well drilling rig is directed to the abstract idea of “storing data, receiving data, and using mathematics or a computer to organize that data and generate additional information.”

Section 101 of the Patent Act has been interpreted to prohibit the patenting of abstract ideas, laws of nature, and natural phenomena. Although recent Supreme Court cases have universally found the patents at issue ineligible, Bilski, Alice and Mayo cite approvingly to a previous Supreme Court case, Diamond v. Diehr, which found a process for molding rubber articles with the aid of a computer to be patent eligible.

Alice and Mayo established a now-famous two-part test to determine whether a patent claims ineligible subject matter. The first step of the Alice/Mayo test asks whether the claim is “directed to” one of the prohibited categories. The second step asks whether the claim involves an “inventive concept” sufficient to confer patent eligibility. The Federal Circuit has applied this test with ruthless efficiency to invalidate patents, although sanity is slowly returning as the court has upheld patents improving computer animation of faces and the preservation of liver cells.

Unfortunately, the Federal Circuit rarely compares the facts of the cases before it to controlling Supreme Court precedent. The clear similarity between the claims to operating an oil well drilling rig in TDE and the claims to curing rubber in Diehr show how far off course the Federal Circuit has veered in interpreting section 101.

In Diehr, the claimed method used a computer to precisely control a rubber molding process. The computer allowed the inventors to measure and recalculate the time to cure the rubber while it was in the mold. At the end of the method, a rubber article was produced. In TDE, the claimed method used a computer to control the drilling of an oil well. The computer permitted the inventors to accurately determine the state of the well operation. Different claims provided for different ends of the method, including adjusting the operation of the drill (claim 30) and selecting the state of the well operation (claim 1).

A side-by-side analysis of representative claims from TDE and Diehr at the bottom of this post shows exactly how similar they are. Each claim recites (1) an industrial process that uses (2) initial data combined with (3) newly collected data that is (4) analyzed to (5) improve the output or operation of the industrial process.

It is worth repeating: in both Diehr and TDE, the claims were directed to an industrial process. The general industrial processes existed previously in the art. Molding rubber using the defined equation was well known. Drilling an oil well with consideration of the state of the well operation was known. The contributions in both Diehr and TDE were the addition of data collection and analysis to improve the operation of the industrial process. Neither portion of the Federal Circuit’s analysis in TDE cites to Diehr, let alone analyzes the obvious similarities between the claims at issue and those found patent eligible by the Supreme Court.

In a single paragraph of analysis regarding step one of the Mayo/Alice test, the Federal Circuit held that claim 1 of the TDE patent was directed to the abstract idea of “storing data, receiving data, and using mathematics or a computer to organize that data and generate additional information.” It completely ignored parts of the claim that required the data to be collected from an oil well drilling operation and to be used for the oil well drilling operation. Of course, ignoring these parts of the claim was required to find that the claim was directed to an abstract idea of data manipulation.

Also taking only a single paragraph, the Federal Circuit’s analysis of Mayo/Alice step two was similarly devoid of engagement with the explicit claim requirements of an oil well drilling operation. Instead, it focused only on what the computer was doing in the process, rather than the process as a whole. Diehr, along with many other cases, explicitly requires that the process be considered as a whole in the section 101 analysis.

The Federal Circuit’s error here is worse than it was in Ariosa v. Sequenom. In Ariosa, the court engaged with the closest factual Supreme Court precedent, although it felt bound by Mayo to find the claims ineligible. However, the court in TDE completely ignored and disregarded Diehr, the Supreme Court case that aligns in both law and fact with the claims at issue. Had the court analyzed or considered Diehr, it is likely the outcome would have been different.

To the extent that one asserts the final method of utilizing the data distinguished claim 1 in Diehr from claim 1 in TDE, dependent claim 30 of the patent at issue in TDE cured this defect. Claim 30 recites: “[t]he method of claim 1, further comprising using the state of the well operation to evaluate parameters and provide control for the well operation.” (emphasis added). Thus, the patent in TDE explicitly claimed the actual operation of the industrial machinery, just as the claim in Diehr.

The Federal Circuit stated that it was not considering separately the remaining claims of the patent, ostensibly because TDE did not “distinguish those claims from representative claim 1.” On the contrary, TDE argued claim 30 and related claims separately on precisely the ground that claim 30 “closed [the] loop” and required control of the well.

At this point, it is clear that neither the Federal Circuit nor the Supreme Court are going to step in to fix the wayward path of patent eligibility law. It will therefore be up to Congress to affirm what should be apparent to all: an oil rig is not an abstract idea.

| Diehr – Claim 1* (US Application No. 05/602,463) | TDE – Claim 1 (US Patent No. 6,892,812) | Analysis | |

| 1 – Preamble | A method of operating a rubber-molding press for precision molded compounds with the aid of a digital computer, comprising: | An automated method for determining the state of a well operation, comprising: | Both claims are directed to industrial processes where the underlying process (rubber molding or oil well drilling) existed prior to the invention |

| 2 – Initial Data | providing said computer with a database for said press, including at least,

natural logarithm conversion data (ln), the activation energy constant (C) unique to each batch of said compound being molded, and a constant (x) dependent upon the geometry of the particular mold of the press, |

storing a plurality of states for a well operation; | Both claims require data to be provided prior to operation of the method to interpret data collected. |

| 3 – New Data Collection | initiating an interval timer in said computer upon the closure of the press for monitoring the elapsed time of said closure,

constantly determining the temperature (Z) of the mold at a location closely adjacent to the mold cavity in the press during molding, constantly providing the computer with the temperature (Z), |

receiving mechanical and hydraulic data reported for the well operation from a plurality of systems; | Both claims require collecting data from sources that are specific to the machinery being operated. Therefore, both claims require specific machinery, not just a general purpose computer. |

| 4 – Data Analysis | repetitively calculating in the computer, at frequent intervals during each cure, the Arrhenius equation for reaction time during the cure, which is

ln v = CZ + x where v is the total required cure time, repetitively comparing in the computer at said frequent intervals during the cure each said calculation of the total required cure time calculated with the Arrhenius equation and said elapsed time, and |

and determining that at least some of the data is valid by comparing the at least some of the data to at least one limit, the at least one limit indicative of a threshold at which the at least some of the data do not accurately represent the mechanical or hydraulic condition purportedly represented by the at least some of the data; and when the at least some of the data are valid, based on the mechanical and hydraulic data, | Both claims analyze the data.

Although not apparent on the face of the claims, the underlying data analysis existed in the art for both claims. The Arrhenius equation was well known. Validating well drilling data against a limit was known in the art although its usefulness was disputed. |

| 5 – Utilizing the Data | opening the press automatically when a said comparison indicates equivalence. | automatically selecting one of the states as the state of the well operation. | Both claims use the data generated in the industrial process. Selecting an individual state of a well operation in a necessary component of operating the well. |

*Claim 1 is representative for both the application in Diehr and the patent in TDE.

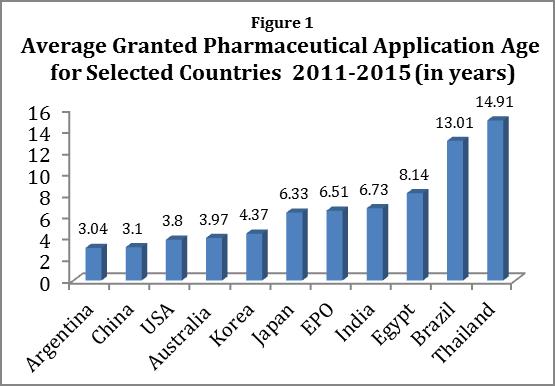

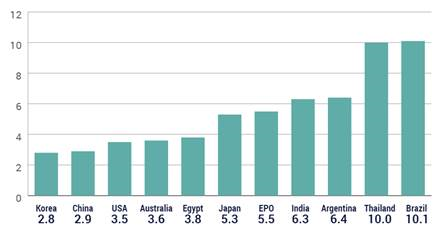

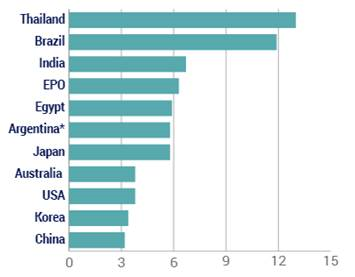

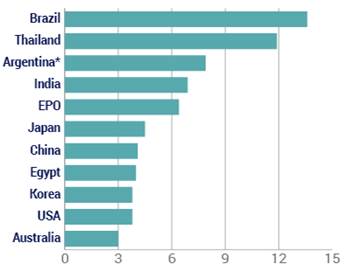

Why are some of the biggest fights about patent policy almost pointless in some places? Because in many countries, including some of the world’s most important emerging economies, it takes so long to get patents that the rights have little meaning.

Why are some of the biggest fights about patent policy almost pointless in some places? Because in many countries, including some of the world’s most important emerging economies, it takes so long to get patents that the rights have little meaning.

Last week, YouTube celebrity (yes, that’s a thing now) Olajide “JJ” Olatunji posted an expletive-filled

Last week, YouTube celebrity (yes, that’s a thing now) Olajide “JJ” Olatunji posted an expletive-filled  The Second Circuit handed down an

The Second Circuit handed down an  Scalia Law’s Arts & Entertainment Advocacy Clinic and Washington Area Lawyers for the Arts (WALA) are hosting a Copyright Clinic and Panel on the evening of Tuesday, November 1st, 2016, at the law school.

Scalia Law’s Arts & Entertainment Advocacy Clinic and Washington Area Lawyers for the Arts (WALA) are hosting a Copyright Clinic and Panel on the evening of Tuesday, November 1st, 2016, at the law school. The FTC released its

The FTC released its  Earlier this month, a federal judge in the Southern District of New York issued an

Earlier this month, a federal judge in the Southern District of New York issued an  In a

In a