Led by Prof. Adam Mossoff and C-IP2 Senior Fellow and Senior Scholar Prof. Jonathan M. Barnett, twenty-five law professors, economists, and former United States Government officials—including C-IP2 Advisory Board members the Honorable Andrei Iancu, the Honorable David J. Kappos, the Honorable Paul Michel, and the Honorable Randall R. Rader; Faculty Director Prof. Sean M. O’Connor; Senior Scholar Prof. Kristen Osenga; and Scholar Dr. Bowman Heiden—submitted a letter in response to a “call for evidence” on the licensing, litigation, and remedies of standard-essential patents (SEPs). The response discusses core functions of SEPs in the wireless ecosystem, the lack of evidence of Patent Holdup and Royalty Stacking, assumptions about SEPs and Market Power, the importance of the potential for injunctive relief even for FRAND, levels of licensing, and SEP licensing in SME markets. The letter is available here on SSRN.

The following post comes from Laura Mertens and is cross-posted here from Mason’s Center for the Arts website with permission.

Known for fearless musical exploration and beautifully blurring lines between genres, composer Maria Schneider has earned seven GRAMMY Awards across the realms of jazz, classical, and even her work with David Bowie. Serving as Mason Artist-in-Residence this April, she led a powerful series of events across Fairfax and Arlington campuses with students, faculty, staff, and community members. Launched during the 2019-2020 season, the Mason Artist-in-Residence program connects artists appearing at the Center for the Arts in Fairfax and the Hylton Performing Arts Center in Manassas with communities throughout Northern Virginia in a variety of activities for diverse audiences, creating opportunities for transformational experiences.

Through discussions, open rehearsals, and a culminating concert, the residency helped reinforce how Schneider became a groundbreaking visionary in the field. Events began with Beyond the Notes with Maria Schneider: A Conversation about Respecting Artist Rights, held on April 14 in Van Metre Hall on Mason’s Arlington Campus, and co-hosted by Mason’s Center for Intellectual Property x Innovation Policy (C-IP2) and Arts Management Program. George Mason University Antonin Scalia Law School Professor and Arts & Entertainment Advocacy Clinic Director Sandra Aistars moderated the conversation with Schneider, which was also streamed live to an audience including individuals joining in from Ghana, Nigeria, the UK, and India.

Aistars said, “Maria Schneider seamlessly blends her art and her advocacy. Her skill in both musical composition and arts advocacy is that she moves us to hear what she shows us, often through unconventional means—be it the beauty of the natural world, the poignancy of a shared moment between friends, or the artist’s struggle to preserve dignity and rights in the digital world. She is also fierce. We need artists like Maria who are not afraid to remind corporations, fans, and artists alike to behave ethically towards one another if they hope to maintain a healthy music ecosystem that will sustain the next generations of artists and audiences.”

Schneider discussed her expansive approach to big band instrumentation, noting that the ensemble is a “solid, powerful medium,” but that she loves to push its boundaries to explore further, asking, “How can I stretch this instrumentation?” Weaving together recorded clips of music and conversation, the Thursday event began with a recording of her work “Cerulean Sky,” which combined flute, muted trumpet—and birdsong. She acknowledged, “It doesn’t sound much like a big band, but it is.”

The LA Times has said, “…Schneider’s [music] reaches toward a significant new level of imagination, making hers the first truly novel approach to big jazz band composition of the new century.” She explained to the crowd, “I’ve always been a composer who wants to explore new ground.” She credits her mentors with helping her hone her unique compositional voice, including jazz pianist/arranger/composer/bandleader Gil Evans and the “ethereal quality” of his work, and Bob Brookmeyer, her composition teacher who saw her natural inclination towards jazz despite all her classical training, and encouraged her to go chart for big bands. Of her recent work, the 2021 Pulitzer Prize finalist piece Data Lords, NPR said, “This is music of extravagant mastery, and it comes imbued with a spirit of risk.”

Schneider’s risk-taking has also helped blaze a trail for the trend of crowdfunding, as one of the first artists to sign with ArtistShare, today widely recognized as an early precursor to websites like KickStarter, IndieGoGo, and PledgeMusic. She says ArtistShare founder Brian Camelio explained to her, “One thing you can’t fileshare is the creative process.” She notes that she documents her process on the platform through internet-exclusive streaming videos, sketches of her scores, and photos from rehearsals and concerts. “You can announce you’re doing a project, feature interviews with players, allow fans to become closer to the music. . . I like that I don’t have any anonymous sales.” Releasing her “Concert in the Garden” album on ArtistShare in 2004, she became the first artist to win a GRAMMY Award for an album not available in retail stores. Schneider exhorted artists in the room to “Never give up creative control of your work.”

Attendee and second-year law student Brianna Marie Christenson, a member of Prof. Aistars’ Arts and Entertainment clinic who has worked as a business manager and plans to go into copyright law, said, “Maria Schneider shows creatives how to use a technology built to serve the audience and not the artist, like music streaming platforms, work for both artist and fan. Her use of online platforms to find new fans and bring them to her own site for sale of her repertoire is a brilliant way to handle having a niche audience while trying to recoup on albums. . . .Her leadership in use of crowdfunding is something artists replicate en masse now.”

Schneider has also testified about digital rights before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Intellectual Property, participated in round-tables for the United States Copyright Office, given commentary on CNN, and filed a class-action lawsuit against YouTube.

Mason Alumnus and Assistant Professor of Jazz Studies John M. Kocur, a saxophonist who also rehearsed for six hours with Schneider and played on the April 16 concert, notes, “Maria Schneider valiantly defends of the rights of musicians against corporate interests. She makes music for social advocacy and advocates for musical justice. The core of her message is that our intellectual property is valuable, and we ought to guard it carefully or our entire culture will suffer.”

While embracing technology to allow artists to be more independent, Schneider also emphasized the need to unplug, telling Mason Jazz Ensemble students in an open rehearsal/Q&A on April 15 at the Center for the Arts: “I don’t believe you can be a great artist unless you give yourself space. Leave your phone at home. Allow yourself to get bored. That’s when you start to imagine things. Dream it up. Make something. You will come through your music.”

Schneider’s rehearsal with the Mason Jazz Ensemble students and additional sessions with the professional Metropolitan Jazz Orchestra culminated in the galvanizing April 16 concert at the Center, with Schneider conducting her own works performed by the ensembles.

Featured Mason Artists-in-Residence in the newly announced 2022/2023 Center for the Arts season, will include Nrityagram Dance Ensemble, Indigenous Enterprise, and the launch of a three-year residency with Silkroad Ensemble. Learn more about the Mason Artist-in-Residence program at cfa.gmu.edu/about/artists-residence.

Greetings from C-IP2 Faculty Director Sean O’Connor

Greetings from C-IP2 Faculty Director Sean O’Connor

As we move further into spring of 2022, we are simultaneously emerging––gradually and hopefully––from the global health crisis of these past two years. In-person gatherings and events are steadily resuming in the Washington, D.C., area and in many places around the world, and it’s wonderful to share the same spaces once again with friends and colleagues, old and new. Early last December, C-IP2 held our first large-scale in-person event since 2020 with our hybrid conference on Intellectual Property and Innovation Policy for 5G and the Internet of Things. Excepting January 2022’s Edison Fellowship meeting and precautions taken against the Omicron variant, we have been moving ahead with primarily in-person programming for 2022, and we hope you will keep an eye on our website and email communications for opportunities to join us and engage with us. In the meantime, our Spring 2022 Progress Report below (spanning December 2021 through February 2022) will catch you up on the activities and scholarship of C-IP2 and affiliates in recent months, and we continue to wish you good health in the months to come.

C-IP2 Hosted & Co-Hosted Events

Academic ConferenceOn December 2-3, 2021, C-IP2 hosted an academic conference on 5G and Beyond: Intellectual Property and Competition Policy in the Internet of Things. The event was both held in person and livestreamed from George Mason University, Antonin Scalia Law School, and featured as speakers many of the contributors for the upcoming corresponding book, 5G and Beyond: Intellectual Property and Competition Policy in the Internet of Things, which is being co-edited by Professors Jonathan Barnett and Sean O’Connor and has been accepted for publication by Cambridge University Press (Forthcoming 2022). Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy FellowshipOn January 20-21, 2022, C-IP2 hosted the third and final meeting of the 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship. The Edison Fellows presented substantially revised drafts of their research papers and received feedback from Distinguished Senior Commentators and other Fellows. The plan is for Fellows to submit their final papers to journals for the March submission period.

News & Speaking Engagements

We are pleased to welcome and announce the scholars and practitioners who have joined C-IP2 over the course of December 2021 through February 2022: Tun-Jen Chiang as a Senior Scholar; Gregory Dolin, John Liddicoat, and Amy Semet as Scholars; and Theo Cheng, Stephanie Semler, and Eric Solovy as Practitioners in Residence. The Antonin Scalia Law School winter graduation was held on December 16, 2021, at Eagle Bank Arena in Fairfax, VA. C-IP2’s December 2021 5G conference was mentioned by ThinkBRG, which noted BRG Executive Chairman David J. Teece’s participation in a panel on “Global Differences in Antitrust Treatment of SEPs and SSOs.” C-IP2 was mentioned in a February story on Broadway World, highlighting their upcoming April 2022 event with GRAMMY Award-winning composer Maria Schneider, co-hosted with George Mason University Center for the Arts. In February, Jeffrey E. Depp—a 2022-2023 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellow with C-IP2 and PhD student at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public and International Affairs—received the Volunteer of the Year Award from AUTM. Professor Sean M. O’Connor posted his book chapter “AI Replication of Musical Styles Points the Way to an Exclusive Rights Regime,” which is part of the upcoming book Research Handbook on Intellectual Property and Artificial Intelligence (Edward Elgar 2022 Forthcoming), edited by Dr. Ryan Abbott. Sandra Aistars (C-IP2 Senior Fellow for Copyright Research and Policy & Senior Scholar; Founding Director, Arts & Entertainment Advocacy Clinic; Clinical Professor of Law, George Mason University Antonin Scalia Law School)

-

- Served as a commentator at the University of Akron IP Scholars Forum on December 9-10, 2021

- Scholarly contributions to advancing copyright law cited in a December 16 IPWatchdog article on The Year in Copyright: From Google v. Oracle to the Takings Clause by Devlin Hartline, Legal Fellow at the Hudson Institute’s Forum for Intellectual Property in Washington, D.C. (Items cited include: March 27, 2018, organizing and drafting IP scholars briefing in a decade of briefing culminating before the Supreme Court in Google LLC v Oracle America, Inc. opinion; a May 9, 2019, IPWatchdog article with the Copyright Alliance’s Kevin Madigan on the CASE Act; 2018 scholarly article on a small copyright claims tribunal; and research and analysis cited in the August 2021 U.S. Copyright Office’s Copyright and State Sovereign Immunity report)

- On January 13, participated in a Copyright Alliance meeting to discuss the December 30 CASE Act notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM)

- In February, along with the Arts & Entertainment Advocacy Clinic, filed initial and reply comments by IP scholars regarding Law Student and clinic participation in representation of individuals and small businesses before the CCB pursuant to the CASE Act

- Quoted in a February 11 article on The Verge, “Artists Are Playing Takedown Whack-A-Mole To Fight Counterfeit Merch”

Jonathan Barnett (C-IP2 Senior Fellow for Innovation Policy & Senior Scholar; Torrey H. Webb Professor of Law, USC Gould School of Law)

-

- Helped to organize and participated in C-IP2’s December conference on 5G and IP as a co-editor with Professor Sean O’Connor on the upcoming corresponding book, 5G and Beyond: Intellectual Property and Competition Policy in the Internet of Things

- On January 19, presented at a webinar hosted by the 4iP Council (Jan. 20, 2022), “Solution in Search of a Problem: The Economic Case Against Licensing Negotiation Groups in the Internet of Things”

- On February 4, co-authored and submitted comments with fellow scholars of law, economics, and business regarding the Draft USPTO, NIST, & DOJ Policy Statement on Licensing Negotiations and Remedies for Standard Essential Patents Subject to Voluntary F/RAND Commitments

- Mentioned in a February 7 Foss Patents blogpost, “In its replies to Apple’s public interest statements, Ericsson points the ITC to Apple’s 30% app tax and market definition in Epic Games case”

Chief Judge Susan G. Braden (Court of Federal Claims (Ret.); C-IP2 Jurist in Residence)

-

- On December 8, attended the USPTO Private Patent Advisory Committee Meeting on Congressional Legislation

- On January 19, took part in Designated Chair of Artificial Intelligence Tools and Information Technology Subcommittee, USPTO Private Patent Advisory Committee

- On January 27, joined Meeting with Matthew Such, Group Leader, Patent Product Line Lead, Office of Patent Information Management, USPTO re AI priorities for 2022

- On January 31, completed Working Draft of “Section 1498 (a): NOT A RX FOR LOWER PHARMA PRICES” (out for academic comment), which was co-authored with Joshua Kresh, C-IP2 Managing Director

- In February, was appointed to the 2022 National Vaccine Law Conference Committee

- On February 8, attended the USPTO Private Patent Advisory Committee Innovation, Expansion, and Outreach Subcommittee Meeting

- On February 9, attended the Executive Session of USPTO Private Patent Advisory Committee

- On February 10, attended the USPTO Private Patent Advisory Artificial Intelligence Tools and Information Technology Subcommittee Meeting

- On February 25, met with the Lead Business Development SAS US Alliances/Channels Team

Terrica Carrington (C-IP2 Practitioner in Residence; VP, Legal Policy and Copyright Counsel, Copyright Alliance)

-

- Helped organize and co-host a December 6 event (sponsored by the Copyright Alliance and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Global Innovation Policy Center and Equality of Opportunity Initiative) titled “A Conversation on Diversity and Inclusion in Copyright,” where speakers and attendees discussed how to increase participation from underrepresented communities in the copyright sector industries and professions

- Nominated in January 2022 for the G. Hamilton Loeb Award for Pro Bono Excellence in recognition of her work to support the arts

- Quoted in a January 11 article by Franklin Graves on Tubefilter, “Here Are The Legal Issues Affecting Content Creators in 2022”

Theo Cheng (C-IP2 Practitioner in Residence; Arbitrator and Mediator, ADR Office of Theo Cheng LLC; Adjunct Professor, New York Law School)

-

- In December, his article “Conducting Remote Mediations During the Pandemic” was published in the New York State Bar Association Trial Lawyers Digest

- On December 22, gave a two-hour presentation on “Diversity, Implicit Bias & Cross-Cultural Skills in ADR” to the court staff at the Supreme Court of New York, Appellate Division, Second Department

- Joined C-IP2 as a Practitioner in Residence in January

- On January 11, was a co-presenter on a program entitled “Nonparty Discovery in U.S. Arbitrations: The Legal Challenges & Differences from Litigation” for the New York State Bar Association that was sponsored by the Dispute Resolution Section Domestic Arbitration Committee

- On February 23, moderated a panel entitled “Diversity, Inclusion and Elimination of Bias in Evidentiary Analysis and Decision Making.” The panel was part of an all-day program held by the New York County Lawyers Association for New York’s Part 137 Fee Disputes and Conciliation Arbitration Training Program

Tun-Jen Chiang (C-IP2 Senior Scholar; Professor of Law, George Mason University, Antonin Scalia Law School)

-

- Joined C-IP2 as a Senior Scholar in January

Eric Claeys (C-IP2 Senior Fellow for Scholarly Initiatives & Senior Scholar; Professor of Law, George Mason University Antonin Scalia Law School)

-

- On January 20-23, co-organized and participated in the third and final meeting of the 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship

Gregory Dolin (C-IP2 Scholar; Associate Professor of Law, University of Baltimore School of Law)

-

- Joined C-IP2 as a Scholar in January

John F. Duffy (C-IP2 Senior Scholar; Samuel H. McCoy II Professor of Law and Paul G. Mahoney Research Professor of Law, University of Virginia School of Law)

-

- On January 20-21, served as a Distinguished Senior Commentator during the third and final meeting of the 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship

Tabrez Ebrahim (C-IP2 Scholar; Associate Professor, California Western School of Law)

-

- Professor Ebrahim will be joining Lewis & Clark Law School and the Center for Business Law and Innovation [Lewis & Clark Law School, Leiter Law School] this coming Fall 2022

- In January, gave a presentation entitled “Datafication & Data Governance at the Patent Office” at the virtual AALS Annual Meeting: New Voices in Intellectual Property Law Scholarship

- Joined a research project with the University of Arizona’s Center for Quantum Networks (January 2022-Present) as a Fellow (Thrust 4: Societal Impact of the Quantum Internet)

- On February 4, presented on a panel entitled Data Privacy & Democracy at the Lewis & Clark Law School’s 3rd Annual Data Privacy Forum

- On February 19, presented a draft article entitled An Information Theory of Data Governance at the Patent Office as part of the 19th Works in Progress for Intellectual Property Scholars Colloquium (WIPIP 2022), co-hosted by St. Louis University School of Law and University of Missouri School of Law

Jon M. Garon (C-IP2 Senior Scholar; Professor of Law and Director of the Intellectual Property, Cybersecurity, and Technology Law program, Nova Southeastern University Shepard Broad College of Law)

-

- In December, served as Moderator and Program Coordinator for Business Law Basics – Lost in Tokenization: Legal Implications of Non-Fungible Tokens on Finance, Art, Property, and Culture, American Bar Association Business Law Section [This 90-minute CLE is free-on-demand for all ABA Business Law Section members]

- In December, developed a CLE program which he moderated entitled Business Law Basics – Lost in Tokenization: Legal Implications of Non-Fungible Tokens on Finance, Art, Property, and Culture, American Bar Association Business Law Section

- In January, presented Legal Strategies for the Metaverse and the Evolving Media Landscape (American Bar Association, Business Law Section Cyberspace Law Committee, Cyberspace Law Institute)

- Has contracted to publish a new book entitled Teaching and Learning in the Metaverse: Using Online Platforms, Games, NFTs, and Blockchain in Education with Rowman & Littlefield (2023)

- On February 22, gave a virtual presentation on Understanding the Evolving Media Landscape for Nova Southeastern University’s Lifelong Learning Institute

- On February 22, received a “Top Ten” Download from SSRN.com for six electric journals. His draft article, Legal Implications of a Ubiquitous Metaverse and a Web3 Future, is available at SSRN

- Latest book, Parenting for the Digital Generation – The Parent’s Guide to Digital Education and the Online Environment (Rowman & Littlefield 2022), is available for order both in stores and online [Rowman & Littlefield, Amazon, Barnes & Noble]

Christopher Holman (C-IP2 Senior Fellow for Life Sciences & Senior Scholar; Professor of Law, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law)

-

- Spoke at the FDA-PTO Roundtable at the George Washington University Law School on December 21

- On January 20-21, served as a Distinguished Senior Commentator during the third and final meeting of the 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship

- On January 21, spoke as a panelist at the FDA-PTO Roundtable on patents and pharmaceutical pricing at the George Washington University Law School

- On January 28, spoke on a panel entitled “FDA and Patents? FDA’s Letter to the USPTO and Possible Next Steps” as part of the Food, Drug & Cosmetic Law Section at the New York State Bar Association Annual Meeting

- On February 18, presented a draft article entitled Evolution of the Antibody Patent as part of the 19th Works in Progress for Intellectual Property Scholars Colloquium (WIPIP 2022), co-hosted by St. Louis University School of Law and University of Missouri School of Law

Camilla A. Hrdy (C-IP2 Scholar; Research Professor in Intellectual Property Law, University of Akron School of Law)

-

- Article “Abandoning Trade Secrets” (with Mark A. Lemley), 72 Stan. L. Rev. 1 (2021) was cited by a U.S. District court in Providence Title Co. v. Truly Title, Inc., et al., No. 4:21-CV-147-SDJ, 2021 WL 2701238 (E.D. Tex. July 1, 2021)

- Article “The Trade Secrecy Standard for Prior Art” (with Sharon K. Sandeen), 70 Am. U. L. Rev. 1269 (2021) was selected as the featured patent law article for American University Law Review’s annual Federal Circuit Symposium Issue

- On December 10, new article, “The Value in Secrecy,” was identified as one of the best works of recent scholarship relating to intellectual property law by Jotwell: The Journal of Things We Like (Lots) [SSRN]

- On December 13-14, attended The Sedona Conference WG12 Annual Meeting 2021 in Phoenix, AZ. Prof. Hrdy is a Member of Brainstorming Group on “What Can and Cannot Be a Protectable Trade Secret?”

- Authored a January 12 post on the Written Description blog entitled “Jessica Litman: Who Cares What Edward Rogers Thought About Trademark Law?”

- Mentioned in a February 10 Law360 article, “Hytera Indictment May Set New Path For Trade Secrets Cases”

Dmitry Karshtedt (C-IP2 Scholar; Associate Professor of Law, The George Washington University Law School)

-

- Co-authored a December 22 amicus brief on Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi

- Quoted in a January 12 BloombergLaw article by Ian Lopez, Hikma Drug Label Win Still Leaves Generics on Hook for Liability

- Spoke at the FDA-PTO Roundtable at the George Washington University Law School on January 21

- Quoted in a January 27 Law360 article by Ryan David, Breyer’s Rulings Shaped By Wariness Of Intellectual Property

- On February 18, presented a draft article entitled An Information Theory of Data Governance at the Patent Office as part of the 19th Works in Progress for Intellectual Property Scholars Colloquium (WIPIP 2022), co-hosted by St. Louis University School of Law and University of Missouri School of Law

- Placed in-progress paper, Pharmaceutical Patents and Adversarial Examination in The George Washington Law Review, forthcoming 2023

Hon. Prof. F. Scott Kieff (C-IP2 Senior Scholar; Fred C. Stevenson Research Professor, The George Washington University Law School)

-

- Gave the keynote address at C-IP2’s December conference on 5G and IP as a contributor to the upcoming corresponding book, 5G and Beyond: Intellectual Property and Competition Policy in the Internet of Things

Dr. John Liddicoat (C-IP2 Scholar; Senior Research Associate and Affiliated Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Cambridge)

-

- Joined C-IP2 as a Scholar in January 2022

- On January 20-21, participated as an Edison Fellow during the third and final meeting of the 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship

- Chaired a February 10 seminar hosted by Cambridge University’s Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Law (CIPIL), presented by speaker David Webb (Herbert Smith Freehills), and entitled FRAND: Where are we: And where are we going? (read more here and click here to view the recording on YouTube)

Joshua Kresh (C-IP2 Managing Director)

-

- On January 20-21, co-organized and participated in the third and final meeting of the 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship

- On January 31, completed Working Draft of “Section 1498 (a): NOT A RX FOR LOWER PHARMA PRICES” (out for academic comment), which was co-authored with Judge Susan G. Braden

Daryl Lim (C-IP2 Senior Scholar; Professor of Law and the Director of the Center for Intellectual Property (IP), Information & Privacy Law, University of Illinois Chicago School of Law)

-

- On December 9, was a Discussant during the virtual Fordham IP Institute Global IP Roundtable

- On December 14, was a Moderator during the virtual 4th edition of the Paris conference on Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) and FRAND (Session 1)

- Was a Speaker for “Can Computational Antitrust Succeed?” during the virtual Computational Antitrust: Exploring Antitrust 3.0 conference at the Stanford Center for Legal Informatics, December 13-15, 2021

- On December 17, was a Discussant/Commentator at the Centre for Financial Regulation and Economic Development (CFRED) at the Chinese University of Hong Kong Law (CUHK Law) and the Center for Law and Intellectual Property at Texas A&M University School of Law’s workshop on Anti-suit Injunctions and FRAND Litigation in China

- In a December 28 IPWatchdog piece, provided his choices for “the biggest moments in IP for 2021”

- Mentioned in a February 3 article by Penn State, “Penn State Dickinson Law announce new resident faculty appointment”

- On February 8, spoke on “What can Copyright Law Learn from Design Law?” during the virtual ABA-IPL Design Rights Committee Fireside Chat

Hina Mehta (C-IP2 Practitioner in Residence; Director, Office of Technology Transfer, George Mason University)

-

- Attended the February 20-23 Association of University Technology Managers Conference where she served as instructor for a half day professional development course on Negotiations

Emily Michiko Morris (C-IP2 Senior for Life Sciences and Scholar; C-IP2 2021-2022 Edison Fellow; David L. Brennan Endowed Chair, Associate Professor, and Associate Director of the Center for Intellectual Property Law & Technology, University of Akron School of Law)

-

- Spoke at the FDA-PTO Roundtable at the George Washington University Law School on December 21

- On January 20-21, participated as an Edison Fellow during the third and final meeting of the 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship

- Spoke at the FDA-PTO Roundtable at the George Washington University Law School on January 21

Sean M. O’Connor (C-IP2 Faculty Director; Faculty Director, Innovation Law Clinic; Professor of Law, George Mason University Antonin Scalia Law School)

-

- On December 1, gave an LLC presentation with Antonin Scalia Law School’s Dean Ken Randall to George Mason University’s Green Machine

- Helped to organize and spoke at C-IP2’s December conference on 5G and IP as a co-editor with Professor Jonathan Barnett on the upcoming corresponding book, 5G and Beyond: Intellectual Property and Competition Policy in the Internet of Things

- On January 20-21, co-organized and participated in the third and final meeting of the 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship

- On January 23, gave a virtual Texas A&M IP Management talk

- On January 31, spoke at a seminar as part of the Loyola Law School’s Intellectual Property and Information Law Speaker Series at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, California

Kristen Jakobsen Osenga (C-IP2 Senior Scholar; Austin E. Owen Research Scholar and Professor of Law, University of Richmond School of Law)

-

- Spoke at C-IP2’s December conference on 5G and IP as a contributor to the upcoming corresponding book, 5G and Beyond: Intellectual Property and Competition Policy in the Internet of Things

- On January 5, served as a senior commentator in an IP Works in Progress session for a paper by Tabrez Ebrahim at the Association of American Law Schools (AALS) Annual Meeting

- On January 7, served a moderator for a Federalist Society Works in Progress Mini-Conference panel

- On January 25, participated in a Hudson Institute roundtable about national security & IP

- On February 4, was cited in and submitted comments with fellow scholars of law, economics, and business regarding the Draft USPTO, NIST, & DOJ Policy Statement on Licensing Negotiations and Remedies for Standard Essential Patents Subject to Voluntary F/RAND Commitments

- Filed a brief with Professors Jonathan Barnett, Richard Epstein, and Adam Mossoff to the International Trade Commission about the importance of exclusionary order for SEPs and public interest in the Ericsson v. Apple case. Filing was mentioned in a February 7 Foss Patents blogpost, “In its replies to Apple’s public interest statements, Ericsson points the ITC to Apple’s 30% app tax and market definition in Epic Games case”

- Spoke on a February 16 panel entitled, “Theory to Doctrine: Should Specific Antitrust Doctrines or Cases Be Revisited in the Digital Age?” The panel was part of the Big Tech and Antitrust Conference, and sponsored by the Gibbons Institute of Law, Science & Technology, and the Institute for Privacy Protection at Seton Hall Law School.

- On February 18, participated in the 15th Annual Evil Twin Debate against Jorge Contreras (Presidential Scholar and Professor of Law, University of Utah S.J. Quinney College of Law). Profs. Contreras and Osenga debated “Efficient Infringement: Awful or Awesome?”

Mark F. Schultz (C-IP2 Senior Scholar; Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company Chair in Intellectual Property Law, University of Akron School of Law; Director, Center for Intellectual Property Law and Technology)

-

- On December 2, participated in the Global Trade and Innovation Policy Alliance’s 2021 Global Trade and Innovation Policy Alliance Annual Summit in Washington, D.C., where he spoke on trends in national regulation of Video on Demand Streaming Services worldwide

- On December 16, spoke in a MacDonald-Laurier Institute (Canada) webinar regarding the appropriate regulatory and IP policies to avoid supply chain disruptions in the manufacturing and distribution of vaccines for the next pandemic

- Spoke in January 2022 at an event hosted by UC Berkeley and the Sunwater Institute on empirical methods for measuring the strength of national IP systems

- On January 20-21, served as a Distinguished Senior Commentator during the third and final meeting of the 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship

- On January 28-29, participated as a commentator at the Three Rivers IP Colloquium

- On February 8, spoke at a webinar entitled “Extending Bio-manufacturing Networks in Emerging Regions,” sponsored by Bobab (an Africa-based NGO) and the Innovation Council (a Swiss NGO), about creating an enabling environment for manufacturing vaccines and therapeutics in Africa and other emerging regions

- Quoted in a February 11 article on The Verge, “Artists Are Playing Takedown Whack-A-Mole To Fight Counterfeit Merch.”

- On February 18, spoke at an online roundtable sponsored by the National Law University of Bangalore and the Government of India about drafting a trade secret statute for India

Amy Semet (C-IP2 Scholar; Associate Professor, University at Buffalo School of Law)

-

- Joined C-IP2 as a Scholar in January 2022

Stephanie M. Semler (C-IP2 Practitioner in Residence; Adjunct Professor, George Mason University, Antonin Scalia Law School; Associate Attorney, Venable LLP; Supervising Attorney, Arts & Entertainment Advocacy Clinic)

-

- Joined C-IP2 as a Practitioner in Residence in January 2022

Eric M. Solovy (C-IP2 Practitioner in Residence; Partner, Sidley Austin LLP)

-

- In February, joined C-IP2 as a Practitioner in Residence

Scholarship & Other Writings

Jonathan Barnett, Does the Market Know Something the FTC Doesn’t?, Truth on the Market (February 10, 2022) Jonathan Barnett, The Economic Case Against Licensing Negotiation Groups in the Internet of Things (January 10, 2022). USC CLASS Research Paper Series No. CLASS22-1, USC Legal Studies Research Paper Series No. 22-1 [SSRN] Jonathan Barnett, How Not to Promote US Innovation (February 18, 2022), Truth on the Market Jonathan Barnett, Time To Nix Antitrust Policies That Fueled Blocked Nvidia Deal (February 10, 2022), Law360 Terrica Carrington, Copyright Office Activities in 2021: A Year In Review, Copyright Alliance (Jan. 11, 2022) Jon M. Garon, Book Chapter, “Legal Issues for Database Protection in the US and Abroad,” in Bioinformatics Law: Legal Issues for Computational Biology in the Post-Genome Era, ed. Jorge Contreras (Edward Elgar Publishing 2d Ed. 2021) (December 2021) Thomas Grant and Scott Kieff, 3 Safe Passages To Avoid Sanctions Double Binds, Law360 (February 9, 2022) Christopher M. Holman, Is the Chemical Genus Claim Really “Dead” at the Federal Circuit?: Part I, 41 Biotechnology Law Report 4 (2022) Camilla Hrdy, Jessica Litman: Who Cares What Edward Rogers Thought About Trademark Law?, Written Description (Jan. 12, 2022) Camilla Alexandra Hrdy, The Value in Secrecy (August 2, 2021). Fordham Law Review, Vol. 91, 2022 Dmitry Karshtedt and Mark A. Lemley and Sean B. Seymore, The Death of the Genus Claim, 35 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 1 (Fall 2021) [SSRN] Daryl Lim, AI, Equality, and the IP Gap, Southern Methodist University Law Review (Forthcoming 2022) Daryl Lim, Antitrust’s AI Revolution, Tennessee Law Review (Forthcoming 2022) Daryl Lim, Confusion, Simplified, Berkeley Technology Law Journal (Forthcoming 2022) Daryl Lim, Trademark Confusion Revealed: An Empirical Analysis, American University Law Review (Forthcoming 2022) Adam Mossoff and Jonathan Barnett, Comment of Legal Academics, Economists, and Former Government Officials on Draft Policy Statement on the Licensing and Remedies for Standard Essential Patents (February 4, 2022) Sean M. O’Connor, “AI Replication of Musical Styles Points the Way to An Exclusive Rights Regime” (February 15, 2022). Research Handbook on Intellectual Property and Artificial Intelligence, Ryan Abbott ed. (Edward Elgar 2022 Forthcoming) Kristen Osenga, More Antitrust Scrutiny Of Pharma Won’t Help Patient Health (February 16, 2022), Law360 Eric A. Priest, The Future of Music Copyright Collectives in the Digital Streaming Age (December 23, 2021), Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts, Vol. 45, 2021 (published February 2022) Philip Stevens and Mark Schultz, The role of intellectual property rights inpreparing for future pandemics, Geneva Network (February 28, 2022) Raju Narayana Swamy, COVID-19 Pandemic: Should Nations Resort to Compulsory Licensing of Drugs and Vaccines? An Analysis of the Effect of Such Pervasive Steps and Non-Market Price-Setting on the Economics and Political Economy of Creative Industries (October 26, 2021) [SSRN, LexForti] Shine (Sean) Tu and Christopher M. Holman, Technology Changes Drive Legal Changes for Antibody Patents: What Patent Examiners Can Teach Courts About the Written Description and Enablement Requirements (February 3, 2022) [Note: Offer has been accepted to publish this article in the Berkeley Technology Law Journal]

This post comes from Sandra Aistars, Clinical Professor and Director of the Arts & Entertainment Advocacy Clinic at George Mason University, Antonin Scalia Law School, and Senior Fellow for Copyright Research and Policy & Senior Scholar at C-IP2.

On March 17, 2022, I had the pleasure to discuss Artificial Intelligence and Authorship with Dr. Ryan Abbott, the lawyer representing Dr. Stephen Thaler, inventor of the “Creativity Machine.” The Creativity Machine is the AI that generated the artwork A Recent Entrance to Paradise, which was denied copyright registration by the United States Copyright Office. Dr. Abbott, Dr. Thaler, and his AI have exhausted all mandatory administrative appeals to the Office and announced that they would soon sue the Office in order to obtain judicial review of the denial. You can listen to the conversation here.

Background:

Dr. Thaler filed an application for copyright registration of A Recent Entrance to Paradise (the Work) on November 3, 2018. For copyright purposes, the Work is categorized as a work of visual art, autonomously generated by the AI without any human direction or intervention. However, it stems from a larger project involving Dr. Thaler’s experiments to design neural networks simulating the creative activities of the human brain. A Recent Entrance to Paradise is one in a series of images generated and described in text by the Creativity Machine as part of a simulated near-death experience Dr. Thaler undertook in his overall research into and invention of artificial neural networks. Thaler’s work also raises parallel issues of patent law and policy which were beyond the scope of our discussion.

The registration application identified the author of the Work as the “Creativity Machine,” with Thaler listed as the claimant as a result of a transfer resulting from “ownership of the machine.” In his application, Thaler explained to the Office that the Work “was autonomously created by a computer algorithm running on a machine,” and he sought to “register this computer-generated work as a work-for-hire to the owner of the Creativity Machine.”[i]

The Copyright Office Registration Specialist reviewing the application refused to register the claim, finding that it “lacks the human authorship necessary to support a copyright claim.”[ii]

Thaler requested that the Office reconsider its initial refusal to register the Work, arguing that “the human authorship requirement is unconstitutional and unsupported by either statute or case law.”[iii]

The Office re-evaluated the claims and held its ground, concluding that the Work “lacked the required human authorship necessary to sustain a claim in copyright” because Thaler had “provided no evidence on sufficient creative input or intervention by a human author in the Work.”[iv]

37 CFR 202.5 establishes the Reconsideration Procedure for Refusals to Register by the Copyright Office. Pursuant to this procedure Thaler appealed the refusal to the Copyright Office Review Board comprised of The Register of Copyrights, The General Counsel of the Copyright Office and a third individual sitting by designation. The relevant CFR section requires that the applicant “include the reasons the applicant believes registration was improperly refused, including any legal arguments in support of those reasons and any supplementary information, and must address the reasons stated by the Registration Program for refusing registration upon first reconsideration. The Board will base its decision on the applicant’s written submissions.”

According to the Copyright Office, Thaler renewed arguments from his first two unsuccessful attempts before the Office that failure to register AI created works is unconstitutional, largely continued to advance policy arguments that registering copyrights in AI generated works would further the underlying goals of copyright law, including the constitutional rationale for protection, and failed to address the Office’s request to cite to case law supporting his assertions that the Office should depart from its reliance on existing jurisprudence requiring human authorship.

The Office largely dismissed Thaler’s second argument, that the work should be registered as a work made for hire as dependent on its resolution of the first—since the Creativity Machine was not a human being, it could not enter into a “work made for hire” agreement with Thaler. Here, the Office rejected the argument that, because corporations could be considered persons under the law, other non-humans such as AIs should likewise enjoy rights that humans do. The Office noted that corporations are composed of collections of human beings. The Office also explained that “work made for hire” doctrine speaks only to who the owner of a given work is.

Of course, both Dr. Abbott and the Copyright Office were bound in this administrative exercise by their respective roles: the Copyright Office must take the law as it finds it—although Dr. Abbott criticized the Office for applying caselaw from “the Gilded Age” as the Office noted in its rejection “[I]t is generally for Congress,” not the Board, “to decide how best to pursue the Copyright Clause’s objectives.” Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186, 212 (2003). The Board must apply the statute enacted by Congress; it cannot second-guess whether a different statutory scheme would better promote the progress of science and useful arts.”[v] Likewise, Dr. Abbott, acting on behalf of Dr. Thaler was required to exhaust all administrative avenues of appeal before pursuing judicial review of the correctness of the Office’s interpretation of constitutional and statutory directives, and case law.

Our lively discussion begins with level setting to ensure that the listeners understand the goals of Dr. Thaler’s project, goals which encompass scientific innovation, artistic creation, and apparently—legal and policy clarification of the IP space.

Dr. Abbott and I additionally investigate the constitutional rationales for copyright and how registering or not registering a copyright to an AI-created work is or is not in line with those goals. In particular, we debated utilitarian/incentive-based justifications, property rights theories, and how the rights of artists whose works might be used to train an AI might (or might not) be accounted for in different scenarios.

Turning to Dr. Thaler’s second argument, that the work should be registered to him as a work made for hire, we discussed the difficulties of maintaining the argument separately from the copyrightability question. It seems to me that the Copyright Office is correct that the argument must rise or fall with the resolution of the baseline question of whether a copyrightable work can be authored by an AI to begin with. The other challenging question that Dr. Abbott will face is how to overcome the statutory “work made for hire” doctrine requirements in the context of an AI-created work without corrupting what is intended to be a very narrow exception to the normal operation of copyright law and authorship. This is already a controversial area, and one thought by many to be unfavorable to individual authors because it deems a corporation to be the author of the work, sometimes in circumstances where the human author is not in a bargaining position to adequately understand the copyright implications or to bargain for them differently. In the case of an AI, the ability to bargain for rights or later challenge the rights granted, particularly if they are granted on the basis of property ownership, seems to be dubious.

In closing the discussion, Dr. Abbott confirmed that his client intends to seek judicial review of the refusal to register.

[i] Opinion Letter of Review Board Refusing Registration to Ryan Abbot (Feb. 14, 2022).

[ii] Id. (Citing Initial Letter Refusing Registration from U.S. Copyright Office to Ryan Abbott (Aug. 12, 2019).)

[iii] Id. (Citing Letter from Ryan Abbott to U.S. Copyright Office at 1 (Sept. 23, 2019) (“First Request”).)

[iv] Id. (Citing Refusal of First Request for Reconsideration from U.S. Copyright Office to Ryan Abbott at 1 (March 30, 2020).)

[v] Id at 4.

In Opposition to Copyright Protection for AI Works

This response to Dr. Ryan Abbott comes from David Newhoff.

On February 14, the U.S. Copyright Office confirmed its rejection of an application for a claim of copyright in a 2D artwork called “A Recent Entrance to Paradise.” The image, created by an AI designed by Dr. Stephen Thaler, was rejected by the Office on the longstanding doctrine which holds that in order for copyright to attach, a work must be the product of human authorship. Among the examples cited in the Copyright Office Compendium as ineligible for copyright protection is “a piece of driftwood shaped by the ocean,” a potentially instructive analog as the debate about copyright and AI gets louder in the near future.

What follows assumes that we are talking about autonomous AI machines producing creative works that no human envisions at the start of the process, other than perhaps the medium. So, the human programmers might know they are building a machine to produce music or visual works, but they do not engage in co-authorship with the AI to produce the expressive elements of the works themselves. Code and data go in, and something unpredictable comes out, much like nature forming the aesthetic piece of driftwood.

As a cultural question, I have argued many times that AI art is a contradiction in terms—not because an AI cannot produce something humans might enjoy, but because the purpose of art, at least in the human experience so far, would be obliterated in a world of machine-made works. It seems that what the AI would produce would be literally and metaphorically bloodless, and after some initial astonishment with the engineering, we may quickly become uninterested in most AI works that attempt to produce more than purely decorative accidents.

In this regard, I would argue that the question presented is not addressed by the “creative destruction” principle, which demands that we not stand in the way of machines doing things better than humans. “Better” is a meaningful concept if the job is microsurgery but meaningless in the creation or appreciation of art. Regardless, the copyrightability question does not need to delve too deeply into the nature or purpose of art because the human element in copyright is not just a paragraph about registration in the USCO Compendium but, in fact, runs throughout application of the law.

Doctrinal Oppositions to Copyright in AI Works

In the United States and elsewhere, copyright attaches automatically to the “mental conception” of a work the moment the conception is fixed in a tangible medium such that it can be perceived by an observer. So, even at this fundamental stage, separate from the Copyright Office approving an application, the AI is ineligible because it does not engage in “mental conception” by any reasonable definition of that term. We do not protect works made by animals, who possess consciousness that far exceeds anything that can be said to exist in the most sophisticated AI. (And if an AI attains true consciousness, we humans may have nothing to say about laws and policies on the other side of that event horizon.)

Next, the primary reason to register a claim of copyright with the USCO is to provide the author with the opportunity, if necessary, to file a claim of infringement in federal court. But to establish a basis for copying, a plaintiff must prove that the alleged infringer had access to the original work and that the secondary work is substantially or strikingly similar to the work allegedly copied. The inverse ratio rule applied by the courts holds that the more that access can be proven, the less similarity weighs in the consideration and vice-versa. But in all claims of copying, independent creation (i.e., the principle that two authors might independently create nearly identical works) nullifies any complaint. These are considerations not just about two works, but about human conduct.

If AIs do not interact with the world, listen to music, read books, etc. in the sense that humans do these things, then, presumably, all AI works are works of independent creation. If multiple AIs are fed the same corpus of works (whether in or out of copyright works) for the purpose of machine learning, and any two AIs produce two works that are substantially, or even strikingly, similar to one another, the assumption should still be independent creation. Not just independent, but literally mindless, unless again, the copyright question must first be answered by establishing AI consciousness.

In principle, AI Bob is not inspired by, or even aware of, the work of AI Betty. So, if AI Bob produces a work strikingly similar to a work made by AI Betty, any court would have to toss out BettyBot v. BobBot on a finding of independent creation. Alternatively, do we want human juries considering facts presented by human attorneys describing the alleged conduct of two machines?

If, on the other hand, an AI produces a work too similar to one of the in-copyright works fed into its database, this begs the question as to whether the AI designer has simply failed to achieve anything more than an elaborate Xerox machine. And hypothetical facts notwithstanding, it seems that there is little need to ask new copyright questions in such a circumstance.

The factual copying complication raises two issues. One is that if there cannot be a basis for litigation between two AI creators, then there is perhaps little or no reason to register the works with the Copyright Office. But more profoundly, in a world of mixed human and AI works, we could create a bizarre imbalance whereby a human could infringe the rights of a machine while the machine could potentially never infringe the rights of either humans or other machines. And this is because the arguments for copyright in AI works unavoidably dissociate copyright from the underlying meaning of authorship.

Authorship, Not Market Value, is the Foundation of Copyright

Proponents of copyright in AI works will argue that the creativity applied in programming (which is separately protected by copyright) is coextensive to the works produced by the AIs they have programmed. But this would be like saying that I have claim of co-authorship in a novel written by one of my children just because I taught them things when they were young. This does not negate the possibility of joint authorship between human and AI, but as stated above, the human must plausibly argue his own “mental conception” in the process as a foundation for his contribution.

Commercial interests vying for copyright in AI works will assert that the work-made-for-hire (WMFH) doctrine already implicates protection of machine-made works. When a human employee creates a protectable work in the course of his employment, the corporate entity, by operation of law, is automatically the author of that work. Thus, the argument will be made that if non-human entities called corporations may be legal authors of copyrightable works, then corporate entities may be the authors of works produced by the AIs they own. This analogizes copyrightable works to other salable property, like wines from a vineyard, but elides the fact that copyright attaches to certain products of labor, and not to others, because it is a fiction itself whose medium is the “personality of the author,” as Justice Holmes articulated in Bleistein.

The response to the WMFH argument should be that corporate-authored works are only protected because they are made by human employees who have agreed, under the terms of their employment, to provide authorship for the corporation. Authorship by the fictious entity does not exist without human authorship, and I maintain that it would be folly to remove the human creator entirely from the equation. We already struggle with corporate personhood in other areas of law, and we should ask ourselves why we believe that any social benefit would outweigh the risk of allowing copyright law to potentially exacerbate those tensions.

Alternatively, proponents of copyright for AI works may lobby for a sui generis revision to the Copyright Act with, perhaps, unique limitations for AI works. I will not speculate about the details of such a proposal, but it is hard to imagine one that would be worth the trouble, no matter how limited or narrow. If the purpose of copyright is to proscribe unlicensed copying (with certain limitations), we still run into the independent creation problem and the possible result that humans can infringe the rights of machines while machines cannot infringe the rights of humans. How does this produce a desirable outcome which does not expand the outsize role giant tech companies already play in society?

Moreover, copyright skeptics and critics, many with deep relationships with Big Tech, already advocate a rigidly utilitarian view of copyright law, which is then argued to propose new limits on exclusive rights and protections. The utilitarian view generally rejects the notion that copyright protects any natural rights of the author beyond the right to be “paid something” for the exploitation of her works, and this cynical, mercenary view of authors would likely gain traction if we were to establish a new framework for machine authorship.

Registration Workaround (i.e., lying)

In the meantime, as Stephen Carlisle predicts in his post on this matter, we may see a lot of lying by humans registering works that were autonomously created by their machines. This is plausible, but if the primary purpose of registration is to establish a foundation for defending copyrights in federal court, the prospect of a discovery process could militate against rampant falsification of copyright applications. Knowing misrepresentation on an application is grounds for invalidating the registration, subject to a fine of up to $2,500, and further implies perjury if asserted in court.

Of course, that’s only if the respondent can defend himself. A registration and threat of litigation can be enough to intimidate a party, especially if it is claimed by a big corporate tech company. So, instead of asking whether AI works should be protected, perhaps we should be asking exactly the opposite question: How do we protect human authorship against a technology experiment, which may have value in the world of data science, but which has nothing to do with the aim of copyright law?

About the IP Clause

And with that statement, I have just implicated a constitutional argument because the purpose of copyright law, as stated in Article I Clause 8, is to “promote science.” Moreover, the first three subjects of protection in 1790—maps, charts, and books—suggest a view at the founding period that copyright’s purpose, twinned with the foundation for patent law, was more pragmatic than artistic.

Of course, nobody could reasonably argue that the American framers imagined authors as anything other than human or that copyright law has not evolved to encompass a great deal of art which does not promote the endeavor we ordinarily call “science.” So, we may see AI copyright proponents take this semantic argument out for a spin, but I do not believe it should withstand scrutiny for very long.

Perhaps, the more compelling question presented by the IP clause, with respect to this conversation, is what it means to “promote progress.” Both our imaginations and our experiences reveal technological results that fail to promote progress for humans. And if progress for people is not the goal of all law and policy, then what is? Surely, against the present backdrop in which algorithms are seducing humans to engage in rampant, self-destructive behavior, it does seem like a mistake to call these machines artists.

The following post comes from Sabren H. Wahdan, a 3L at Scalia Law and a Research Assistant at C-IP2.

In one of his final majority opinions before announcing his retirement, Justice Steven Breyer penned a nuanced ruling that carefully threads the policy needle on copyright registration issues. The case pitted fabric designer Unicolors against fast fashion company H&M, but it was ultimately a victory for creators of art, fashion, music, dance, literary works, and others who rely on copyright registrations to protect their rights but lack the means to hire an attorney to ensure that their registration applications are legally and factually perfect. As a result of the ruling, they can register their works without fear that their registration could be invalidated by a good-faith mistake.

In one of his final majority opinions before announcing his retirement, Justice Steven Breyer penned a nuanced ruling that carefully threads the policy needle on copyright registration issues. The case pitted fabric designer Unicolors against fast fashion company H&M, but it was ultimately a victory for creators of art, fashion, music, dance, literary works, and others who rely on copyright registrations to protect their rights but lack the means to hire an attorney to ensure that their registration applications are legally and factually perfect. As a result of the ruling, they can register their works without fear that their registration could be invalidated by a good-faith mistake.

Unicolors v. H&M answers a narrow question of copyright law: what is the requisite level of knowledge to invalidate copyright registration? Justice Stephen Breyer’s majority (6-3) opinion holds that actual knowledge of either a factual or legal mistake is required before a registration is invalidated. This makes good sense because copyright registration applications are often completed by creators who are not lawyers. Some background on the case is useful.

The District Court

In 2016, Unicolors sued H&M for copyright infringement in the United States District Court for the District of Central California, alleging that H&M sold apparel, specifically a jacket and skirt, with a design remarkably similar to a Unicolors-copyrighted design. The jury returned a verdict in favor of Unicolors.[i] Subsequently, H&M filed a renewed motion for judgment as a matter of law, arguing that Unicolors’ copyright registration was invalid because Unicolors knowingly submitted inaccurate information in its application for registration.[ii] The U.S. Copyright Office has established an administrative procedure that allows an applicant to register multiple works that were physically packaged or bundled together as a single unit and first published on the same date.[iii] However, under 37 C.F.R. § 202.3(b)(4), an applicant cannot use this provision if the works were published in different units or first distributed as separate, individual works.

Unicolors had filed an application with the Copyright Office seeking a collective copyright registration for thirty-one of its designs in 2011. H&M contended that Unicolors could not do so because it had sold some of the patterns separately to different customers at different times, invalidating Unicolors’ registration.[iv] The District Court denied H&M’s motion for judgment as a matter of law, holding that a registration may be valid even if it contains inaccurate information, provided the registrant did not know the information was inaccurate.[v] H&M had to show Unicolors had knowledge and intent to defraud in order to invalidate the registration. H&M appealed.[vi]

The Ninth Circuit Decision

On appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed the District Court’s judgment holding that invalidation under 17 U.S. Code § 411 does not require a showing that the registration applicant intended to defraud the Copyright Office.[vii] In other words, knowing about the inclusion of inaccurate facts and law in an application is enough to warrant invalidation. Furthermore, the Ninth Circuit stated that Unicolors had failed to satisfy 37 C.F.R. § 202.3(b)(4) – the single unit of publication requirement.[viii] The Court found that Unicolors’ registration was inaccurate because Unicolors registered all thirty-one of its designs together as a single unit with the same publication date, when in fact, the designs were not all published as a single unit. Some designs were available to the public, while others were confined designs only available to particular exclusive customers.[ix] The Court determined that Unicolors knew the designs would not be released together at the same time; therefore, they knew that the registration information was inaccurate.[x] Consequently, the Ninth Circuit remanded the case to the District Court for further proceedings.[xi]

The Supreme Court Reverses the Ninth Circuit Decision

In 2021, Unicolors filed a petition to the Supreme Court asking whether the Ninth Circuit erred in determining that §411(b)(1)(A) required referral to the Copyright Office on any inaccurate registration information, even without evidence of fraud or material error in conflict with other circuit courts and the Copyright Office’s own findings on §411(b)(1)(A). The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Justice Breyer’s Majority Opinion

Justice Breyer is well known for his use of analogies to probe the arguments of parties appearing before the Court. Likewise, in Unicolors, the majority opinion relied not only on statutory construction, legislative history, and the plain language of the statute as informed by dictionary definitions, but also on analogies––both to adjacent provisions of the code, and to analogies involving birdwatching––to reach its conclusion, in the end finding that §411(b)(1)(A) does not distinguish between a mistake of law and a mistake of fact and thus excuses inaccuracies in registration applications premised on either mistakes of fact or law.

To explain employing Justice Breyer’s birdwatching analogy, Breyer imagines a man who sees a flash of red in a tree and mistakenly says it is a cardinal when the bird is actually a scarlet tanager: “[A man] may have failed to see the bird’s black wings. In that case, he has made a mistake about the facts.” Alternatively, if said man saw “the bird perfectly well, noting all of its relevant features,” it is possible that, “not being much of a birdwatcher, he may not have known that a tanager (unlike a cardinal) has black wings.” For Breyer, that is a “labeling mistake” because the man “saw the bird correctly, but does not know how to label what he saw” (analogous to a mistake of law).[xii] A business person in the arts may know specific facts about her business; however, she may not be cognizant of how the law applies to it and applies the law to those facts inaccurately. §411(b)(1)(A) states that a certificate of registration satisfies the requirements of section 411 and section 412, regardless of whether the certificate contains any inaccurate information–—unless the inaccurate information was included on the application for copyright registration with knowledge that it was inaccurate.

The plain language of the text does not support an interpretation that would read constructive knowledge of how legal requirements bear on the facts at issue into the standard. To reach this conclusion, the majority opinion analyzed not only the plain language of the text but also “case law and the dictionary to find that “knowledge” means an applicant’s understanding of the relevant law that applies to the submitted information.[xiii] Therefore, an applicant who believes information submitted on a registration application is accurate cannot have acted with knowledge that the information was inaccurate.

The Majority also examined other provisions in the Copyright Act that refer specifically to circumstances where an individual should have been aware that a particular legal requirement is implicated (e.g., “‘reasonable grounds to know . . .,’” “‘reasonable grounds to believe . . .,`” ”‘not aware of facts or circumstances from which . . . is apparent’” and concluded that §411(b)(1)(A) does not contain any such analogous language.[xiv]

According to the majority, “the absence of similar language in the statutory provision before us tends to confirm our conclusion that Congress intended ‘knowledge’ here to bear its ordinary meaning.” When Congress includes particular language in one section of a statute but omits it in another, there is a presumption that Congress intended a difference in meaning.[xv]

Finally, the majority considered the legislative history of the Copyright Act. The Court understood that Congress wanted to make it easier, not more difficult, for artists and nonlawyers to obtain valid copyright registrations. Congress did not intend for good-faith errors to invalidate registrations, whether those errors were in issues of fact or issues of law. Invalidating copyright registration when a copyright owner was unaware of or misunderstood the law undermines the purpose of the Copyright Act. The Court dismissed the often-cited legal maxim that ignorance of the law is not an excuse by stating that it does not apply to civil cases concerning the scope of a statutory safe harbor that arises from ignorance of collateral legal requirement.[xvi]

Justice Thomas’ Dissent

Careful readers will note that the question the majority opinion answers is somewhat different from that granted certiorari. Justice Clarence Thomas filed a dissenting opinion, joined by Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch, arguing primarily that the majority decided a question not properly presented to the Court. The question originally taken up by the Court was whether fraud was necessary to invalidate a registration. The majority found that the knowledge question is close enough to the question presented in the petition to qualify as a “subsidiary question fairly included” in the question presented.[xvii]

Justice Thomas, not joined by Justice Gorsuch, further dissents from the majority view that ignorance of the law is not an excuse.[xviii] He would have ruled that individuals are responsible for knowing the law, whether that be in the context of criminal or civil cases.

Conclusion

Based on the ruling, a mistake in an application for copyright registration is excusable so long as the copyright registrant or claimant lacked actual knowledge of the inaccuracy. The more complex issue perhaps is the proof issue––proving the relevant knowledge or lack of knowledge. While some may worry that there is a risk that claimants will falsely argue lack of knowledge, courts are well-versed in evaluating truthfulness and parsing evidence, including when they must evaluate subjective viewpoints and experiences.

The majority opinion demonstrates a sensitive balancing of the interest in promoting accurate registration with the understanding of the challenges faced by artists, creators, and other non-lawyers who may unintentionally make errors in filing registrations. Importantly, this decision gives little shelter to copyright lawyers if they register works and make a mistake; on the contrary, it should serve as a warning to copyright lawyers to be careful when filing a copyright registration lest they face potential validity challenges in the future.

The case is going back down to the Ninth Circuit on remand, and the question is: what facts and law did Unicolors know when it filed these registration applications?

[i] Unicolors, Inc. v. H&M Hennes & Mauritz, L.P., 959 F.3d 1194, at 1195* (2020).

[ii] Id at 1197.

[iii] See U.S. Copyright Office, Circular No. 34: Multiple Works (2021).

[iv] Unicolors, 959 F.3d 1194, at 1195 (2020).

[v] Id at 1197.

[vi] Id.

[vii] Id at 1200.

[viii] Id.

[ix] Id at 1197.

[x] Id.

[xi] Id.

[xii] Unicolors Inc. v. H&M Hennes & Mauritz L.P., No. 20-915, 2022 WL 547681, at 4* (2022).

[xiii] Unicolors, WL 547681, at 4*(2022) (citing Intel Corp. Investment Policy Comm. v. Sulyma, 589 U. S. 140 S.Ct. 768, 776, 206 L.Ed.2d 103 (2020)).

[xiv] Unicolors, WL 547681, at 5*(citing §121A(a), §512(c)(1)(A), §901(a)(8), §1202(b) and §1401(c)(6)).

[xv] Unicolors, WL 547681, at 5* (2022) (citing Nken v. Holder, 556 U. S. 418, 430 (2009)).

[xvi] Unicolors, WL 547681, at 8*(2022) (citing Rehaif v. United States, 588 U. S. (2019)).

[xvii] Unicolors, WL 547681, at 8*(2022).

[xviii] Id.

By Molly Stech*

*The blog post below and the law review article it links to are the individual thoughts and views of the author and should not be attributed to any entity with which she is currently or has been affiliated.

In a forthcoming article in the Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law, I review the law and jurisprudence concerning joint authorship and provide an analysis of it with specific emphasis on photographers and portrait subjects. I wrote and edited this paper in conjunction with the George Mason University Scalia School of Law’s 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship, and am very grateful for the thoughtful comments I received from Senior Commentators and scholars involved with the Fellowship.

In a forthcoming article in the Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law, I review the law and jurisprudence concerning joint authorship and provide an analysis of it with specific emphasis on photographers and portrait subjects. I wrote and edited this paper in conjunction with the George Mason University Scalia School of Law’s 2021-2022 Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship, and am very grateful for the thoughtful comments I received from Senior Commentators and scholars involved with the Fellowship.

A recent string of litigation in this space, and the general question of ownership interests in one’s own likeness, are what prompted my interest. Paparazzi have filed lawsuits against models and other celebrities for reposting images of themselves on their social media feeds, without permission from or compensation for the photographer. Some celebrities have countersued, but many of these cases settle out of court. In a best-case scenario, paparazzi and their subjects enjoy a mutually-beneficial relationship, but these lawsuits highlight a problematic legal space. It is accepted domestically and abroad that copyright subsists in the vast majority of photographs and that the copyright belongs to the photographer. The bar to copyrightability is notoriously low; it requires only a modicum of creativity.

Photographers have a wide range of creative choices they can highlight to showcase where their authorship lies in a given photograph, including the camera and film used, the angle, the lighting, and the backdrop. What I explore in this paper is the possibility that subjects of photographs may also contribute copyrightable authorship to a given photograph, and may therefore be eligible to be deemed co-authors of certain photographs with the photographer. Copyright law aims to reward creative expression. Nothing in the statute can be read to proactively deny a subject co-authorship. I point out that copyright law is accustomed to doing the hard work of factual analysis (see, e.g., the fair use doctrine) and that any given work, including a photograph, should be considered on its own for purposes of correctly identifying authorial contribution. In some cases, a subject will contribute copyrightable expression by posing her limbs, arranging her facial expression, selecting her garments, or even arranging how her garments fall. So long as the contribution is adequately creative, co-authorship should be hers.

Joint (or Contributing) Authorship: Roadblocks

Two barriers to overcome in reaching this conclusion include some courts’ emphasis on joint authors’ intent; and some courts’ prerequisite that every contribution to a jointly-authored work be independently copyrightable. I address each of these problems in turn and underline that the statute itself does not make these requirements. Admittedly, in U.S. law, these are not easily surmountable obstacles. But, in taking copyright law back to its first principles, I believe the correct answer can be found in reemphasizing creative contribution. A recent case in the United Kingdom demonstrates an admirable flexibility that tailors an assignment of authorship to the degree of authorial contribution. An apportionment of authorship can be discerned from analyzing works one at a time. As mentioned, U.S. copyright law is no stranger to a work-by-work analysis in its fair use doctrine; another example is the idea-expression dichotomy, which provides that the more a work merges with its inevitable expression, the thinner its depth of copyright protection.

Other Thinking on These Issues

Any timely issue is likely to invite the contributions of other scholars, and this topic is no different. Other scholars have suggested sui generis rights for paparazzi subjects; separate types of exclusive rights for social media; and a personality-based right that could stretch copyright-like rights from covering “works” to people themselves. Another scholar argued persuasively for paparazzi subjects to receive an implied license to use photographs of themselves in certain ways. My analysis remains proscribed within copyright law itself, with the baseline argument that authorial creativity, whatever its guise, should be rewarded with rights.

There are other interesting avenues that are being explored to solve a similar problem, and I will follow them with interest. The right of privacy, a fascinating and complex legal discipline, may also offer solutions in the future. My paper mostly sidesteps the phenomenon of revenge porn, for example, and while a copyright argument could be made in the average scenario (no matter who pushes “record,” there are two people potentially offering creative expression to the final film), privacy law may be a more logical solution to protecting those subjects than copyright law. Another related argument that works in my favor, I believe, is rooted in freedom of expression. If copyright law is the engine of free expression, so should it contribute to people having a legal stake in their photographic likeness in order to control or at least contribute to the narrative attached to that photograph.

The paper is available in draft form at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4049946

And it will be available in late 2022 from Vanderbilt’s JETLaw website: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/

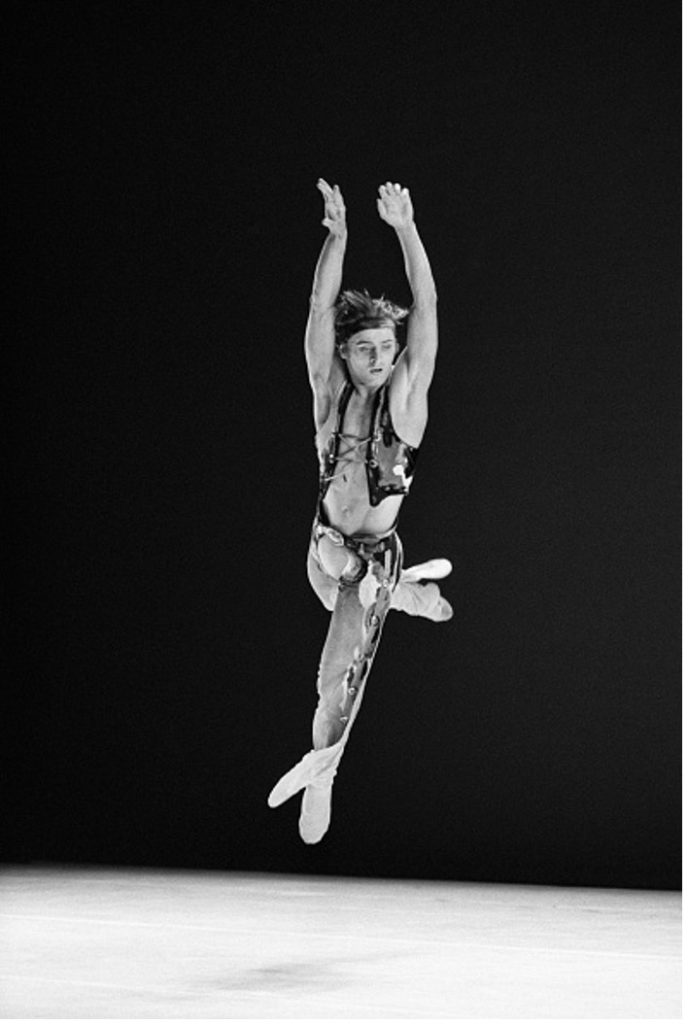

Santa Fe Saga, April 14, 1978. © Getty Images

Examples

While a revenge porn video may not make the best example for my analysis, I believe that selfies and photographs of dancers onstage do help demonstrate my view. A selfie is probably a copyrightable work. But in analyzing a given selfie to ascertain where the creativity lies, it will likely be in the pose, the facial expression, and the garments (the subject’s choices) as much as it will be in the framing, the backdrop, and the angle (the photographer’s choices). The photographer and the subject are of course the same person in the case of the selfie, but in deconstructing a photograph and searching for its authorial qualities, an argument certainly exists for the former forms of authorship as much as for the latter. And for a dancer onstage, his or her pose, facial expression, turnout, limb extension, jump arc, makeup, and any number of other attributes cannot reasonably be the result of the photographer’s efforts or talent, although the resulting photograph will of course likely benefit from them.

Conclusion

Co-authorship may exist in certain photographic portraits. It is essential that copyright law reexamine its interpretation of joint authorship in order to better capture and reward the contributions of the parties who offer creative expression to any given copyrightable work.

Greetings from C-IP2 Faculty Director Sean O’Connor

Greetings from C-IP2 Faculty Director Sean O’Connor

Warmest greetings for this holiday season. While 2021 has continued to be challenging, we are thankful that our community has stayed strong and thrived, nonetheless. We hope that if the pandemic has directly affected you or your loved ones, you are finding your way back to peace and health. As difficult as these times can be for many of us, I think we all know that it has been even harder for others. Take extra time this holiday season to be with loved ones and reflect on the things we do have.

In this Winter 2021 Progress Report, we include not only our news the last quarter of 2021, but also a recap of major developments this year.

This year we accomplished several major goals that have been in the works for a few years.

-

- Rebranded the Center. While our old name had developed good brand recognition, it had outlived much of its original usefulness and did not fully reflect the range of work we do in the innovation ecosystem. It is also important to signal that intellectual property (IP) is a core part of such ecosystems.

- Formed Advisory Board. A strong center such as ours needs the guidance of leaders in IP and innovation. We are so thankful that our “dream team” of influential leaders accepted our invitation to advise us. The Board includes:

- Troy Dow, Vice President and Counsel, Government Relations and IP Legal Policy and Strategy, The Walt Disney Company

- Mitch Glazier, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Recording Industry Association of America

- Dr. Kirti Gupta, Vice President, Economic Strategy | Chief Economist, Qualcomm

- Lawrence Horn, President and Chief Executive Officer, MPEG LA, LLC

- Andrei Iancu, Partner, Irell Manella LLP, Los Angeles, California; Former Director, United States Patent & Trademark Office

- David J. Kappos, Partner, Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP, New York; Former Director, United States Patent & Trademark Office

- John Kolakowski, Director, Patent Licensing, & Head of IP Regulatory Affairs, North America, Nokia Technologies