Led by Prof. Adam Mossoff and C-IP2 Senior Fellow and Senior Scholar Prof. Jonathan M. Barnett, twenty-five law professors, economists, and former United States Government officials—including C-IP2 Advisory Board members the Honorable Andrei Iancu, the Honorable David J. Kappos, the Honorable Paul Michel, and the Honorable Randall R. Rader; Faculty Director Prof. Sean M. O’Connor; Senior Scholar Prof. Kristen Osenga; and Scholar Dr. Bowman Heiden—submitted a letter in response to a “call for evidence” on the licensing, litigation, and remedies of standard-essential patents (SEPs). The response discusses core functions of SEPs in the wireless ecosystem, the lack of evidence of Patent Holdup and Royalty Stacking, assumptions about SEPs and Market Power, the importance of the potential for injunctive relief even for FRAND, levels of licensing, and SEP licensing in SME markets. The letter is available here on SSRN.

Tag: Adam Mossoff

The U.S. Copyright Office released its long-awaited report on Section 512 of Title 17 late last week. The Report is the culmination of more than four years of study by the Office of the safe harbor provisions for online service provider (OSP) liability in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA). Fortuitously, the study period coincided with the launch of Scalia Law’s Arts and Entertainment Advocacy Clinic. Clinic students were able to participate in all phases of the study, including filing comments on behalf of artists and CPIP scholars, testifying at roundtable proceedings on both coasts, and conducting a study of how OSPs respond to takedown notices filed on behalf of different types of artists. The Office cites the filings and comments of Scalia Law students numerous times and ultimately adopts the legal interpretation of the law advocated by the CPIP scholars.

The U.S. Copyright Office released its long-awaited report on Section 512 of Title 17 late last week. The Report is the culmination of more than four years of study by the Office of the safe harbor provisions for online service provider (OSP) liability in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA). Fortuitously, the study period coincided with the launch of Scalia Law’s Arts and Entertainment Advocacy Clinic. Clinic students were able to participate in all phases of the study, including filing comments on behalf of artists and CPIP scholars, testifying at roundtable proceedings on both coasts, and conducting a study of how OSPs respond to takedown notices filed on behalf of different types of artists. The Office cites the filings and comments of Scalia Law students numerous times and ultimately adopts the legal interpretation of the law advocated by the CPIP scholars.

The Office began the study in December 2015 by publishing a notice of inquiry in the Federal Register seeking public input on the impact and effectiveness of the safe harbor provisions in Section 512. Citing testimony by CPIP’s Sean O’Connor to the House Judiciary Committee that the notice-and-takedown system is unsustainable given the millions of takedown notices sent each month, the Office launched a multi-pronged inquiry to determine whether Section 512 was operating as intended by Congress.

Scalia Law’s Arts and Entertainment Advocacy Clinic drafted two sets of comments in response to this initial inquiry. Terrica Carrington and Rebecca Cusey submitted comments to the Office on behalf of middle class artists and advocates, including Blake Morgan, Yunghi Kim, Ellen Seidler, David Newhoff, and William Buckley, arguing that the notice-and-takedown regime under Section 512 is “ineffective, inefficient, and unfairly burdensome on artists.” The students pointed out that middle class artists encounter intimidation and personal danger when reporting infringements to OSPs. Artists filing takedown notices must include personal information, such as their name, address, and telephone number, which is provided to the alleged infringer or otherwise made public. Artists often experience harassment and retaliation for sending notices. The artists, by contrast, obtain no information about the identity of the alleged infringer from the OSP. The Office’s Report cited these problems as a detriment for middle class artists and “a major motivator” of its study.

A second response to the notice of inquiry was filed by a group of CPIP scholars, including Sandra Aistars, Matthew Barblan, Devlin Hartline, Kevin Madigan, Adam Mossoff, Sean O’Connor, Eric Priest, and Mark Schultz. These comments focused solely on the issue of how judicial interpretations of the “actual” and “red flag” knowledge standards affect Section 512. The scholars urged that the courts have interpreted the red flag knowledge standard incorrectly, thus disrupting the incentives that Congress intended for copyright owners and OSPs to detect and deal with online infringement. Several courts have interpreted red flag knowledge to require specific knowledge of particular infringing activity; however, the scholars argued that Congress intended for obvious indicia of general infringing activity to suffice.

The Office closely analyzed and ultimately adopted the scholars’ red flag knowledge argument in the Report:

The Office went on to state that “a standard that requires an OSP to have knowledge of a specific infringement in order to be charged with red flag knowledge has created outcomes that Congress likely did not anticipate.” And since “courts have set too high a bar for red flag knowledge,” the Office concluded, Congress’ intent for OSPs to act upon information of infringement has been subverted. This echoed the scholars’ conclusion that the courts have disrupted the balance of responsibilities that Congress sought to create with Section 512 by narrowly interpreting the red flag knowledge standard.

Scalia Law students and CPIP scholars likewise participated in roundtable hearings on each coast to provide further input for the Copyright Office’s study of Section 512. The first roundtable was held on May 2-3, 2016, in New York, New York, at the Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse, where the Second Circuit and Southern District of New York hear cases. The roundtable was attended by CPIP’s Sandra Aistars and Matthew Barblan. They discussed the notice-and-takedown process, the scope and impact of the safe harbors, and the future of Section 512. The second roundtable was held in San Francisco, California, at the James R. Browning Courthouse, where the Ninth Circuit hears cases. Scalia Law student Rebecca Cusey joined CPIP’s Sean O’Connor and Devlin Hartline to discuss the notice-and-takedown process, applicable legal standards, the scope and impact of the safe harbors, voluntary measures and industry agreements, and the future of Section 512. Several of the comments made by the CPIP scholars at the roundtables ended up in the Office’s Report.

In November 2016, the Office published another notice of inquiry in the Federal Register seeking additional comments on the impact and effectiveness of Section 512. The notice itself included citations to the comments submitted by Scalia Law students and the comments of the CPIP scholars. Under the guidance of Prof. Aistars, the students from Scalia Law’s Arts and Entertainment Advocacy Clinic again filed comments with the Office. Clinic students Rebecca Cusey, Stephanie Semler, Patricia Udhnani, Rebecca Eubank, Tyler Del Rosario, Mandi Hart, and Alexander Summerton all contributed to the comments, which discussed their work in helping individuals and small businesses enforce their copyright claims by submitting takedown notices pursuant to Section 512. The students reported on the practical barriers to the effective use of the notice-and-takedown process at particular OSPs. Two problems identified by the students were cited by the Copyright Office as examples of how OSPs make it unnecessarily difficult to submit a takedown notice. Accordingly, the Office called on Congress to update the relevant provisions of Section 512.

Two years after the additional written comments were submitted, the Office announced a third and final roundtable to be held on April 8, 2019, at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. The purpose of this meeting was to discuss any relevant domestic or international developments that had occurred during the two prior years. CPIP’s Devlin Hartline attended this third roundtable to discuss recent case law related to Section 512, thus ensuring that CPIP scholars were represented at all three of the Office’s roundtables.

CPIP congratulates and thanks the students of Scalia Law’s Arts and Entertainment Advocacy Clinic for their skillful advocacy on behalf of artists who otherwise would not be heard in these debates.

Earlier this week, a coalition of over 125 publishers and non-profit scientific societies joined the Association of American Publishers (AAP) in a letter to the White House expressing serious concerns with a proposed Administration policy that would override intellectual property rights and threaten the advancement of scientific scholarship and innovation. In a flawed attempt to advance open access goals, the policy would require the free and immediate distribution of any proprietary articles that report on research funded by a government agency. But overwhelming opposition by dozens of the most esteemed medical societies and research organizations reveals an ill-conceived and hasty proposal that would not only disregard long-established intellectual property rights, but would also adversely affect U.S. jobs, research, innovation, and global competitiveness.

Earlier this week, a coalition of over 125 publishers and non-profit scientific societies joined the Association of American Publishers (AAP) in a letter to the White House expressing serious concerns with a proposed Administration policy that would override intellectual property rights and threaten the advancement of scientific scholarship and innovation. In a flawed attempt to advance open access goals, the policy would require the free and immediate distribution of any proprietary articles that report on research funded by a government agency. But overwhelming opposition by dozens of the most esteemed medical societies and research organizations reveals an ill-conceived and hasty proposal that would not only disregard long-established intellectual property rights, but would also adversely affect U.S. jobs, research, innovation, and global competitiveness.

Like other open access mandate proposals in the past, there has been no evidence offered that the untested models are viable or sustainable or that there are systematic failures in the current scholarly publishing market. In a policy brief published in 2017, CPIP identified similar proposals as nothing but solutions in search of a problem—clear examples of regulatory overreach lacking any empirical evidence of why they are needed and how they would be beneficial.

Proposed Policy Eliminates Any Opportunity to Commercialize

Proprietary articles that report on federally funded research—such as those published in leading medical and scientific journals—are currently subject to public access mandates that require them to be made publicly available no later than 12 months after publication. These mandates are meant to balance the interests of the public in accessing these works with those of publishers and non-profit organizations that bear the costs of producing them. It’s a framework that, while not perfect, reflects the Constitutional objective of securing exclusive rights to promote the progress of science and the useful arts.

Notwithstanding this long-understood trade-off between access and exclusivity, the proposed policy would require the immediate and free distribution of journal articles reporting on any amount of federally funded research. If implemented, the proposal would deny publishers any opportunity to recoup the investments made in development of these labor and cost-intensive works, and many journals and research organizations would simply no longer be able to operate. While the proposal may be rooted in a desire to benefit the public, its complete eradication of the already short 12-month embargo reveals a troubling unawareness of existing markets, the critical role of publishers, and the value of intellectual property.

Untested Model Reflects Unawareness of Creative Ecosystems

Unfortunately, proposals like this reflect a belief by some that in the digital age publishers are merely intermediaries who restrict access to works. Those who promote this narrative also tend to favor short-term access and distribution over sustainable industries, long term R&D, and free markets, but their efforts to impose sweeping open access provisions reveal an ignorance of the inner workings and contributions of the publishing industry.

The reality is that even when federal funding exists for underlying research, significant investments are required by non-profit journals and publishers to translate the research into high-quality articles. These organizations must dedicate time and resources to the review and selection of articles, management of the peer review process, editing, curating, distributing, and long-term stewardship.[i] The publishing industry employs thousands of Americans to carry out these tasks, and they fund their efforts at no cost to taxpayers. Additionally, the sale of journal subscription in hundreds of foreign countries contributes significantly to the U.S. economy and trade balance.

Perhaps most disturbing is that those promoting the proposal seem unaware or unconcerned with the potential devastating impact the policy would have on publishing and scientific communities and America’s leadership in research and innovation. Stakeholders representing the industries that stand to be most affected by an unfettered and unproven open access policy have been left out of discussions, resulting in an ill-considered and inequitable proposal. Furthermore, the fact that the details of Administration policies are sometimes not disclosed until they are announced and implemented raises serious questions about the development of a policy that could have such a significant impact on industries, jobs, and the U.S. economy.

Strong Opposition to an Unsound Policy

Taking into account these numerous problems, it’s not surprising that stakeholders have now joined together to voice their opposition to the proposed policy. Venerable institutions such as the American Medical Association, the American Cancer Society, and the New England Journal of Medicine are just a few of the dozens of scientific, medical, and publishing organizations to challenge the proposal. In addition to these stakeholder organizations, Senator and Chairman of the Subcommittee on Intellectual Property Thom Tillis recently voiced his concerns with the proposal in a letter to Secretary of the Department of Commerce, Wilbur Ross, and to White House Chief of Staff, Mick Mulvaney. He writes:

If the current policy is changed—particularly without benefit of public hearings and stakeholder input—it could amount to significant government interference in an otherwise well-functioning private marketplace that gives doctors, scientific researchers and others options about how they want to publish these important contributions to science.

As Senator Tillis and others point out, the proposed policy has been put forward with no input from stakeholders or public comment. No evidence has been presented that a revised policy is needed, nor has the existing marketplace been shown to be dysfunctional.

While the wide distribution of and access to scholarly articles is critical to advancing research and education, it shouldn’t be so overvalued as to disregard all that goes into producing them and the associated intellectual property rights. To do so would represent a short-term fix to a problem that has not been proven to exist and result in untold damage to publishing industries, the economy, and ultimately the public.

[i] For a detailed account of the value-add services provided scholarly publishers, see Professor Adam Mossoff’s article How Copyright Drives Innovation: A Case Study of Scholarly Publishing in the Digital World.

On December 21, 2018, CPIP Senior Scholars Adam Mossoff and Kristen Osenga joined former Federal Circuit Chief Judge Randall Rader and SIU Law’s Mark Schultz in comments submitted to the FTC as part of its ongoing Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century Hearings. Through the hearings, the FTC is examining whether recent economic or technological changes warrant adjustments to competition or consumer protection laws. The comments submitted to the FTC explain how the FTC itself is harming innovation in the health sciences by meddling in patent disputes between branded and generic drug companies.

On December 21, 2018, CPIP Senior Scholars Adam Mossoff and Kristen Osenga joined former Federal Circuit Chief Judge Randall Rader and SIU Law’s Mark Schultz in comments submitted to the FTC as part of its ongoing Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century Hearings. Through the hearings, the FTC is examining whether recent economic or technological changes warrant adjustments to competition or consumer protection laws. The comments submitted to the FTC explain how the FTC itself is harming innovation in the health sciences by meddling in patent disputes between branded and generic drug companies.

The introduction is copied below, and the comments can be downloaded here.

***

How Antitrust Overreach is Threatening Healthcare Innovation

Imagine passing a rigorous test with flying colors, only to be told that you need to start over because you weren’t wearing the right clothing or you wrote your answers in the wrong color. Does that sound silly? Unfair? That scenario is happening to the American pharmaceutical industry thanks to regulators at the Federal Trade Commission who aren’t content to let the Food & Drug Administration (the experts in pharmaceutical safety and regulation) and federal courts (which referee disputes between branded and generic drug companies) decide when new drugs are ready to come to market. The consequences of these regulatory actions impact people’s lives.

The development and widespread availability of safe and effective pharmaceutical products has helped people live longer and better lives. The pharmaceutical industry invests billions each year in research and infrastructure and employs millions of Americans. The industry is closely regulated by many agencies, most notably the FDA, which requires extensive testing for safety and effectiveness before new drugs enter the market. Many thoughtful proposals have been advanced to improve and modernize the FDA’s review and approval of new drugs, but there is broad agreement that the FDA’s basic role in drug approval serves valid ends.

In recent years, however, other government agencies have played an increasingly intrusive role in deciding whether and when new drugs can enter the market. One such agency is the Federal Trade Commission, which has recently taken steps to block branded drug companies from settling patent litigation with generic drug makers. The FTC substitutes its own judgment for the business judgment of sophisticated parties, simultaneously weakening the patent rights of branded drug companies that spend billions in drug discovery and development and delaying generic drug companies from bringing consumers low cost alternatives to branded drugs. This example of government agencies picking winners and losers—indeed, deciding there should be no winners and losers—harms consumers in the short run by slowing access to drugs and in the long run by weakening innovation.

This paper describes the role of patents in protecting drugs and the special patent litigation regime Congress enacted in the 1980s to carefully balance the needs of branded drug companies, generic competitors, and consumers. Although these systems are not perfect, the FTC’s overreach in its regulatory powers in this area of the innovation economy results in a net loss for American consumers, as described below.

To read the comments, please click here.

On December 21, 2018, CPIP Senior Scholars Jonathan Barnett, Chris Holman, Erika Lietzan, Adam Mossoff, Sean O’Connor, and Kristen Osenga joined a comment letter that was filed with the FTC as part of its ongoing hearings on Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century. The comment letter was joined by 18 legal academics, economists, and former government officials—including former USPTO Director David Kappos and former Federal Circuit Chief Judge Paul Michel. The comment letter is copied below.

On December 21, 2018, CPIP Senior Scholars Jonathan Barnett, Chris Holman, Erika Lietzan, Adam Mossoff, Sean O’Connor, and Kristen Osenga joined a comment letter that was filed with the FTC as part of its ongoing hearings on Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century. The comment letter was joined by 18 legal academics, economists, and former government officials—including former USPTO Director David Kappos and former Federal Circuit Chief Judge Paul Michel. The comment letter is copied below.

***

December 21, 2018

Via Electronic Submission

Mr. Donald S. Clark

Secretary of the Commission

Federal Trade Commission

600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20580

Re: Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century Hearings—

Public Comments Following Hearing #4 on Innovation and Intellectual Property Policy

Dear Secretary Clark,

As legal academics, economists, and former government officials who are experts in antitrust law and intellectual property law, we respectfully submit these comments and an Appendix in response to the request for public comments following the Federal Trade Commission’s Hearings on Innovation and Intellectual Property Policy held October 23-24, 2018, as part of the FTC’s Hearings on Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century.

We support evidence-based policy-making by the FTC concerning all aspects of technological innovation, intellectual property (IP) rights, and the relationship between IP rights and innovation markets. It is imperative that the FTC ground any policy statements, investigations, or enforcement actions, not on academic theories about how IP rights might potentially be misused in stylized theoretical models, but on persuasive evidence of actual consumer harm from anti-competitive practices in real-world markets. Otherwise, regulatory overreach could undermine the economic incentives and resulting stream of innovative products and services that consumers enjoy in markets in which reliable and effective IP rights attract the private capital necessary to fund the high costs of R&D and the commercialization process.

Few economists and policymakers would question that reliable and effective property rights are a necessary predicate for supporting investment in conventional physical-goods markets. Logic holds that this economic principle applies for the innovators, investors, and entrepreneurs in the information technology and life sciences markets at the core of the US innovation economy.

Given reliable and effective IP rights, multiple empirical studies support the proposition that firms are more willing to incur substantial costs and bear significant risks in undertaking long-term R&D. Two well-known examples are the approximately $2.6 billion dollars required to bring a new drug to market or the billions in dollars required to develop new communications technologies like 5G. These and other long-term R&D investments occur in commercial environments in which courts and administrative agencies secure reliable and effective IP rights.

In recent years, antitrust agencies have sometimes taken policy actions in IP-intensive markets that overlook this fundamental connection between secure property rights, investment incentives, R&D, and commercialization activities. These regulatory actions have been based on academic theories and anecdotal reports that have not been put to thoroughgoing, rigorous empirical tests.

To illustrate the risks of making policy without firm empirical support, consider the smartphone industry. For over a decade, theoretical predictions have been made that comparatively high numbers of patents covering technologies used in a single multi-component consumer product—a smartphone—would create “patent thickets,” “royalty stacking,” and “patent holdup” that would increase prices, constrain output, and stunt innovation. Based on these conjectures, antitrust agencies around the world have issued policy statements, undertaken enforcement actions, and imposed billions of dollars in fines—often directed at the firms that had pioneered the fundamental technologies behind wireless communications. Yet those proposing this testable hypothesis never actually tested it. Empirical researchers who subsequently did so found little to no evidence of “patent holdup.” Contrary to theory, real-world market conditions in the smartphone industry are characterized by constant lower quality-adjusted prices, robust market entry by new producers, and continuously increasing performance standards. Consumers in the US and around the globe have benefited from the virtuous feedback effect between secure property rights in new technologies, strong investment flows, and robust R&D output. The evidentiary burden surely rests on those who propose taking policy actions that would erode the property-rights foundation behind this technological and economic success story.

The smartphone industry is just one of multiple innovation markets that exhibit a positive relationship between reliable and effective patent rights, increased innovation, and economic growth. This evidence demonstrates a close relationship in the biopharmaceutical, medical device and certain information technology markets between patent protection and startups’ ability to secure financing for R&D and to undertake the costly commercial task of translating R&D into new products and services for consumers. This relationship is especially powerful in the case of startups that are often the source of breakthrough innovation. One empirical study shows that a startup with a patent more than doubles its chances of obtaining venture capital funding compared to a startup without a patent. Without a secure IP portfolio, venture capital and other investors will decline to support startups that often have few other legal or commercial mechanisms by which to secure their products and services against imitation by larger incumbents. For similar reasons, larger firms that specialize in R&D but do not have downstream production and distribution capacities require a secure IP portfolio to support a licensing infrastructure that generates the returns necessary to fund continued R&D that ultimately benefits downstream companies in the value chain and end-users in the marketplace.

Antitrust policy has long followed an error-cost approach that takes into account the relative costs associated with overenforcement (false positive errors) and underenforcement (false negative errors) of the antitrust laws. Consistent with this approach, the FTC’s policymaking and enforcement actions in innovation markets should be based on valid empirical evidence that makes it possible to weigh the likely costs and benefits of the agency’s actions.

This concern is especially relevant in evaluating the likelihood of consumer harm and the impact on innovation from patent infringement litigation. Like any form of civil litigation, patent litigation can be used for either legitimate or opportunistic purposes. Based on a limited body of evidence that suffers from substantial methodological shortcomings, antitrust agencies have issued statements and taken actions supporting blanket denials of the availability of injunctive relief for all patent owners who primarily license their technologies (“non-practicing entities”).

A broader empirical literature has looked more closely with rigorous analysis and uncovered a far more nuanced market and legal reality. First, no empirical study has demonstrated that patent owners’ requests for injunctive relief after findings of defendants’ infringement of their property rights have resulted systematically either in consumer harm or in slowing down the pace of technological innovation. Second, researchers have found that the “non-practicing entities” or “patent assertion entities” rubric encompasses a large number of business models that generate social gains by providing licensing and other mechanisms for undercapitalized individual inventors, startups, small firms, and universities. These innovators lack the commercial means to extract revenue from R&D that can generate valuable new products and services for consumers. Painting all of these entities with the same rhetorical broad brush threatens to unravel a rich ecosystem of inventors, startups, and entrepreneurs that rely on the legal backstop of injunctive relief to support markets in intellectual assets. Abusive litigation practices by a limited number of patent owners could and should be targeted surgically through fee-shifting and other standard tools available in all civil litigation. Again, regulatory intervention without a firm evidentiary basis runs the risk of harming consumer welfare by undermining the reliable and effective patent rights on which innovators, venture capitalists, startups, and other market participants rely in creating and expanding the innovation markets that benefit everyone.

In support, we attach an Appendix of articles that provide rigorous empirical studies and evidence-based analyses of IP-driven innovation markets, patent licensing, and patent litigation.

In conclusion, the FTC should continue to develop policies and undertake enforcement actions only with evidence of proven harms to consumers and with proper consideration of the costs in undermining reliable and effective IP rights that have consumer-welfare enhancing effects in the US innovation economy. A balanced consideration of the evidence on both harms and benefits is necessary to ensure balanced protection of innovators and consumers. We are confident that a commitment by the FTC to a program of evidence-based policy-making will lead to a vibrant, dynamic innovation economy supported by a secure foundation of IP rights that will continue to benefit consumers in the US and around the world.

Sincerely,

Kristina M. L. Acri

Associate Professor of Economics

The Colorado College

Jonathan Barnett

Professor of Law

USC Gould School of Law

Andrew Beckerman-Rodau

Professor of Law

Suffolk University Law School

Ronald A. Cass

Dean Emeritus,

Boston University School of Law

Former Vice-Chairman and Commissioner,

United States International Trade Commission

The Honorable Douglas H. Ginsburg

Senior Circuit Judge,

United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, and

Professor of Law,

Antonin Scalia Law School

George Mason University

Stephen Haber

A.A. and Jeanne Welch Milligan Professor

Stanford University

Christopher M. Holman

Professor of Law

UKMC School of Law

Keith N. Hylton

William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor

Boston University School of Law

David J. Kappos

Former Under Secretary of Commerce and Director

United States Patent & Trademark Office

Erika Lietzan

Associate Professor of Law

University of Missouri School of Law

The Honorable Paul Michel

Chief Judge (Ret.),

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

Damon C. Matteo

Course Professor

Tsinghua University in Beijing

Adam Mossoff

Professor of Law

Antonin Scalia Law School

George Mason University

Sean M. O’Connor

Boeing International Professor of Law

University of Washington School of Law

Kristen Osenga

Professor of Law

University of Richmond School of Law

Matthew L. Spitzer

Howard and Elizabeth Chapman Professor of Law

Northwestern University School of Law

Saurabh Vishnubhakat

Associate Professor of Law

Texas A&M University School of Law

Joshua D. Wright

University Professor,

Antonin Scalia Law School

George Mason University

Former Commissioner,

Federal Trade Commission

APPENDIX

Kristina M. L. Acri, née Lybecker, Economic Growth and Prosperity Stem from Effective Intellectual Property Rights, 24 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 865 (2017), http://georgemasonlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/24_4_Lybecker.pdf

Ashish Arora & Robert P. Merges, Specialized Supply Firms, Property Rights and Firm Boundaries, 14 Ind. & Corp. Change 451 (2005)

Jonathan H. Ashtor, Does Patented Information Promote Progress? (June 22, 2017), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2857697

Jonathan H. Ashtor, Opening Pandora’s Box: Analyzing the Complexity of U.S. Patent Litigation, 18 Yale J. L. & Tech. 217 (2016), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2736556

Jonathan M. Barnett, Antitrust Overreach: Undoing Cooperative Standardization in the Digital Economy (Nov. 2018), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3277667

Jonathan M. Barnett, Has the Academy Led Patent Law Astray?, 32 Berk. Tech. L. J. 1313 (2017), http://btlj.org/data/articles2017/vol32/32_4/Barnett_web.pdf

Jonathan M. Barnett, From Patent Thickets to Patent Networks: The Legal Infrastructure of the Digital Economy, 55 Jurimetrics J. 1 (2014), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2431917

Jonathan M. Barnett, Three Quasi-Fallacies in the Conventional Understanding of Intellectual Property, 12 Journal of Law, Econ. and Pol. 1 (2016), https://ssrn.com/abstract=265636

Christopher A. Cotropia, Jay P. Kesan & David L. Schwartz, Unpacking Patent Assertion Entities (PAEs), 99 Minn. L. Rev. 649 (2014), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2346381

Richard Epstein, F. Scott Kieff & Daniel F. Spulber, The FTC, IP, and SSOs: Government Hold-Up Replacing Private Coordination, 8 J. Comp. L. & Econ. 1 (2012), https://ssrn.com/abstract=1907450

Richard A. Epstein & Kayvan Noroozi, Why Incentives for Patent Hold Out Threaten to Dismantle FRAND and Why It Matters, 32 Berkeley Tech. L. J. (2018), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2913105

Joan Farre-Mensa, Deepak Hegde, & Alexander Ljungqvist, What Is a Patent Worth? Evidence from the U.S. Patent ‘Lottery’ (USPTO Econ. Working Paper No. 2015-5, Mar. 2017), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2704028

Alexander Galetovic & Stephen Haber, The Fallacies of Patent Holdup Theory, 13 J. Comp. L. & Econ. 1 (2017), https://academic.oup.com/jcle/article/13/1/1/3060409

Alexander Galetovic, Stephen Haber, & Lew Zaretzki, An Estimate of the Average Cumulative Royalty Yield in the World Mobile Phone Industry: Theory, Measurement and Results (Feb. 7, 2018), https://hooverip2.org/working-paper/wp18005

Alexander Galetovic, Stephen Haber, & Ross Levine, An Empirical Examination of Patent Hold Up, 11 J. Comp. L. & Econ. 549 (2015), https://academic.oup.com/jcle/article/11/3/549/800066

Douglas H. Ginsburg, Koren W. Wong-Ervin, & Joshua Wright, The Troubling Use of Antitrust to Regulate FRAND Licensing, CPI Antitrust Chronicle (Oct. 2015), https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/assets/Uploads/GinsburgetalOct-151.pdf

Douglas H. Ginsburg, Taylor M. Ownings, & Joshua D. Wright, Enjoining Injunctions: The Case Against Antitrust Liability for Standard Essential Patent Holders Who Seek Injunctions, The Antitrust Source (Oct. 2014), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2515949

Stuart J.H. Graham & Ted Sichelman, Why Do Start-Ups Patent?, 23 Berk. Tech. L. J. 1063 (2008), https://ssrn.com/abstract=1121224

Stuart J.H. Graham & Saurabh Vishnubhakat, Of Smart Phone Wars and Software Patents, 27 J. Econ. Persp. 67 (2013), http://ssrn.com/abstract=2291603

Kirti Gupta, Technology Standards and Competition in the Mobile Wireless Industry, 22 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 865 (2015), http://www.georgemasonlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/GuptaTechStandards.pdf

Stephen Haber, Patents and the Wealth of Nations, 23 George Mason L. Rev. 811 (2016), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2776773

Christopher M. Holman, The Critical Role of Patents in the Development, Commercialization and Utilization of Innovative Genetic Diagnostic Tests and Personalized Medicine, 21 B.U. J. Sci. & Tech. L. 297 (2015), http://www.bu.edu/jostl/files/2015/12/HOLMAN_ART_FINALweb.pdf

Ryan T. Holte, Trolls or Great Inventors: Case Studies of Patent Assertion Entities, 59 St. Louis U. L.J. 1 (2014), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2426444

Albert G.Z. Hu and I.P.L. Png, Patent Rights and Economic Growth: Evidence from Cross-Country Panels of Manufacturing Industries, 65 Oxford Econ. Papers 675 (2013), https://academic.oup.com/oep/article-abstract/65/3/675/2362113

Keith N. Hylton, Patent Uncertainty: Toward a Framework with Applications, 96 B.U. L. Rev. 1117 (2016), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2714434

Zorina Khan, Trolls and Other Patent Inventions: Economic History and the Patent Controversy in the Twenty-First Century, 21 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 825 (2014), http://www.georgemasonlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Khan-WebsiteVersion.pdf

Scott Kieff & Anne Layne-Farrar, Incentive Effects from Different Approaches to Holdup Mitigation Surrounding Patent Remedies and Standard-Setting Organizations, 9 J. Comp. L. & Econ. 1091 (2013), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274522003_Incentive_effects_from_different_approaches_to_holdup_mitigation_surrounding_patent_remedies_and_standard-setting_organizations

Bruce H. Koboyashi & Joshua D. Wright, Federalism, Substantive Preemption, and Limits on Antitrust: An Application to Patent Holdup, 5 J. Comp. L. & Econ. 1 (2009), https://ssrn.com/abstract=1143602

Bruce H. Koboyashi & Joshua D. Wright, The Limits of Antitrust and Patent Holdup: A Reply to Cary et al., 78 Antitrust L.J. 505 (2012), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2704591

Anne Layne-Farrar, Why Patent Holdout is Not Just a Fancy Name for Plain Old Patent Infringement, CPI North American Column (Feb. 2016), https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/NorthAmerica-Column-February-Full.pdf

Anne Layne-Farrar, Patent Holdup and Royalty Stacking Theory and Evidence: Where Do We Stand After 15 Years of History?, OECD Intellectual Property and Standard Setting (Nov. 18, 2014), http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DAF/COMP/WD%282014%2984&doclanguage=en

Anne Layne-Farrar, Moving Past the SEP RAND Obsession: Some Thoughts on the Economic Implications of Unilateral Commitments and the Complexities of Patent Licensing, 21 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 1093 (2014), http://www.georgemasonlawreview.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/06/Layne-Farrar-Website-Version.pdf

Gerard Llobet & Jorge Padilla, The Optimal Scope of the Royalty Base in Patent Licensing, 59 J. L. & Econ. 45 (2016), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2417216

Alan C. Marco & Saurabh Vishnubhakat, Certain Patents, 16 Yale J.L. & Tech. 103 (2013), http://ssrn.com/abstract=2324538

Kevin R. Madigan & Adam Mossoff, Turning Gold to Lead: How Patent Eligibility Doctrine is Undermining U.S. Leadership in Innovation, 24 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 939 (2017), http://georgemasonlawreview.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/11/24_4_Madigan_Mossoff_2.pdf

Keith Mallinson, Don’t Fix What Isn’t Broken: The Extraordinary Record of Innovation and Success in the Cellular Industry under Existing Licensing Practices, 23 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 967 (2016), http://www.georgemasonlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/Mallinson-FINAL.pdf

Keith Mallinson, Theories of Harm with SEP Licensing Do Not Stack Up, IP Fin. Blog (May 24, 2013), http://www.ip.finance/2013/05/theories-of-harm-with-sep-licensing-do.html

Ronald J. Mann, Do Patents Facilitate Financing in the Software Industry?, 83 Tex. L. Rev. 961 (2005), https://ssrn.com/abstract=510103

Jorge Padilla & Koren W. Wong-Ervin, Portfolio Licensing to Makers of Downstream End-User Devices: Analyzing Refusals to License FRAND-Assured Standard-Essential Patents at the Component Level, 62 The Antitrust Bulletin 494 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1177/0003603X17719762

Kristen Osenga, Formerly Manufacturing Entities: Piercing the “Patent Troll” Rhetoric, 47 Conn. L. Rev. 435 (2014), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2476556

Kristen Osenga, Ignorance Over Innovation: Why Misunderstanding Standard Setting Operations Will Hinder Technological Progress, 56 U. Louisville L. Rev. 159 (2018). https://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications/1502/

Kristen Osenga, Sticks and Stones: How the FTC’s Name-Calling Misses the Complexity of Licensing-Based Business Models, 22 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 1001 (2015), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2834140

Jonathan D. Putnam & Tim A. Williams, The Smallest Salable Patent-Practicing Unit (SSPPU): Theory and Evidence (Sept. 2016), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2835617

David L. Schwartz & Jay P. Kesan, Analyzing the Role of Non-Practicing Entities in the Patent System, 99 Cornell L. Rev. 425 (2014), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2117421

Gregory Sidak, What Aggregate Royalty Do Manufacturers of Mobile Phones Pay to License Standard-Essential Patents?, 1 Criterion J. Innovation 701 (2016), https://www.criterioninnovation.com/articles/sidak-aggregate-royalty-to-license-standard-essential-patents.pdf

Gregory Sidak, The Antitrust Division’s Devaluation of Standard-Essential Patents, 104 Geo. L.J. Online 48 (2015), https://georgetownlawjournal.org/articles/161/antitrust-division-sdevaluation-of/pdf

Gregory Sidak, Testing for Bias to Suppress Royalties for Standard-Essential Patents, 1 Criterion J. on Innovation 301 (2016), https://www.criterioninnovation.com/articles/sidak-bias-to-suppress-sep-royalties.pdf

Matthew Spitzer, Patent Trolls, Nuisance Suits, and the Federal Trade Commission, 20 N.C. J.L. & Tech. 75 (2018), https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncjolt/vol20/iss1/2

Daniel F. Spulber, Standard Setting Organizations and Standard Essential Patents: Voting and Markets, Econ. J. (2018), https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12606

Daniel F. Spulber, Patent Licensing and Bargaining with Innovative Complements and Substitutes (June 2018), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2818008

Daniel F. Spulber, How Patents Provide the Foundation of the Market for Inventions, 11 J. Comp. L. & Econ. 271 (2015), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2487564

David J. Teece, Competing Through Innovation: Technology Strategy and Antitrust Policies (Edward Elgar, 2013), https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/competing-through-innovation

David J. Teece, Edward F. Sherry, & Peter Grindley, Patents and ‘Patent Wars’ in Wireless Communications: An Economic Assessment, 95 Comm. & Strat. 85 (2014), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2603751

David J. Teece & Edward F. Sherry, On Patent ‘Monopolies’: An Economic Re-Appraisal, CPI Antitrust Chronicle (Apr. 2017), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2962208

Joanna Tsai & Joshua D. Wright, Standard Setting, Intellectual Property Rights, and the Role of Antitrust in Regulating Incomplete Contracts, 80 Antitrust L.J. 157 (2015), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2467939

Gregory J. Werden & Luke M. Froeb, Why Patent Hold-Up Does Not Violate Antitrust Law (Sep. 24, 2018), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3244425

Joshua D. Wright, SSOs, FRAND, and Antitrust: Lessons from the Economics of Incomplete Contracts, 21 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 791 (2014), http://www.georgemasonlawreview.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/06/Wright-Website-Version.pdf

Ziedonis, Rosemarie H. and Bronwyn H. Hall, The Effects of Strengthening Patent Rights on Firms Engaged in Cumulative Innovation: Insights from the Semiconductor Industry, in Gary D. Libecap (ed.), Entrepreneurial Inputs and Outcomes: New Studies of Entrepreneurship in the United States (2001).

On December 17, 2018, CPIP Senior Scholars Adam Mossoff and Kristen Osenga joined an amicus brief written on behalf of seven law professors by Professor Adam MacLeod, a CPIP Thomas Edison Innovation Fellow for 2017 and 2018 and a member of CPIP’s growing community of scholars. The brief, which was filed in Return Mail Inc. v. United States Postal Service, asks the Supreme Court to reverse the Federal Circuit’s determination that the federal government has standing to challenge the validity of an issued patent in a covered business method (CBM) review before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).

On December 17, 2018, CPIP Senior Scholars Adam Mossoff and Kristen Osenga joined an amicus brief written on behalf of seven law professors by Professor Adam MacLeod, a CPIP Thomas Edison Innovation Fellow for 2017 and 2018 and a member of CPIP’s growing community of scholars. The brief, which was filed in Return Mail Inc. v. United States Postal Service, asks the Supreme Court to reverse the Federal Circuit’s determination that the federal government has standing to challenge the validity of an issued patent in a covered business method (CBM) review before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).

The petitioner, Return Mail, owns a patent for a method of processing mail that is returned as undeliverable. After the Postal Service refused to take a license, Return Mail sued it for “reasonable and entire compensation” in the Court of Federal Claims under Section 1498(a). Thereafter, the Postal Service filed a petition at the PTAB seeking CBM review, arguing that several claims were unpatentable. Return Mail contested the ability of the Postal Service to petition for CBM review, arguing that it is not a “person” who has been “sued for infringement” within the meaning of Section 18(a)(1)(B) of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act of 2011 (AIA). Over a forceful dissent by Judge Newman, the Federal Circuit upheld the PTAB’s determination that the Postal Service has standing to challenge Return Mail’s patent before the PTAB.

The amicus brief written by Prof. MacLeod argues that the Federal Circuit was wrong to hold that the federal government could be treated as a “person” who has been charged with infringement. The brief points out that the federal government cannot be liable for patent infringement since it has sovereign immunity. Instead, the government has the authority to take a license whenever it pleases under its eminent domain power—so long as it pays just compensation to the patentee. The Federal Circuit classified the Postal Service’s appropriation as infringement, thus bringing it within Section 18(a)(1)(B) of the AIA. But, as the amicus brief notes, an infringement is an unlawful exercise of the exclusive rights granted to a patentee. The government may have exercised Return Mail’s patent rights, but it did not do so unlawfully, and as such it is not in the same position as a private party who has been charged with infringement.

The Summary of Argument is copied below, and the amicus brief is available here.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The United States Postal Service (“Postal Service”) wants to be a sovereign power. It also wants not to be a sovereign power. It exercises the right of sovereignty to take patent rights by the power of eminent domain. But it wants to stray beyond the inherent limitations on sovereign power so it can contest the validity of patent rights in multiple venues and avoid the duty to pay just compensation for a license it appropriates.

At the same time, the Postal Service asserts the private rights of an accused infringer to initiate a covered business method review (“CBM”) proceeding though it is immune from the duties and liabilities of an infringer. In other words, the Postal Service is trying to have it both ways, twice. It wants the powers of sovereignty without its disadvantages, and the rights of a private party without exposure to liability.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit erroneously ruled that the Postal Service can exercise both the sovereign power to initiate an administrative patent review, which is entrusted to the Patent Office, and the sovereign power to appropriate patent rights by eminent domain, which is delegated to federal agencies that may exercise patent rights. Congress separated those powers and delegated them to different agencies for important constitutional and jurisprudential reasons. Furthermore, the Federal Circuit ruled that the Postal Service can be both immune from liability for infringement and vested with the powers of an accused infringer. It did this by misstating what a “person” is within the meaning of United States law and by reading unlawfulness out the definition of “infringement,” as the Petitioner explained in its Petition.

In the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act of 2011 (“AIA”), Pub. L. No. 112-29, 125 Stat. 284, Congress created alternatives to Article III litigation concerning patent validity—inter partes review (“IPR”), post-grant review (“PGR”), and covered business method proceedings (“CBM”). IPR, PGR, and CBM proceedings are intended as alternatives to inter alia infringement actions in which an accused infringer might challenge patent validity. This suggests that the Government, which is immune from liability for infringement, is not a “person” with power to initiate an IPR, PGR, or CBM proceeding.

In jurisprudential terms, the Postal Service claims the powers and immunities of the legislative sovereign, who possesses the inherent power of eminent domain and is immune from liability for infringement. At the same time, the Postal Service tries to claim the powers of an accused infringer and so disavow the legal disadvantages of the sovereign. It cannot have both.

In fact, the Postal Service cannot infringe and cannot be charged with infringement. The sovereign who exercises the power of eminent domain and pays just compensation has acted lawfully, not unlawfully, and therefore has not trespassed against the patent. And the Postal Service must pay compensation when it appropriates a license to practice a patented invention. Vested patents are property for Fifth Amendment purposes, and the Government must pay for licenses taken from them, just as it pays for real and personal property that it appropriates.

To read the amicus brief, please click here.

By Kathleen Wills*

By Kathleen Wills*

On October 11-12, 2018, the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property (CPIP) hosted its Sixth Annual Fall Conference at Antonin Scalia Law School in Arlington, Virginia. The theme of the conference was IP for the Next Generation of Technology, and it featured a number of panel discussions and presentations on how IP rights and institutions can foster the next great technological advances.

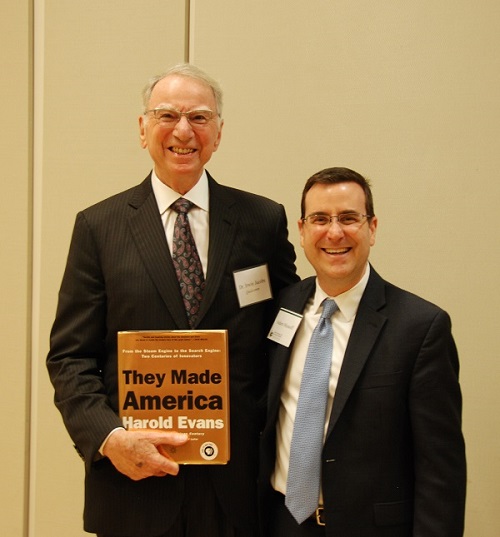

In addition to the many renowned scholars and industry professionals who lent their expertise to the event, the conference’s keynote address was delivered by Dr. Irwin M. Jacobs, founder of Qualcomm Inc. and inventor of the digital transmission technology for cell phones that gave birth to the smartphone revolution. The video of Dr. Jacobs’ keynote address, embedded just below, is also available here, and the transcript is available here.

After beginning his career as an electrical engineer and professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Dr. Jacobs’ vision for the future of wireless communications drove him to found his first company, Linkabit, in the late 1960s. In the years that followed, Dr. Jacobs led teams that developed the first microprocessor-based satellite modem and scrambling systems for video and TV transmissions. In 1985, Dr. Jacobs founded Qualcomm, which pioneered the development of mobile satellite communications and digital wireless telephony on the national and international stage.

Dr. Jacobs’ keynote address focused on intellectual property’s role in the development of technology throughout his 50-year career. He began his speech by discussing his background in electrical engineering and academia at MIT and at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). After publishing a textbook on digital communications, Dr. Jacobs explained that he then transitioned into consulting and started Linkabit, where he learned the importance of intellectual property.

Dr. Jacobs recounted how he later sold the company to start Qualcomm with the “mobile situation” of satellite communications on his mind. At Qualcomm, Dr. Jacobs wanted to break from the standard technology in favor of code-division multiple access (CDMA). CDMA had the potential to attract more users with a system that limited the total amount of interference affecting each channel, and it wasn’t long before Qualcomm was assigned the first patent on the new technology.

Qualcomm’s first product was Omnitracs, a small satellite terminal designed for communicating with dishes that led to the creation of a GPS system. Qualcomm’s patented GPS device used antenna technology to calculate locations based on information about the terrain, and it was very valuable to the company.

Using that source of income, Dr. Jacobs revisited CDMA at a time when the industry pursued time-division multiple access (TDMA) for supporting the shift to second-generation digital cellular technology. However, Dr. Jacobs knew that CDMA had the potential to support 10 to 20 times more subscribers in a given frequency band per antenna than TDMA. Within one year, Qualcomm built a demonstration of CDMA. At that time, the size of the mobile phone was large enough to need a van to drive it around!

Dr. Jacobs explained that commercializing the technology required an investment for chips, and it wasn’t long before AT&T, Motorola, and some other companies signed up for a license. Qualcomm decided to license every patent for the next “n” years to avoid future licensing issues and collect a small royalty. The industry eventually set up a meeting comparing TDMA to CDMA, and CDMA’s successful demonstration convinced the Cellular Telephone Industry Association to allow a second standard. A standards-setting process took place and, a year and a half later, the first standard issuance was completed in July of 1993.

Speaking on the push for CDMA, Dr. Jacob’s explained that there were “religious wars” in Europe because governments had agreed to only use an alternate type of technology. Nevertheless, CDMA continued to spread to other countries and rose to the international stage during talks about the third generation of cellular technology involving simultaneous voice and data transmissions. Dr. Jacobs visited the European Commissioner for Competition and eventually arranged an agreement with Ericsson around 1999 based on a strategic decision: instead of manufacturing CDMA phones in San Diego, there would be manufacturers everywhere in the world.

Selling the infrastructure to Ericsson, Qualcomm dove into the technology, funded by the licenses. The strategic decision to embed technology in chips in order to sell the software broadly has been Qualcomm’s business model ever since. Dr. Jacobs explained that since “we felt we had well-protected patents,” and had a steady income from the licenses, the team could do additional R&D. With that support, they were the first to put GPS technology into a chip and into a phone, developed the first application downloadable for the phone, and looked ahead at the next generation of technology.

Dr. Jacobs said that he’s often asked, “Did you anticipate where all of this might go?” To that question he replies, “Every so often.” Qualcomm was able to move the industry forward because of the returns generated through its intellectual property. Dr. Jacobs early realized that the devices people were carrying around everywhere were going to be very powerful computers, and that “it’s probably going to be the only computer most of us need several years from now.”

“Protecting intellectual property, having that available, is very critical for what was then a very small company being able to grow,” Dr. Jacobs said. Because Dr. Jacobs relied on secure intellectual property rights to commercialize and license innovative products, and in turn used income from licensing patents for R&D, Qualcomm was—and continues to be—able to prioritize high performance computing and to keep the cellular technology industry moving forward.

To watch the video of Dr. Jacobs’ keynote address, please click here, and to read the transcript, please click here.

*Kathleen Wills is a 2L at Antonin Scalia Law School, and she works as a Research Assistant at CPIP

By Kathleen Wills*

By Kathleen Wills*

The question whether patents are property rights is a continuing and hotly debated topic in IP law. Despite an abundance of scholarship (see here, here, here, here, and here) detailing how intellectual property (“IP”) rights have long been equated with property rights in land and other tangible assets, critics often claim that this “propertarian” view of IP is a recent development. Misconceptions and false claims about patents as property rights have been perpetuated in an echo chamber of recent scholarship, despite a lack of evidentiary support.

Unfortunately, these misleading arguments are now influencing important pharmaceutical patent debates. Specifically, a new push to devalue patent rights through the misapplication of an allegedly obscure and misunderstood statute, Section 1498 in Title 28 of the U.S. Code (“Section 1498”), is now being used to promote price controls. Arguments for this push have gained traction through a recent article whose flawed analysis has subsequently been promoted by popular media outposts. A better understanding of the nature of patents as property reveals the problems in this argument.

The history of Section 1498 clearly contemplates that patents are property subject to the Takings Clause, which reflects a long-standing foundation of patent law as a whole: Patents are private property. In an influential paper, Professor Adam Mossoff established that from the founding of the United States, patents have been grounded in property law theories. While some scholars today argue that the perception of patents began as monopoly privileges, this is only partially correct.

The arguments usually revolve around certain stated views of Thomas Jefferson, but they ignore that his position was actually a minority view at the time. Even when the term “privilege” was used, it reflected the natural rights theory of property that a person owns those things in which he invests labor to create, including labors of the mind. The term did not reflect a discretionary grant revocable at the will of the government. Thus, an issued patent was a person’s property, as good against the government as against anyone else.

To understand the majority perspective of courts in the nineteenth century, it is important to note that James Madison, the author of the Takings Clause, wrote that the “[g]overnment is instituted to protect property of every sort.” What types of property? Courts often used real property rhetoric in patent infringement cases, as seen in Gray v. James. By 1831, the Supreme Court believed that patent rights were protected just like real property in land was protected. In Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co., the Court established that patent rights represent legitimate expectations similar to property rights in land, which, in turn, are rights secured under the Takings Clause of the Constitution.

This understanding of patents reflected a stark break from the traditions in English law from which American law developed. In England, the “crown-right” granted the government the right to practice a patented invention wherever and however it pleased. In 1843, the Supreme Court in McClurg v. Kingsland explained that while England viewed a patent as “a grant” issued as a “royal favor,” which could not be excluded from the Crown’s use, the American system was intentionally different and patent rights were good against the government. This meant that Congress had to treat patents as vested property rights in the patent owner.

Justice Bradley enumerated this difference between the United States and England in James v. Campbell:

The United States has no such prerogative as that which is claimed by the sovereigns of England, by which it can reserve to itself, either expressly or by implication, a superior dominion and use in that which it grants by letters-patent to those who entitle themselves to such grants. The government of the United States, as well as the citizen, is subject to the Constitution; and when it grants a patent the grantee is entitled to it as a matter of right, and does not receive it, as was originally supposed to be the case in England, as a matter of grace and favor.

As an article by Professor Sean O’Connor explains, this change occasionally caused confusion in American courts when it came to patent owners seeking redress against unauthorized government use. The problem was that there was no single clear mechanism for suing the federal government for injunctive or monetary relief—in fact under sovereign immunity principles, in many cases the plaintiff could not sue the government. Various mechanisms such as implied or quasi contracts were used, but the varying nature of patentees—had they received some government funding leading to their invention or developed it purely outside of government support—complicated things further.

To provide a venue where citizens could sue the government for patent infringement and other claims, Congress created the Court of Claims in 1855. In 1878, the Court of Claims in McKeever v. United States explained that in the United States, patent rights secured the “mind-work which we term inventions,” authorized under the Copyright and Patent Clause in the Constitution. By explaining that patent rights derived from Article I in the Constitution, the Court of Claims suggested that patents were as important as other property rights and thus different from grants. Prof. O’Connor shows that the status of patents as property, and the recognition of this fact by the courts, solved much of the confusion over the history of American patent law.

The Supreme Court went on to affirm the Court of Claims’ decision to award damages to a patentee for an unauthorized governmental use of his patented invention. In United States v. Burns, the Court said that “[t]he government cannot, after the patent is issued, make use of the improvement any more than a private individual, without license of the inventor or making compensation to him.” In James v. Campbell, the Supreme Court echoed this idea when it held that patents confer owners an exclusive property in their invention, and that the government cannot use such an invention without just compensation any more than the government could appropriate land without compensation.

By 1881, it was clear that the courts recognized patents as property rights under constitutional protection from government takings, just like real property. With a strong historical record showing that the Supreme Court equated patents as protected property rights, a question remains: Where does the confusion today stem from?

As Prof. Mossoff explains, the confusion could come from misconstrued inferences of legislative intent regarding the Tucker Act (“Act”). The 1887 version of the Act did not address patents when giving the Court of Claims jurisdiction to hear claims arising from Constitution. This was used by the Federal Circuit in Zoltek Corp. v. United States to deny patents security under the Takings Clause. The Federal Circuit reasoned that patents weren’t constitutional private property. Judge Newman, however, dissented from the petition for rehearing en banc. She highlighted that “[a]lmost a century of precedent has implemented the right of patentees to the remedies afforded to private property taken for public use. There is no basis today to reject this principle.” (The Takings Clause analysis was subsequently vacated when the Federal Circuit eventually took the case en banc.)

An investigation of the Act’s legislative history also leads to a 1910 committee report (H.R. Rep. No. 61-1288), stating that the government’s unauthorized use of patents qualified as a taking. A few years after, the 1918 amendment adjusted the Act’s language to specifically allow patentees to sue the government for unauthorized uses of their property. Thus, the Tucker Act included patent claims in the kind of suits where the government’s unauthorized use was a constitutional issue, appropriately within the Court of Claims’ jurisdiction. Towards the end of the twentieth century, courts continued to hold that patents were constitutionally protected private property.

Modern cases have also confirmed that patents are property protected by the Takings Clause. Chief Justice Roberts, in Horne v. Department of Agriculture, used a patent case for the proposition that the Takings Clause extends to all forms of property, not just real property. Even in Oil States v Greene’s Energy, Justice Thomas went out of his way to assert that the Takings Clause still applies to patents, citing the same case cited by the Chief Justice in Horne.

There has always been a continuous understanding that patents are property, and thus, that Section 1498 is the eminent domain mechanism for the use of patents for the government’s own purposes. Popular media has recently misunderstood Section 1498, but the statute is not a price control statute as detailed in a previous post in this series. Additionally, forthcoming posts in this series will address other such misconceptions surrounding Section 1498.

*Kathleen Wills is a 2L at Antonin Scalia Law School, and she works as a Research Assistant at CPIP

By Adam Mossoff, Sean O’Connor, & Evan Moore*

By Adam Mossoff, Sean O’Connor, & Evan Moore*

The price of the miracle drugs everyone uses today is cause for concern among people today. The President has commented on it. Some academics, lawyers, and policymakers have routinely called for the government to “do something” to lower prices. The high prices are unsurprising: cutting-edge medical treatments are the result of billions of dollars spent by pharmaceutical companies over decades of research and development with additional lengthy testing trials required by the Food & Drug Administration. Earlier this year, though, the New York Times called for the government to use a federal law in forcing the sale of patented drugs by any private company to consumers in the healthcare market, effectively creating government-set prices for these drugs.

The New York Times proposal was prompted by an article in the Yale Journal of Law and Technology, which asserts that this law (known as § 1498) has been used by the federal government in the past to provide the public with lower-cost drugs. This claim—repeated as allegedly undisputed by the New York Times—is false. In fact, the proposal to use § 1498 for the government to set drug prices charged by private companies in the healthcare market would represent an unprecedented use of a law that was not written for this purpose.

Let’s first get clear on the law that the New York Times has invoked as the centerpiece of its proposal: § 1498 was first passed by Congress over a hundred years ago. It was a solution to a highly technical legal issue of how patent owners could overcome the government’s immunity from lawsuits when the government used their property without authorization. What ultimately became today’s § 1498 waived the federal government’s sovereign immunity against lawsuits, securing to patent owners the right to sue in federal court for reasonable compensation for unauthorized uses of their property.

This law resolved vexing legal questions about standing and jurisdiction, securing to patent owners the same right to constitutional protection of their property from a “taking” of their property by the government under the Fifth Amendment as all other property owners. This short summary makes clear that § 1498 is solely to provide compensation for government use of patented invention; it is neither a price control statute nor a general license for government agencies to intervene in private markets.

This is confirmed by the text of § 1498, which provides that when a patented invention is “used or manufactured by” the government, the patent owner is owed a “reasonable and entire compensation.” Thus, § 1498 acknowledges that the government has the power to use a patent for government use as long as it pays reasonable compensation to the patent owner. The predecessor statute was initially limited to direct government use of the invention. But in 1918 it was amended to cover government contractors as well. The issue was that patentees were suing and obtaining injunctions for infringement by private contractors, which slowed important production of war materials during World War One.

Just as the initial statute precluded an injunction against the government—providing only for “reasonable and entire compensation” as the sole remedy—the amended statute further shielded government contractors by placing the sole remedy for the latter’s infringement on the government as well. This makes sense given that the private company was working at the behest of the government itself. Thus, central to any such defense was that the contractor needed to show that it was infringing the patent on the “authorization and consent” of the government. And, just as for the government’s direct infringement, the contractor’s infringement was covered only to the extent it was for legitimate government use. Any private market use by the private company placed its infringing uses outside the statute and thus the company was fully liable for regular patent remedies, including injunctive relief.

The article published in the student-edited law journal that precipitated the New York Times proposal misconstrues § 1498 because it engages in an economic sleight of hand, characterizing pharmaceutical patents as an unwarranted tax paid by the public. The underlying argument is that drugs are expensive due to monopoly pricing and any drug sold above its basic cost of production represents economic deadweight loss. This argument ignores one of the key economic functions of the patent system, which is to secure the opportunity for innovators to recoup extensive costs in R&D expenditures and which are not reflected in costs of production themselves, such as the more than $2 billion in R&D spent by innovative pharmaceutical companies in creating a new drug.

The argument by the journal article thus applies to any patent (and has been made against all patents by other critics of the patent system), but the authors limit their proposal to cases of “excessive” prices for certain drugs, such as the cutting-edge, groundbreaking Hepatitis C treatment that ranges from $20,000-$90,000 for a 12-week treatment plan. Section 1498, they argue, should be used not just for the government’s own use of patented drugs for military personnel or other public employees, but for any infringement of the patent approved by the government in the name of providing lower prices to the public.

If the article authors and the New York Times had their way, the federal government would simply declare that a drug is too expensive and thus it would preemptively authorize any private company to make and sell the drug more cheaply. The pharmaceutical company would sue the companies for patent infringement, and the government would intervene under § 1498, claiming that these companies are essentially contractors acting at the behest of the government. Under the legal rules governing payment of “reasonable compensation” under § 1498 and payment of “just compensation” under the Fifth Amendment, the property owner receives the “fair market value” for the unauthorized use.

To the article authors and the New York Times this means a minimal royalty based off the mistaken premise that the price comparison would be retail price of the drug if it were not covered by a patent (like a generic). But instead, § 1498 procedures routinely rule that the government must compensate the patent owner the full measure of patent damages as would have been awarded in a regular patent infringement trial. Section 1498 does not provide a back door, cheaper “compulsory license” even for appropriate government use. The article authors and the New York Times would like to ignore the innovating pharmaceutical company’s R&D expenditures incurred beforehand and have the government compensate the company at significantly less than what it would receive under normal circumstances.

Aside from the flawed economic and legal argument underlying this price-control proposal, it represents an unprecedented use of § 1498, despite the claims by the article authors to the contrary. In the article, the authors assert that § 1498 was used exactly in this way in the 1950s and 1960s. But this is false: the federal government has never used § 1498 to authorize private companies to sell drugs to private consumers in the healthcare market in the United States. In these cases, the Department of Defense (“DoD”) relied on § 1498 to purchase military medical supplies from drug companies that infringed patents. Statements from agency heads during congressional hearings at the time confirm that the DoD, NASA, and the Comptroller General all understood the law as applying to procurement of goods for government use.

In other words, the government has never relied on or argued that § 1498 applies outside of the federal government procuring patented goods and services for its own use by its own agencies or officials. This is also true for government contractors: § 1498 shields a contractor’s infringement only while it is working directly for the federal government, and thus the private company cannot deliver the goods or services directly to private markets. If the contractor does this, its infringement falls outside the scope of § 1498, and it can be sued as a matter of private right directly for patent infringement under the patent laws.

Despite this significant commercial and legal difference between private companies working as contractors for the federal government and private companies selling products in the marketplace, the article authors (and thus the New York Times) claim otherwise. The New York Times, for instance, asserts that “In the late 1950s and 1960s, the federal government routinely used 1498 to obtain vital medications at a discount.” The New York Times further asserts that § 1498 “fell out of use” due mainly to the lobbying efforts of pharmaceutical companies. This is false. The historical record is absolutely clear that government agencies and courts have all applied § 1498 only to situations of government procurement and its own direct use. It has never been used to authorize private companies infringing patents for the sole purpose of selling the patented innovation to consumers in the free market.

The question then becomes whether § 1498 permits the federal government to simply declare certain patented products to be “too expensive” and this then justifies the government to indemnify private companies under its sovereign immunity to infringe the patent in selling the drug in the private healthcare market on the basis of this allegedly public purpose. Section 1498 has never been used in this way before, including when the government purchased drugs in the 1950s and 1960s. The authors of the article in the Yale Journal of Law and Technology claim they “recover this history and show how § 1498 can once again be used to increase access to life-saving medicines.” But § 1498 was never used in this way historically—the federal government has never used this law to permit private companies to sell drugs to private consumers in the private healthcare market. This proposal is an unprecedented use of a law in direct contradiction to its text and its 100+ years of application by federal agencies and courts.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the New York Times proposal is that it refers to § 1498 as an “obscure” provision of the patent law. First, it is not a statutory provision in the Patent Act, but rather is part of the federal statutes authorizing the judiciary to hear lawsuits. This underscores the early point that § 1498 was merely a technical fix to an unintended loophole existing since the 19th century that prevented, or at least complicated, patent owners suing the government for unauthorized uses by officials or agencies—even as the courts routinely opined that patents are property and that government should have to pay for their use. Second, while § 1498 may be “obscure” to the public at large, patent lawyers and government lawyers know this law very well. It is the bread and butter of government contract work and the legal basis of hundreds, if not thousands, of lawsuits against the federal government for over a century.

As the courts have long recognized, § 1498 is an eminent domain law. It provides a court with the authority to hear a lawsuit and award just compensation when the federal government or a person acting directly at its behest as its agent or contractor uses a patent without authorization. Section 1498 does not grant the government a new power to authorize infringement of a patent for the sole purpose of a company selling a product at a lower price in the market, effectively imposing de facto government price controls on drugs. The proposal in an academic journal and repeated by the New York Times to use § 1498 in this way is unprecedented. Even worse, it threatens the legal foundation of the incredible medical innovation in this country created by the promise to pharmaceutical companies of reliable and effective patent rights as a way to secure to them the fruits of their innovative labors.

*Evan Moore is a 2L at Antonin Scalia Law School, and he works as a Research Assistant at CPIP.

On October 11-12, 2018, CPIP hosted its Sixth Annual Fall Conference, IP for the Next Generation of Technology, at Antonin Scalia Law School, George Mason University, in Arlington, Virginia. Our conference addressed how IP rights and institutions can foster and support the next leap forward in technology that is about to break out into consumer products and services.

Without doubt, the highlight of our conference was the keynote address by Dr. Irwin M. Jacobs—the inventor of the digital transmission technology for cell phones that gave birth to the smartphone revolution and the founder of Qualcomm. Dr. Jacobs has been a luminary in the telecommunications industry for many years, and he delighted conference attendees with endearing stories and wonderful insights from his inventive and commercial activities over the years.

We hope you will enjoy Dr. Jacobs’ keynote address as much as we do!