By Devlin Hartline and Aditi Kulkarni*

[The “Invalidated” documentary will be screened this Friday, October 26, at 5:30 PM in Washington, D.C. To register for this free event, which features a presentation by Bunch O Balloons inventor Josh Malone among others, please click here.]

Imagine that you’re a father of eight children who puts everything on the line to bring your invention to the marketplace. After a successful Kickstarter campaign that brings in close to $1 million, you protect your invention by securing several patents on the innovative technology. Your invention is a huge market success, and sales exceed your wildest dreams. When the copycats come along, you think your patent rights will protect you. After all, that’s what the patent system is for. But you quickly realize that the system is stacked against you, the lone inventor, and it instead favors the large companies that willingly violate your rights for profit.

While this horror story may sound farfetched, it’s exactly what happened to Josh Malone, the inventor of Bunch O Balloons. And the unfortunate reality is that Malone is not the only inventor to be let down by the patent system that is meant to protect inventors from unscrupulous infringers. Thankfully, Malone is not taking things lying down. Not only is he fighting for his rights in the courts and at the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office—the very Office that granted him the rights in the first place—but he also has become a vocal activist fighting to reform the patent system. In fact, Malone is now telling his story in a new documentary entitled “Invalidated.” The full video, which prominently features CPIP Founder Adam Mossoff and runs about 50 minutes long, is available at both iTunes and Amazon.

You can watch the trailer here:

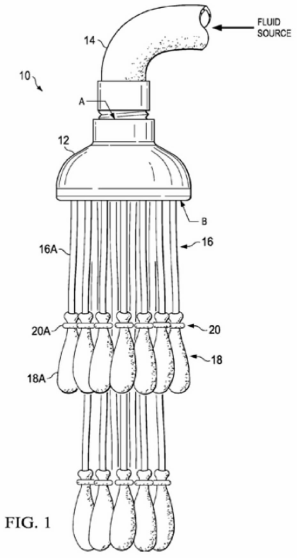

Inspired by childhood memories, Josh Malone invented Bunch O Balloons to solve a real-world problem. His invention allows anyone to fill and tie around 100 water balloons in just one minute. As a child, he spent days filling up hundreds of water balloons to play with his friends. Though he eventually stopped playing with balloons, the idea of finding a better way to play never left him. His idea finally materialized through a method to save his children’s time by filling several balloons at once. Malone burned the midnight oil perfecting his invention, and his family also invested their time and efforts backing his venture. After failing through several experiments and exhausting their savings, Malone finally succeeded with Bunch O Balloons.

Ready with the product’s final prototype embodying his invention, Malone shot a video for a Kickstarter campaign to advertise his product and to raise some much-needed funds. The campaign was a hit, bringing in close to $1 million. Malone was even interviewed on the Today Show, where he got into an impromptu water balloon fight with Carson Daly. The purchase orders then started pouring in from toy manufacturers and big retailers like Walmart. They were all interested in profiting from the competitive advantage they would get from Malone’s novel—and fun—invention.

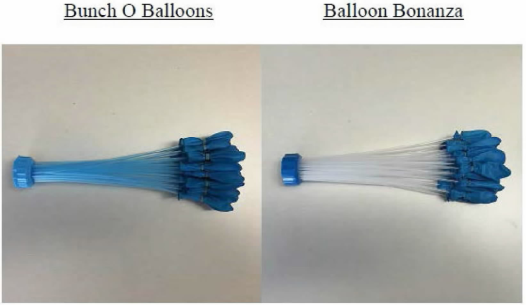

On realizing his invention’s strength and wanting to protect it from potential infringers, Malone filed several patent applications with the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO). While the patent applications were pending, Malone came to know that a product nearly identical to his own was being advertised and sold in the marketplace under the name, “Balloon Bonanza.” Investigating further, Malone realized that Telebrands, the marketing company that originated the “As Seen On TV” advertisements, had stolen his idea and begun selling knock-off versions of his invention.

Malone sued Telebrands in the Eastern District of Texas, seeking a preliminary injunction to prevent the marketer from further infringing his rights. The district court granted the injunction, agreeing with Malone that his patent was likely valid and infringed. Telebrands fought back, appealing the injunction to the Federal Circuit and again challenging the validity of Malone’s patent on indefiniteness and obviousness grounds. The Federal Circuit sided with Malone, holding that it was not clear error for the district court to conclude that he was likely to succeed on the merits. The Court of Appeals rejected Telebrands’ arguments as failing to raise a substantial question concerning the validity of Malone’s patent.

Telebrands also challenged the validity of Malone’s patent before the Patent Trial & Appeal Board (PTAB) in a post-grant review (PGR) proceeding. During the pendency of Telebrands’ appeal to the Federal Circuit on the preliminary injunction, the PTAB rendered its final written decision: Telebrands had shown by a preponderance of the evidence that Malone’s patent was invalid as indefinite. Of course, had the issue been decided in the district court, the mere preponderance standard would have been insufficient to overturn the presumably valid patent. But in the PTAB, the rules are different, and they favor challengers such as Telebrands that use the additional venue to game the system.

The Federal Circuit was well aware of the PTAB’s decision to the contrary when it upheld the district court’s determination that Malone was likely to succeed on merits in assessing the propriety of the preliminary injunction. In fact, it mentioned the PTAB proceedings in a footnote, noting that its decision was not binding and that it was nevertheless unpersuasive. When Malone subsequently appealed the PTAB loss, the Federal Circuit finally got its chance to directly address the PTAB’s decision on the merits. The Court of Appeals held that, even applying the PTAB’s more relaxed standard, Malone’s claims were not unpatentable for indefiniteness. The Federal Circuit thus made good on the earlier indications from both itself and the district court that Malone’s patent was indeed valid.

While Malone ultimately has been victorious so far, he’s been forced to spend millions of dollars protecting his rights. He reported in July of 2017 that he’d already spent $17 million, and that it might grow to as much as $50 million before it’s all through. That’s an insane amount of money for most lone inventors, and Malone is fortunate enough to have made enough revenue in sales to be able to afford it. Most people aren’t so lucky. And the battle for inventors is certainly far from over, especially when infringers with deep pockets can repeatedly play the game and wear down their victims in multiple forums. As Malone laments, “the PTAB simply encourages infringers like Telebrands to double down on the expense of litigation, rather than acquiescing to the adjudication by the District Court.”

It’s no wonder that, in his dismay, Malone joined other frustrated inventors to symbolically burn their patents outside of the USPTO in the summer of 2017. Malone’s story is a stereotype example of how the big infringers attempt to overwhelm the little guy by simply outspending them should they dare to challenge the wrong. Such gamesmanship at the expense of inventors is not the purpose of the PTAB. As Professor Mossoff notes in the documentary: “The original argument for why we needed the PTAB is that, every once in a while, there will be a mistakenly issued patent they shouldn’t have issued, and that these patents can clog the gears of the innovation economy. Unfortunately, what Congress created was a completely unrestrained, unrestricted agency whose job is to cancel patents.”

America’s Founders recognized that a stable and effective patent system is vitally important for the innovation ecosystem to thrive. American inventors like Josh Malone have made a significant difference in people’s lives, and the patent system exists to reward them for their efforts. Inventors should be able to trust that the patent system will be there to protect them when others trample on their rights. They need those rights to be meaningful in order to recoup their investments and to realize their just rewards. The Founders understood that benefiting inventors through such private gains would redound to the public benefit. But as Malone’s story demonstrates, we will need to make some changes to the patent system before the Founders’ vision can be fully realized.

*Aditi Kulkarni is working towards an LLM Degree in Intellectual Property at Antonin Scalia Law School, and she works as a Research Assistant at CPIP.

Earlier this year, CPIP’s Adam Mossoff and Kevin Madigan

Earlier this year, CPIP’s Adam Mossoff and Kevin Madigan  ARLINGTON, Virginia – August 22, 2018 – The Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property (

ARLINGTON, Virginia – August 22, 2018 – The Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property ( By

By  By

By  Today, Representatives Steve Stivers (R-OH) and Bill Foster (D-IL) introduced the Support Technology & Research for Our Nation’s Growth and Economic Resilience (STRONGER) Patents Act of 2018. This important piece of legislation will protect our innovation economy by restoring stable and effective property rights for inventors. This legislation mirrors a bill already introduced in the

Today, Representatives Steve Stivers (R-OH) and Bill Foster (D-IL) introduced the Support Technology & Research for Our Nation’s Growth and Economic Resilience (STRONGER) Patents Act of 2018. This important piece of legislation will protect our innovation economy by restoring stable and effective property rights for inventors. This legislation mirrors a bill already introduced in the  A group of judges, former judges and government officials, law professors and economists with expertise in antitrust law and patent law

A group of judges, former judges and government officials, law professors and economists with expertise in antitrust law and patent law