This post is one of a series in the #Innovate4Health policy research initiative.

By Jaci Arthur

By Jaci Arthur

Every year, more than 200 million cases of malaria are reported worldwide. It can often be mistaken for a less serious malady, as symptoms include “fever, chills, and flu-like illness.” If quickly identified, the disease is treatable. Yet more than 655,000 people, mostly children in sub-Saharan Africa, died from malaria in 2016.

Expeditious diagnosis of the disease can result in faster treatment and lower mortality rates. The patented Urine Malaria Test (UMT) developed by Dr. David Sullivan, a Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health professor and microbiologist, addresses this global challenge by offering a rapid, accurate, more convenient, and less expensive alternative to traditional laboratory testing. The UMT is also the first point-of-care (POC) test for malaria that does not require the use of trained personnel or a blood sample.

90% of all malaria-related deaths in 2015 occurred on the African continent. Much of this can be attributed to a lack of access to health services and personnel due to poverty, remoteness, and a general lack of healthcare infrastructure. According to a 2011 report, about 31% of Ethiopians live on less than $1.25 a day. Even when health services are free of charge, trips to medical facilities are quite costly for the average, rural African because patients will often have to take an entire day off from work to travel.

In Niger, a patient may have to walk more than four hours to receive medical treatment at an overcrowded, ill-equipped facility. Many people turn to presumptive diagnosis or self-medication at the first sign of a fever, resulting in widespread drug resistance and more expensive treatments. Meanwhile, others gamble on the chance it is simply a virus that will pass, never seeking diagnosis or treatment.

On average, there are 1.15 health workers for every 1,000 people in sub-Saharan Africa, with numbers as low as 0.4 physicians for every 10,000 people in countries like Chad. The few laboratories in rural areas that can identify diseases such as malaria are underfunded, short-staffed, and ill-equipped. Although there are several POC tests for malaria, most of them require trained personnel taking a blood sample. Having a proper diagnosis within twenty-four hours of the onset of symptoms can reduce the mortality rate, but such diagnosis is difficult for most Africans. All these factors lead to a deadly combination, especially for those in rural Africa.

Maryland-based Fyodor Biotechnologies was founded in 2008 by Nigerian biotechnologist Eddy Agbo specifically to address these problems. In 2009, the company was granted an exclusive worldwide license from Johns Hopkins University to research, develop, and commercialize the UMT.

As its name suggests, the UMT tests a patient’s urine, rather than blood, for “novel Plasmodium proteins,” and it provides results in less than twenty-five minutes, thus abating fears, eliminating the need for presumptive diagnosis, and reducing costly, lengthy, and unnecessary trips. Unlike other tests for malaria, the UMT can be taken at home and is as easy to use as an at-home pregnancy test. The UMT is currently priced at about two dollars each; however, Dr. Agbo intends for the price to be reduced once production increases.

Preclinical studies were conducted by researchers at Johns Hopkins University, and the UMT is currently in clinical validation. Fyodor intends to seek concurrent regulatory clearance from both the Nigerian National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Initial commercialization efforts will be focused in Dr. Agbo’s home country of Nigeria before expanding to other areas significantly affected by malaria. Nigeria accounts “for 25% of all malaria cases in the African region.” Testing is also currently underway at Fyodor Biotechnologies for a “second generation broad-based Urine Malaria Test (UMT-Broad),” which will be useful for detecting other types of infection.

Fyodor Biotechnologies stepped onto the global market specifically to meet the needs of people in malaria endemic regions and reduce the mortality rate associated with this treatable disease. The company relies heavily on its exclusive license to Johns Hopkins University’s patent, as research, development, and production of the UMT are currently its sole function.

Fyodor’s two-dollar, at-home test is the perfect counter to claims that intellectual property rights, specifically patents, result in expensive healthcare and a lack of access to necessary medical services. Intellectual property rights have made quick, efficient, low-cost, and convenient testing for malaria a reality.

The UMT provides an ideal example of how patented innovation can conquer global challenges. It is a reasonable, rapid, efficient, convenient, economical alternative to a system that cannot meet the needs of the rural poor. And it is a reminder that innovation and intellectual property rights can work together for the common good.

#Innovate4Health is a joint research project by the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property (CPIP) and the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF). This project highlights how intellectual property-driven innovation can address global health challenges. If you have questions, comments, or a suggestion for a story we should highlight, we’d love to hear from you. Please contact Devlin Hartline at jhartli2@gmu.edu.

In 2007, Ghanaian tech entrepreneur

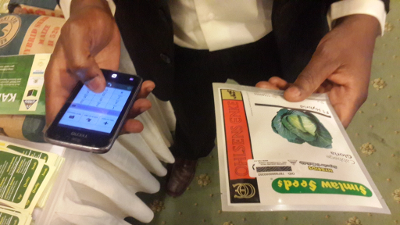

In 2007, Ghanaian tech entrepreneur  Through the combination of EarlySensor and Goldkeys, mPedigree’s innovative technology is facilitating the protection of both brand owners and consumers and ensuring that data collection and authentication mechanisms are leading to the safer distribution of medicines, cosmetics, seeds, and other essential products.

Through the combination of EarlySensor and Goldkeys, mPedigree’s innovative technology is facilitating the protection of both brand owners and consumers and ensuring that data collection and authentication mechanisms are leading to the safer distribution of medicines, cosmetics, seeds, and other essential products. By providing a dynamic link between consumers and manufacturers, mPedigree is making communications at the point of purchase routine and creating value for consumers, manufacturers, regulatory agencies, and sellers. A project ten years in the making, mPedigree is built on the recognition that protecting intellectual property—both mPedigree’s and its clients—can save lives.

By providing a dynamic link between consumers and manufacturers, mPedigree is making communications at the point of purchase routine and creating value for consumers, manufacturers, regulatory agencies, and sellers. A project ten years in the making, mPedigree is built on the recognition that protecting intellectual property—both mPedigree’s and its clients—can save lives.