By Kevin Madigan & Sean O’Connor

By Kevin Madigan & Sean O’Connor

This week, the Senate Judiciary Committee was to mark up a bill limiting patent eligibility for combination drug patents—new forms, uses, and administrations of FDA approved medicines. While the impetus was to curb so-called “evergreening” of drug patents, the effect would have been to stifle life-saving therapeutic innovations. Though the “No Combination Drug Patents Act”—reportedly to be introduced by Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC)—was wisely withdrawn at the last minute, it’s likely not the last time that such a misconceived legislative effort will be introduced.

An Exaggerated Response to a Disputed Theory

The bill would have established a presumption of obviousness for drug or biologic patent applications whose invention was a new: dosing regimen, method of delivery, method of treatment, or formulation. While there was a rebuttal provision where the claim covered a new treatment for a new indication or “increase[d] . . . efficacy,” the latter was almost certain to introduce years of uncertainty and litigation. Further, the bill would have covered a broader class than true combination drug patents, in which one active ingredient is combined with another or with a non-drug.

Like many recent legislative efforts, the amendment sought to address a perceived lack of affordability of prescription drugs. After praising the America Invents Act of 2011 and subsequent Supreme Court rulings for strengthening the US patent system, the bill claimed that rising drug prices have outpaced “spending on research and development with respect to those drugs.” In addition to applauding Supreme Court decisions that have injected unquestionable uncertainty into patentable subject matter standards, the amendment went on to blame high drug prices on continually overstated issues related to advanced drug patents.

According to critics, combination drug patents have granted drug makers unearned and extended protection over existing drugs or biological products. But, quite simply, when properly issued by the USPTO under existing patentability standards, these are new patents for new products or processes.

Combination patents have been maligned as anticompetitive, resulting in a “thicket” of patents that impedes innovation through transaction costs and other inefficiencies. Unfortunately, notwithstanding a lack of empirical evidence validating the harm of follow-on innovation patents, patent thicket rhetoric is now being echoed by the media, the academy, courts, and policy makers in a fraught attempt to fix drug pricing.

Reports (see here, here, here, and here) from leading antitrust experts and intellectual property scholars have detailed the value of incremental innovation and challenged the notion that patent thickets are a true threat to competition and innovation. These studies have exposed patent thicket claims—much like the “troll” narrative that for years infected patent law debates—as an empty strawman theory, the repetition of which has led to undue confidence in its accuracy. The reality is that what critics point to as problematic cases of combination patents are in fact infrequent outliers, strategically highlighted to discount evidence of the value of new and innovative drug uses and administrations.

A similar claim by those promoting the patent thicket narrative is that combination patents extend exclusivity on a drug for years beyond an initial patent term, thereby blocking generic entry in the market. But if an underlying drug has gone off patent, no follow-on or combination patent will prevent a generic drug company from producing the underlying formulation—it’s only the new formulation, use, or administration that is protected.

Vague, Yet Oddly Familiar Standards

The language of the Graham amendment asserted that because “numerous” combination patents “contain obvious product developments,” a restructuring of 35 USC 103 is necessary to combat patent thickets and achieve optimal drug pricing. Suggesting that 103 obvious standards for advanced drug development should include a presumption that the covered claimed invention and the prior art to which it relates would have been obvious, the legislation would have undermined a unitary system of patent law in favor of different standards for different fields of technology. It was a bold proposal, and it’s one that ignored the proven value of new drug formulations and methods of treatment.

While the amendment provided for a rebuttal to the presumption of obviousness, the language was ambiguous and likely to render the patent system even more unreliable than it already is. The proposed statute said that an applicant may rebut the presumption of obviousness if the covered claimed invention “results in a statistically significant increase in the efficacy of the drug or biological product that the covered claimed invention contains or uses.” It is unclear what would qualify as “statistically significant,” and proving this vague standard would be nearly impossible.

In order to show a “statistically significant increase in efficacy,” long and costly head-to-head clinical trials would be necessary. To be clear, this is not a standard required by the FDA for new drug approval, let alone patentability.

As if that wasn’t enough reason to reject the Graham amendment, the language was alarmingly similar to that of an Indian patent law statute that has been recognized by the US Trade Representative as a “major obstacle to innovators.” In 2005, in order to comply with the WTO’s Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement, India adopted for the first time patent protection for pharmaceuticals. Despite its recognition of IP rights in pharmaceuticals, India’s Act contains a troubling ambiguity in its Section 3(d), which requires an “enhanced efficacy” for known drugs in addition to the standard novelty, inventive step, and industrial applicability requirements.

India’s Section 3(d) has been invoked to reject patent protection for life-saving drug innovations, including Novartis’ landmark leukemia drug, Gleevec. Drug companies, government agencies, and policy makers have all recognized the threat to innovation that India’s patent law poses. In 2013, not long after the Novartis ruling, a bipartisan group of 40 Senators signed a letter to then Secretary of State John Kerry urging the state department to take action against India’s “deteriorating IP environment,” citing its willingness to “break or revoke patents for nearly a dozen lifesaving medications.”

Despite the widespread condemnation of India’s Section 3(d), the Graham amendment proposed adopting similarly indefinable standards to US patent law. While the language differed slightly—replacing “enhanced efficacy” with “increase in the efficacy”—it was no clearer, and implementation of this type of standard would only cause more confusion.

Protecting and Incentivizing Medical Innovation

Like most forms of innovation, the development of medicines and therapeutics is a process by which one builds and improves upon previous discoveries and breakthroughs. Sometimes those improvements are major advancements, but often they are incremental steps forward. In the pharmaceutical field, incremental or follow-on innovation frequently results in new therapeutic uses for existing drugs, which address serious challenges related to adverse effects, delivery systems, and dosing schedules. While they might not sound like medical breakthroughs on par with the discovery of penicillin, these advancements in the administration and use of pharmaceuticals improve public health and save lives.

Additionally, follow-on innovations are—and should remain—subject to the same patentability standards as any other technologies. Patents reward advancements that are novel, useful, and nonobvious, and our patent system has long recognized that patent claims are to be presumed patentable and nonobvious. The Graham amendment would have turned this established standard on its head, creating a separate and ill-defined hurdle for certain advancements in medicine.

The benefits of incremental innovation to public health and patients cannot be overstated. New formulations of malaria drugs, dosing regimens and delivery systems for AIDS patients, more efficient administrations of insulin for the treatment of diabetes, and developments in the treatment of cognitive heart disease have all been possible because of incremental innovation.

Imposing unjustified restrictions on the patentability of advancements like these would be disastrous for drug development, as the incentives that come with patent protection would be all but eliminated. Without the assurance that their innovative labor would be supported by intellectual property protection, pioneering drug developers would shift resources away from improving drug formulations and uses. The development of more effective treatments of some of the most devastating diseases would stall, as innovators would be unable to commercialize their products, recoup losses, or fund future research and development.

As critics continue to target myopically the patent system for a broader issue of drug prices in the American health care system, it’s likely not the last time that language like this will be proposed. In order to avoid the implementation of such ill-conceived standards into our patent laws, understanding what’s at stake is critical. The future of medical innovation depends on it.

Following the Supreme Court’s four decisions on patent eligibility for inventions under

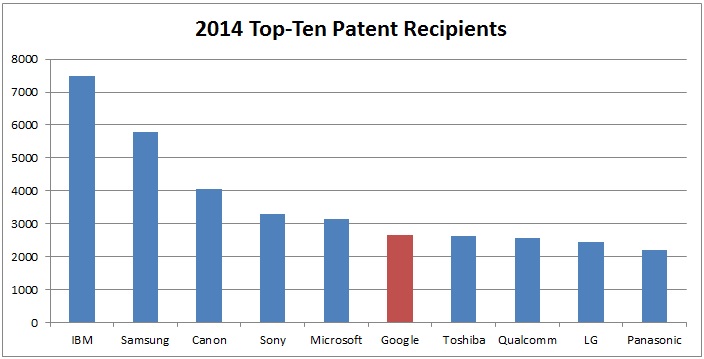

Following the Supreme Court’s four decisions on patent eligibility for inventions under  It is common today to hear that it’s simply impossible to search a field of technology to determine whether patents are valid or if there’s even freedom to operate at all. We hear this complaint about the lack of transparency in finding “prior art” in both the patent application process and about existing patents.

It is common today to hear that it’s simply impossible to search a field of technology to determine whether patents are valid or if there’s even freedom to operate at all. We hear this complaint about the lack of transparency in finding “prior art” in both the patent application process and about existing patents.