Cross-posted from the Mister Copyright blog.

As formats change and advances in technology continue to transform the way we listen to music, new methods of pirating content are never far behind. What started with the analog dubbing and bootlegging of cassettes forty years ago evolved with the digital age into CD burning and MP3 sharing, eventually leading to a chaotic illegal downloading landscape at the turn of the century that would force the music industry to develop novel anti-piracy efforts and distribution models. Digital streaming services have since taken over as the preferred way to consume music, boasting over 100 million subscribers in 2016—a number that recently surpassed the total number of Netflix streaming video subscribers.

As formats change and advances in technology continue to transform the way we listen to music, new methods of pirating content are never far behind. What started with the analog dubbing and bootlegging of cassettes forty years ago evolved with the digital age into CD burning and MP3 sharing, eventually leading to a chaotic illegal downloading landscape at the turn of the century that would force the music industry to develop novel anti-piracy efforts and distribution models. Digital streaming services have since taken over as the preferred way to consume music, boasting over 100 million subscribers in 2016—a number that recently surpassed the total number of Netflix streaming video subscribers.

A Fast Growing Threat

Despite this substantial base of paying customers and affordable monthly subscription rates, many are choosing to bypass legitimate services by “ripping” songs from streaming platforms, which involves recording, converting, and saving songs to downloadable file. It sounds complicated, but the internet is teeming with free apps and programs that make the ripping process easy, and its popularity has prompted some in the industry to flag it the fastest growing form of music piracy.

Stream ripping has existed for about ten years, with the digital performance rights organization Sound Exchange recognizing its dangers in 2007. But, as a Billboard magazine article from the same year noted, “even the music industry concedes that the impact of stream ripping is minimal.” The article goes on to explain the inefficient nature of ripping software and the inability of users to search internet radio services—which were at the time were not yet on-demand—for their desired content. It was similar to listening to terrestrial radio with a blank cassette tape ready and waiting for the song you want to be played in order to record it. Needless to say, times have changed and now on-demand streaming services and advanced stream recording technology have made ripping a very real threat to copyright holders and creators.

A survey by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) found that three in ten internet users had engaged in stream ripping over a six-month period in 2016. A similar 2016 study by MUSO, a leading content protection and piracy data specialist, measured a 60% increase in visits to stream ripping sites in one year from 2015 to 2016. This growing popularity is made more troubling by the fact that a predominantly younger audience is involved, with the IFPI survey finding that 49% of internet users between the ages of 16 and 24 regularly engage in stream ripping to acquire music. Though these numbers are already concerning, a forthcoming IFPI report is expected to show increases in stream ripping activity across the board.

Like most websites and programs that enable copyright infringement, ripping services make money from advertising based on the high levels of traffic they attract. And, nearly a year ago, a report from the RIAA estimated that traffic to the top 30 stream ripping sites topped 900 million in one month alone. It’s difficult to imagine that, in a year that has seen little progress in shutting down these ripping services, this number of monthly visitors wouldn’t have increased significantly. Making matters worse for artists and rights owners, unlike the illegal copies of songs or albums that permeate file sharing sights which can be identified and tagged to aid with takedown notices, these ripped versions are copied directly from the source, rendering them untraceable.

While different stream-ripping programs can record data from any number of streaming services, many developers have focused their attention on YouTube, where infringing content is rampant. Because YouTube is free and full of both licensed music videos and user generated content that often features unauthorized, full versions of copyrighted songs, it’s become an attractive destination for those who want to rip music but don’t want to pay to join a streaming service like Spotify or Apple Music.

YouTube-mp3.org

In 2016, a group of major record labels sued the operators of a stream ripping service based in Germany whose program was directed to the “rapid and seamless” copying of sound recordings from YouTube. YouTube-mp3.org is one of the most popular stream ripping tools available online, with 303.8 million visitors to its website in 2016 (making it the 141st most visited website globally). Users are attracted to its service not only because it’s free and doesn’t require an account, but because it’s incredibly easy to use. One simply pastes the YouTube URL in a search box and clicks a button that automatically converts the video’s audio track to an MP3 that can be stored on any number of devices.

According to the complaint, YouTube-mp3.org is guilty of direct, contributory, and vicarious copyright infringement, as well as inducement based on their blatant promotion of the stream ripping of copyright protected songs. Describing the nature of stream ripping in general, and YouTube-mp3.org specifically, the complaint warns:

“The scale of stream ripping, and the corresponding impact on music industry revenues, is enormous. Plaintiffs are informed and believe, and on that basis allege, that tens, or even hundreds, of millions of tracks are illegally copied and distributed by stream ripping services each month. And YTMP3, as created and operated by Defendants, is the chief offender, accounting for upwards of 40% of all unlawful stream ripping that takes place in the world.”

The complaint also alleges that YouTube-mp3.org circumvents technological protection measures (TPMs) that YouTube has implemented to prevent the very copying the program facilitates, thereby violating Section 1201(a) of the Copyright Act. Discussing the circumvention, the complaint explains:

“More specifically, Defendants’ service descrambles a scrambled work, decrypts an encrypted work, or otherwise avoids, bypasses, removes, deactivates, or impairs a technological measure without the authority of Plaintiffs or YouTube.”

The complaint looks to enjoin not only YouTube-mp3.org, but also all third parties—including web-hosting services and domain name registries—through which the Defendants infringe copyrights. As of the time of this post, the lawsuit had been stalled due to difficulties in serving the international defendants, but stake holders on all sides will continue to monitor the case closely.*

The Future of Music Piracy

According to the IFPI survey, stream ripping’s rapid growth has seen it bypass pirate site downloading and other forms of streaming as the most popular way to steal music. One reason for the shift to ripping may be the increasingly focused offensive against established torrent sites like the Pirate Bay and Kickass Torrents. But also contributing to the rise of ripping is the compatibility of the programs with mobile devices, which MUSO explains “is a key insight into the longer-term stream ripping trend.” The study identifies Brazil, Mexico, and Turkey as countries where mobile stream ripping is the most prevalent and connects this popularity to the quickly expanding smartphone markets. These accessible mobile interfaces provide a younger audience not only with the portability they want, but also with the ability to listen to music offline, which can be essential in countries with limited internet infrastructure.

Like the file sharing programs and torrent sites that came before it, stream ripping technology is not inherently illegal. But, like Grokster and IsoHunt, many of the most popular ripping services—which display prominently in Google search results for “stream ripping software”—were developed to facilitate piracy and are actively inducing copyright infringement. Also like these now defunct websites, YouTube-mp3.org tries to make the argument that it’s merely an intermediary and immune from liability based on 512(c) safe harbor provisions of the DMCA. On its website, YouTube-mp3.org claims that, “[d]ifferent from other services, the whole conversion process will be performed by our infrastructure and you only have to download the audio file from our servers.” By hosting the content on its own servers at the direction of a user, YouTube-mp3.org attempts to cast itself as a passive intermediary, and exposing it as a piracy-inducing bad actor is imperative to deter the development and promotion of similar services dedicated to copyright infringement.

With the music industry’s widespread commitment to the streaming model, ripping is a threat to legitimate services that must be confronted by both the creative industries and the platforms that distribute music. Thankfully, platforms like Soundcloud, Spotify, and YouTube have a stake in the fight against ripping, as they ultimately want users to watch videos and listen to music over and over on their websites where they are subject to advertisements, rather than steal content and leave. Whereas tech companies and platforms may not have had as much to lose when it came to file sharing and illegal downloading, stream ripping stands to affect not only rights owners, but also the tech industry that is increasingly involved in the creation and distribution of copyrighted content.

*On September 4, 2017, it was reported that the RIAA and Youtube-mp3.org had reached a settlement in which Youtube-mp3.org would shut down indefinitely, hand over its domain, and pay an undisclosed amount to the RIAA.

This Saturday, the world will be treated to one of the most hyped events in the history of sports when “The Notorious” Conor McGregor and Floyd “Money” Mayweather Jr. meet in Las Vegas to become (even more) rich while ostensibly also participating in a boxing match. The bout marks the first foray into boxing by a champion mixed martial artist—McGregor—at the height of his career, and is made even more compelling by the fact that he’ll be facing one of the greatest boxers of all time in Mayweather Jr.—albeit somewhat past his prime. The seemingly endless prefight activities have included an over-the-top press tour full of provocative trash talk, celebrity-attended training sessions, and a preventative effort by Showtime—the network airing the fight—to quash the inevitable flood of unauthorized streams that will pop up during what is predicted to be the

This Saturday, the world will be treated to one of the most hyped events in the history of sports when “The Notorious” Conor McGregor and Floyd “Money” Mayweather Jr. meet in Las Vegas to become (even more) rich while ostensibly also participating in a boxing match. The bout marks the first foray into boxing by a champion mixed martial artist—McGregor—at the height of his career, and is made even more compelling by the fact that he’ll be facing one of the greatest boxers of all time in Mayweather Jr.—albeit somewhat past his prime. The seemingly endless prefight activities have included an over-the-top press tour full of provocative trash talk, celebrity-attended training sessions, and a preventative effort by Showtime—the network airing the fight—to quash the inevitable flood of unauthorized streams that will pop up during what is predicted to be the  Last week, the United States Court for the Southern District of New York entered a

Last week, the United States Court for the Southern District of New York entered a  As digital piracy shifts away from torrent downloads and towards

As digital piracy shifts away from torrent downloads and towards  By Mandi Hart

By Mandi Hart In a recent essay responding to a divisive critique of his book, Justifying Intellectual Property, Robert Merges makes clear from the start that he won’t be pulling any punches. He explains that the purpose of his essay,

In a recent essay responding to a divisive critique of his book, Justifying Intellectual Property, Robert Merges makes clear from the start that he won’t be pulling any punches. He explains that the purpose of his essay,  The House Judiciary Committee today

The House Judiciary Committee today  Counterfeit medicines sold under a product name without proper authorization are a serious threat to global public health. Classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as substandard, spurious, falsely labelled, falsified and counterfeit (

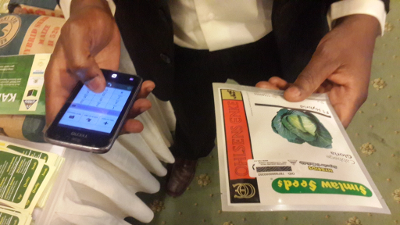

Counterfeit medicines sold under a product name without proper authorization are a serious threat to global public health. Classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as substandard, spurious, falsely labelled, falsified and counterfeit ( In 2007, Ghanaian tech entrepreneur

In 2007, Ghanaian tech entrepreneur  Through the combination of EarlySensor and Goldkeys, mPedigree’s innovative technology is facilitating the protection of both brand owners and consumers and ensuring that data collection and authentication mechanisms are leading to the safer distribution of medicines, cosmetics, seeds, and other essential products.

Through the combination of EarlySensor and Goldkeys, mPedigree’s innovative technology is facilitating the protection of both brand owners and consumers and ensuring that data collection and authentication mechanisms are leading to the safer distribution of medicines, cosmetics, seeds, and other essential products. By providing a dynamic link between consumers and manufacturers, mPedigree is making communications at the point of purchase routine and creating value for consumers, manufacturers, regulatory agencies, and sellers. A project ten years in the making, mPedigree is built on the recognition that protecting intellectual property—both mPedigree’s and its clients—can save lives.

By providing a dynamic link between consumers and manufacturers, mPedigree is making communications at the point of purchase routine and creating value for consumers, manufacturers, regulatory agencies, and sellers. A project ten years in the making, mPedigree is built on the recognition that protecting intellectual property—both mPedigree’s and its clients—can save lives. One year ago, domain name registry Donuts, Inc. and the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) entered into an agreement termed the Trusted Notifier Program in a joint effort to combat piracy. The voluntary initiative “introduced a new way to work towards mitigation of clear and pervasive cases of copyright infringement,” and according to

One year ago, domain name registry Donuts, Inc. and the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) entered into an agreement termed the Trusted Notifier Program in a joint effort to combat piracy. The voluntary initiative “introduced a new way to work towards mitigation of clear and pervasive cases of copyright infringement,” and according to