By Devlin Hartline & Kevin Madigan

How did the world’s wealthiest nations grow rich? The answer, according to Professor Stephen Haber of Stanford University, is that “they had well-developed systems of private property.” In Patents and the Wealth of Nations, recently published in the CPIP Conference issue of the George Mason Law Review, Haber explains the connection: Property rights beget trade, trade begets specialization, specialization begets productivity, and productivity begets wealth. Without a foundation of strong property rights, economic development suffers. But does the same hold true for intellectual property, particularly patents? Referencing economic history and econometric analysis, Haber shows that strong patents do indeed make wealthy nations.

How did the world’s wealthiest nations grow rich? The answer, according to Professor Stephen Haber of Stanford University, is that “they had well-developed systems of private property.” In Patents and the Wealth of Nations, recently published in the CPIP Conference issue of the George Mason Law Review, Haber explains the connection: Property rights beget trade, trade begets specialization, specialization begets productivity, and productivity begets wealth. Without a foundation of strong property rights, economic development suffers. But does the same hold true for intellectual property, particularly patents? Referencing economic history and econometric analysis, Haber shows that strong patents do indeed make wealthy nations.

Before diving into the history and analysis, Haber tackles the common misconception that patents are different than other types of property because they are monopolies: “It is not, as some IP critics maintain, a grant of monopoly. Rather, it is a temporary property right to something that did not exist before that can be sold, licensed, or traded.” The simple reason for this, Haber notes, is that a patent grants a monopoly only if there are truly no substitutes, but this is almost never the case. Usually, there are many substitutes and the patent owner has no market power. And the “fact that patents are property rights means that they can serve as the basis for the web of contracts that permits individuals and firms to specialize in what they do best.”

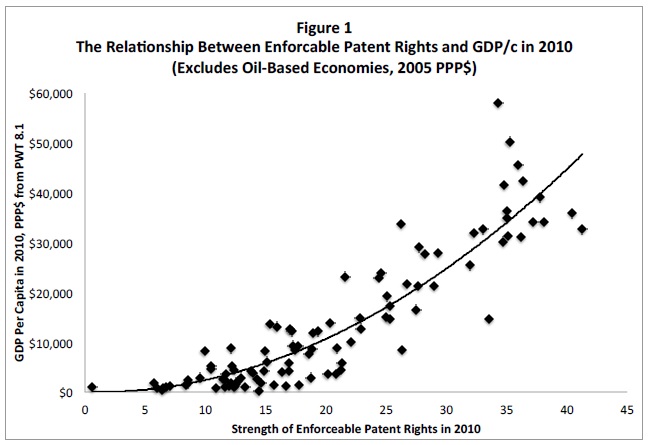

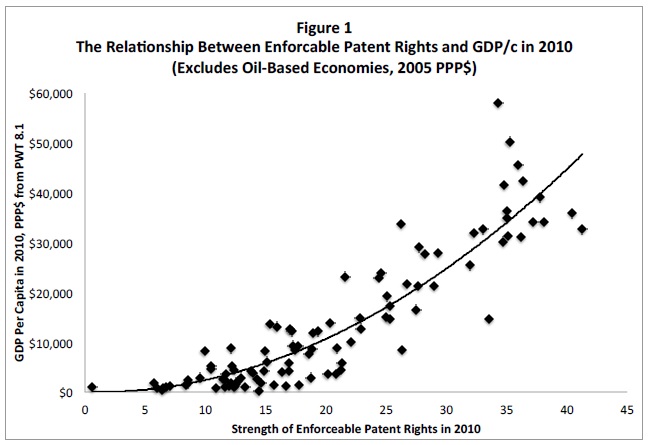

Turning back to his claim that strong patents make wealthy nations, Haber presents data showing the relationship between the strength of enforceable patent rights and the level of economic development across several different countries. The results are remarkably clear: “there are no wealthy countries with weak patent rights, and there are no poor countries with strong patent rights.” The following figure shows how GDP per capita increases as patent rights get stronger:

Of course, while it’s clear that patent strength and GDP per capita are related, it’s possible that the causality runs the other way. That is, how do we know that an increase in GDP per capita doesn’t foster an environment where patents tend to be stronger? This is where the evidence from economic historians and econometric analysts comes into play. Exploring what economic history has to tell us about the impact of patent laws on innovation, Haber asks whether the Industrial Revolution was bolstered by the British patent system and whether the United States emerged as a high-income industrial economy because of the U.S. patent system.

To the first question, Haber notes that the consensus among historians is that “from at least the latter half of the eighteenth century, the patent system promoted the inventive activity associated with the Industrial Revolution.” He then cites the recent book by Sean Bottomley that carefully shows how “many of the changes to Britain’s patent laws and their enforcement—the requirement for detailed specifications, patents conceived as property rights, the emergence of patent agents—all preceded, rather than followed, the onset of industrialization.” Haber also cites a research paper by Petra Moser, which finds that countries in the nineteenth century with weak patent systems trailed both Britain and the United States in technological development.

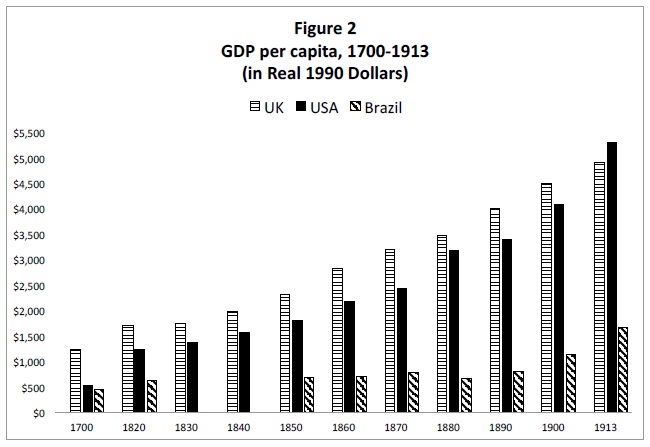

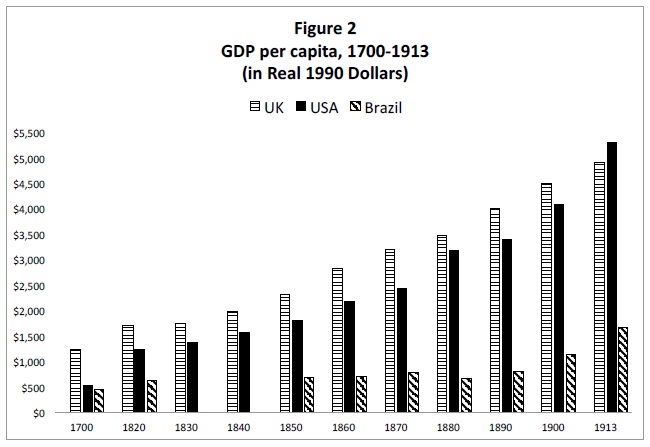

Moving to the United States, Haber notes that three generations of economic historians have agreed that just after it gained independence, the country’s strong patent system played a pivotal role in fomenting the remarkable industrial developments that soon followed. After pointing out that the United States was the first country to call for a patent system in its Constitution, Haber compares the GDP per capita for the United States, Britain, and Brazil from 1700 to 1913. The following figure shows just how quickly the agrarian American colonies caught up with, and ultimately surpassed, Britain in GDP per capita, while the GDP per capita of Brazil, a country that became independent at about the same time but had no patent system, stagnated:

As the figure shows, the GDP per capita in the United States and Brazil were less than half that of Britain in 1700, and by 1913, the United States had overtaken Britain as both countries left Brazil far behind. Noting that “there is uniformity of views among economic historians that the U.S. patent system played a large role” in this success, Haber provides specifics examples of improvements upon the British patent system that contributed to it, including broad access to property rights in technology through low fees and a routine and impersonal application process under the Patent Act of 1790. He goes on to highlight the importance of major reforms to the U.S. patent system introduced in the Patent Act of 1836, including the examination process that “reduced concerns third parties might have had about a patent’s novelty, thereby facilitating the evolution of a market for patented technologies.”

The second half of the nineteenth century saw the development of an active market for inventions in the United States, leading to the emergence of a class of specialized and independent inventors as well as patent brokers, patent agents, and patent attorneys, who would connect the inventors with manufacturers looking to buy or license new technologies. While some of these intermediaries were derided, much like the “patent trolls” of the twenty-first century, as “patent sharks,” Haber contends that this market for inventions played a critical role in the emergence of new industrial technologies and centers: “[O]ne would be hard pressed to make the case that patents in the nineteenth century, or the intermediaries who represented their inventors, did anything but facilitate the rapid development of American manufacturing.”

Haber then shifts his focus to econometric analysis, examining the different ways that economic scholars research the relationship between patent rights and economic progress in different countries over a period of time. He stresses that accurate econometric estimation of causal relationships is a relatively young area of inquiry requiring considerable care. He uses the example of a widely-cited study by Josh Lerner, which looks at “whether the strengthening of patents affects the rate of change of innovation in an economy within a two-year window after a patent reform.” Haber points out that many changes neither begin nor end so quickly. With laser technology, for example, “follow-on innovations” have developed “over decades, not two-year windows,” and Lerner’s study thus discounts much innovation.

Looking at studies that utilize a “very long time dimension,” Haber cites one finding that “there is a significant positive effect of patent laws on innovation rates” and another finding that “patent intensive industries in countries that improve the strength of patents experience faster growth in value added than less patent-intensive industries in those same countries.” Haber praises a recent study by Jihong Zhang, Ding Du, and Walter G. Park, who “not only find that there is a positive relationship between the strength of enforceable patent rights and innovation in developed economies, but that that relationship holds for underdeveloped economies as well.”

In sum, Haber states that “there is a critical mass of multi-country studies” that leads to two conclusions:

First, there is a causal relationship between the strength of patent rights and innovation. Second, this relationship is non-linear: there are threshold effects such that stronger patent rights positively impact innovation once a society has already reached some critical level of economic development. The reason for the non-linearity probably resides in the fact that innovation is not just a product of the strength of patent rights, but of other features of societies, which are necessary complements, that tend to be absent at low levels of economic development.

Finally, Haber looks at whether the innovation landscape of the twenty-first century is somehow so different that the lessons from economic history and econometric analysis no longer apply. In particular, he questions whether the emergence of patent licensing firms, sometimes called “patent assertion entities” or “PAEs,” and the alleged strategic behavior of “patent holdup” with standard-essential patents (SEPs) are really new features of the U.S. patent system that might hinder innovation. Haber concludes that the evidence shows that neither PAEs nor patent holdup is hindering innovation. In fact, there’s little reason to think that patent holdup even exists.

Haber takes on the recent study by James Bessen and Michael Meurer, which claims that PAEs are a new phenomenon that “constitute a direct tax on innovation” to the tune of “$29 billion per year.” This claim has been rebutted, Haber notes, by scholars such as B. Zorina Khan, whose recent study shows that many great inventors of the nineteenth century were themselves PAEs. Haber further cites the recent paper by David L. Schwartz and Jay P. Kesan that carefully demonstrates fundamental problems with Bessen and Meurer’s methodology, including selection bias, the conflation of “costs” with “transfers,” the lack of a benchmark for comparison, and the failure to even consider the benefits of PAE activity.

Turning to patent holdup, Haber points out that products have long been comprised of numerous patented innovations, and he cites a recent paper by Adam Mossoff showing that there’s nothing “new about firms whose sole source of revenue comes from the licensing of essential patents.” As to evidence that innovation is hindered by patent holdup, Haber notes that the “theoretical literature” says it’s possible, but the “evidence in support of this theory, however, is largely anecdotal.” Haber then cites his recent study with Alexander Galetovic and Ross Levine, which looks at the “extensive economics literature on the measurement of productivity growth” and shows that “SEP holders” are not able “to negotiate excessive royalty payments” as predicted by the patent holdup theory.

In conclusion, Haber acknowledges that while “no single piece of evidence” should “be viewed as dispositive,” it’s certainly quite “telling that the weight of evidence from two very different bodies of scholarship, employing very different approaches to evidence—one based on mastering the facts of history, the other based on statistical modeling—yield the same answer: there is a causal relationship between strong patents and innovation.” Haber then challenges the naysayers to make their case: “Evidence and reason therefore suggest that the burden of proof falls on those who claim that patents frustrate innovation.” Given the copious evidence showing that strong patents make wealthy nations, the IP critics have their work cut out for them.

For a PDF version of this post, please click here.

CPIP has published a tribute to Judge Giles S. Rich by Professor John F. Witherspoon. Prof. Witherspoon is Director Emeritus, Intellectual Property Program, Antonin Scalia Law School. Prof. Witherspoon’s career in government, academia, and private practice spans more than fifty years.

CPIP has published a tribute to Judge Giles S. Rich by Professor John F. Witherspoon. Prof. Witherspoon is Director Emeritus, Intellectual Property Program, Antonin Scalia Law School. Prof. Witherspoon’s career in government, academia, and private practice spans more than fifty years. In celebration of World Intellectual Property Day on April 26, 2017, the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property (CPIP) today joined with the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) to launch “

In celebration of World Intellectual Property Day on April 26, 2017, the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property (CPIP) today joined with the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) to launch “

How did the world’s wealthiest nations grow rich? The answer, according to Professor Stephen Haber of Stanford University, is that “they had well-developed systems of private property.” In

How did the world’s wealthiest nations grow rich? The answer, according to Professor Stephen Haber of Stanford University, is that “they had well-developed systems of private property.” In