The following post comes from Cala Coffman, a 2L at Scalia Law and Research Assistant at C-IP2.

At the recent C-IP2 conference entitled IP on the Wane: IP on the Wane: Examining the Impacts as IP Rights Are Reduced, one panel discussed the current state of copyright law, the pressures it has come under in recent years, and their differing perspectives on how the digital world is shaping copyright. Topics of discussion included enforcement techniques, trends in fair use, and the impact of evolving technology on copyright.

At the recent C-IP2 conference entitled IP on the Wane: IP on the Wane: Examining the Impacts as IP Rights Are Reduced, one panel discussed the current state of copyright law, the pressures it has come under in recent years, and their differing perspectives on how the digital world is shaping copyright. Topics of discussion included enforcement techniques, trends in fair use, and the impact of evolving technology on copyright.

Panelists were Clark Asay (Professor of Law at Brigham Young University J. Reuben Clark Law School), Orit Fischman-Afori (Professor of Law at The Haim Striks School of Law, College of Management Academic Studies (COLMAN)), Terry Hart (General Counsel, Association of American Publishers (AAP)), and Karyn A. Temple (Senior Executive Vice President & Global General Counsel, (Motion Picture Association)), and the session was moderated by Sandra Aistars (Clinical Professor, George Mason University, Antonin Scalia Law School; Senior Fellow for Copyright Research and Policy; and Senior Scholar at C-IP2).

Professor Fischman opened the panel by proposing a reconsideration of criminal enforcement for copyright claims. After reviewing current avenues for civil copyright enforcement, including the newly established Copyright Claims Board in the Copyright Office, Digital Millennium Copyright Act, and civil enforcement in federal court including the opportunity for statutory damages, Professor Fischman suggested that criminal copyright enforcement actions seem to be on the decline and should not be a focus of enforcement efforts. Rather, greater attention should be devoted to civil enforcement. Recently, the U.S. Sentencing Commission reported that criminal Copyright and Trademark cases have dropped from 475 cases in 2015 to 137 cases in 2021.

Over the past two decades, several enforcement mechanisms have been introduced to address the challenges authors face enforcing their copyrights in the digital world. These include the Digital Millennium Copyright Act in 1998, the Digital Theft Deterrence Act of 1999, and the Copyright Alternatives in Small-Claims Enforcement Act of 2020, which improved access to enforcement for small creators by creating a new administrative forum with simplified proceedings in the Copyright Office. Small copyright claims can be pursued there with or without the assistance of counsel. While these civil enforcement mechanisms are effective, they have not been without criticism.

Ultimately, Professor Fischman argued that the combination of civil and criminal enforcement frameworks creates a powerful enforcement mechanism for author’s rights. As we consider the current state of IP rights, criminal enforcement is becoming less meaningful overall, in her opinion.

Next, Professor Asay presented three recent empirical studies examining trends in copyright litigation.

The first study indexed fair use cases from 1991 to 2017. In this study, Professor Asay examines the scope of fair use analysis in copyright infringement cases and finds a “steady progression of both appellate and district courts adopting the transformative use paradigm, with modern courts relying on it nearly ninety percent of the time.” The study finds that at the Federal Circuit Court level, in cases where transformative use was asserted, 48% were found to be transformative, and 91% of transformative uses were found to be fair use. Professor Asay states that “fair use is copyright law’s most important defense to claims of copyright infringement,” but as courts increasingly apply transformative use doctrine, he finds that “it is, in fact, eating the world of fair use.”

The second study Professor Asay presented analyzed over 1000 court opinions from between 1978 and 2020 that used a substantial similarity analysis. In this study, Professor Asay finds first that courts rely on opinions from the Second and Ninth circuits “more than any other source in interpreting and applying the substantial similarity standard.” The study also breaks down trends within the two-step substantial similarity analysis. On the first step, Professor Asay finds that “courts mostly decide this first prong . . . as a matter of whether defendant’s had access to the plaintiff’s work, and they mostly favor plaintiffs.” On the second step, he finds “significant heterogeneity” in analyzing improper appropriation of a plaintiff’s work. He states that “no dominant means exist for resolving this question” and “the data also suggest that one of the keys to winning, for either defendants or plaintiffs, is the extent to which the court engages with and discusses copyright limitations.”

The third study, which is forthcoming, examines DMCA Section 1201 litigation. DMCA Section 1201 prohibits attempts to circumvent technological measures used to control access to a copyrighted work.17 U.S.C. § 1201. This study encompasses 205 cases and 209 opinions, and Professor Asay said during the panel that “the most interesting finding in this study is that there’s not much section 1201 litigation.” Although the DMCA has been in force for nearly twenty-five years, less than one appellate decision is made per year on average. The study also finds that “the most litigated subject matter” (over every other subject matter the study coded for) is software.

Ms. Temple discussed how new technologies, techniques, and distribution methods are constantly requiring courts to re-evaluate how authorship rights function in a digital landscape. She likewise commented on the challenges courts seem to face in appropriately drawing distinctions between derivative uses of copyrighted works that should require a license from the author, and transformative uses that are permissible under the affirmative defense of fair use.

Ms. Temple cited the numerous briefs in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (including the Motion Picture Association’s) that note that the transformative use test is becoming the sole criteria courts use to determine fair use. Indeed, the MPA’s brief cited to Professor Asay’s study on transformative use (Is Transformative Use Eating the World?) to support the petitioner’s assertion that “in practice, the transformativeness inquiry is virtually always dispositive of the fair use question.” In closing, Ms. Temple stated that although we may be “waning” in how courts see fair use, Warhol presents a chance to correct the fair use analysis and steer it away from infringing on the derivative work rights of authors.

Finally, Mr. Hart presented on potential threats to authorship rights and the concomitant harms to consumer interests in the e-book arena. Mr. Hart’s perspective was that as businesses, copyright industries legitimately have profit-motivated goals, but happily, their ability to meet these goals is directly tied to the “ultimate goal” of promoting science and the useful arts and thus is beneficial to society as a whole. Mr. Hart stated that “the good news, if we think copyright [protections are] waxing, is that . . . the legal framework both in the United States and internationally recognizes [the] principles” that allow copyright owners to take advantage of and divide their exclusive rights. However, digitization may pose a threat to the ability to license rights as the copyright owner desires, as digital copying and transmission greatly increases risk of infringement of e-books.

The e-book market is unique, according to Mr. Hart, in that authors may be particularly vulnerable to digital threats when “digital copies are completely indistinguishable from the originals, and so they would be competing directly with the copyright owner’s primary markets.” Furthermore, he stated that “threats to the ability of copyright owners . . . to pursue rational choices in how they market and distribute their works can be just as harmful as straight up piracy.”

Mr. Hart characterized the e-book market as a thriving, sustainable economy. E-books have been popular for over a decade now, and there are a “variety of licensing models [available] . . . that continue to evolve to meet both the needs of publishers and libraries.” Mr. Hart stated, “the evidence shows that this is a well-functioning market.” He said that “Overdrive, which is the largest e-book aggregator, reported that in 2021 there was over half a billion check-outs of library e-books worldwide, and the pricing is, in my view, fair and sustainable.” Additionally, Mr. Hart said, “Overdrive also reported . . . that the average cost per title for libraries declined in 2021, and libraries have been able to significantly grow their e-book collections . . . with collection budgets that, when you’ve adjusted for inflation, have essentially been flat the entire time.”

One of the major threats to authorship rights in the e-book market, in Mr. Hart’s view, is the rise of Controlled Digital Lending (CDL). While this theory is currently being litigated in Hachette Book Group v. Internet Archive, Mr. Hart posits that we are only a few steps from a full-blown digital first-sale doctrine, which could have widespread harms throughout copyright for many types of authors. Many amicus briefs in the Internet Archive case have identified this potential harm, as well. According to Hart, the Copyright Alliance brief, for example, stated that a ruling in favor of CDL would have extremely widespread economic harms for authors.

The second threat Mr. Hart identified comes from recent propositions at the state level that would introduce compulsory licenses for e-books. These proposed laws would outlaw limitations on e-book licenses offered to libraries and allow states to dictate what states believe are “reasonable” pricing for e-book licenses. A flaw in both the arguments for CDL and for compulsory e-book licensing, as Mr. Hart sees it, is that both approaches treat the mere exercise of a copyright owner’s exclusive right as unfair and, if accepted, would be dangerous encroachments on authorship rights.

Ultimately, while the panelists identified significant concerns in the existing copyright regime, they were hopeful about the future of authorship rights, reflecting that even if the protections for copyright law had “waned” in certain respects in recent years, and certain rights remain in peril, there are opportunities for education as courts confront the significant changes that accompany an increasingly digital landscape.

By Liz Velander

By Liz Velander

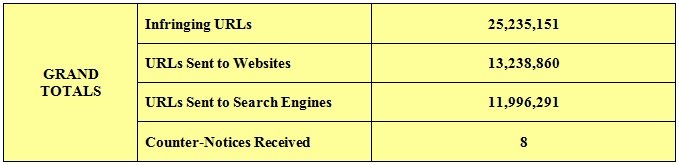

In 2013, CPIP published a policy brief by Professor Bruce Boyden exposing the DMCA notice and takedown system as outdated and in need of reform.

In 2013, CPIP published a policy brief by Professor Bruce Boyden exposing the DMCA notice and takedown system as outdated and in need of reform.

The Second Circuit’s recent opinion in

The Second Circuit’s recent opinion in