By Jason Lee Guthrie

For the Center for Intellectual Property x Innovation Policy blog, in fulfillment of obligations for the Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship

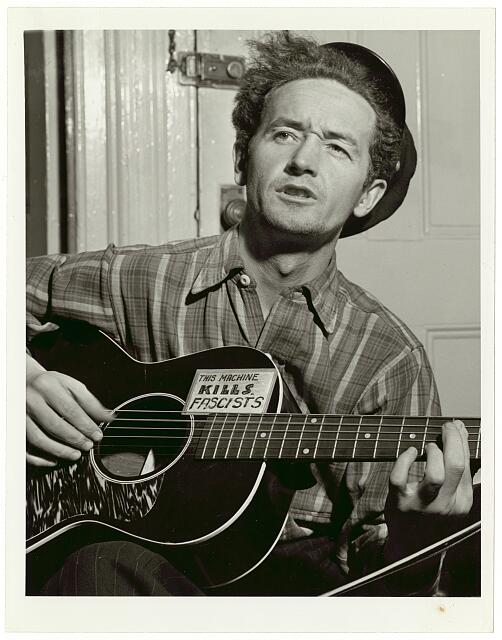

In early 1940, Woody Guthrie was on the road to New York City, and he was tired. Tired of traveling. Tired of the cold. Tired of having to hobo and hitchhike his way across America (again). He nearly froze to death in a Pennsylvania snowstorm along the way. He eventually made it to New York, though, alive but exhausted.

He was also tired of hearing Kate Smith’s patriotic anthem “God Bless America” on the radio. It had been an instant hit since its debut more than a year prior, but its ubiquity bothered Guthrie as did its use of religious imagery to inspire nationalist feeling. He was so tired of hearing it that when he finally got to New York he wrote his own song in response. Entitled “God Blessed America,” the song’s first three verses were an artistic rendering of his recent travels across “golden valleys” and “diamond deserts.” The fourth verse shifted somewhat in tone, though, and perhaps revealed something about Guthrie’s philosophical outlook:

Was a big high wall there / That tried to stop me

A sign was painted / Said: Private Property

But on the back side / It didn’t say nothing

God blessed America for me

“This Land” in Court

This song would eventually replace the line “God blessed America for me” with “This land was made for you and me” and change its title to “This Land Is Your Land.” The song’s development has been discussed in previous scholarship.[1] Here, I’ll focus on revisions only insofar as they relate to its copyright claim. The validity of this claim has received significant scholarly attention in recent years and even spilled over into public discourse as the copyright has been challenged in court. Research that I conducted while completing a Thomas Edison Innovation Law and Policy Fellowship revealed important details that can reframe scholarly discourse about the copyright in “This Land,” and may inform legal arguments if it is challenged again.[2]

As of this writing, the most recent litigation occurred in 2016 when the law firm of Wolf Haldenstein Adler Freeman & Herz filed a complaint on behalf of the band Satorii against The Richmond Organization (TRO), current publishers of “This Land” and other Guthrie works.[3] In 2015, the same firm successfully litigated a high profile case against Warner/Chappell Music, Inc. that established “Happy Birthday” in the public domain.[4] Buoyed by this success, the firm hoped to similarly invalidate the copyright claim in both “This Land” and the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.”[5] While the cases involving “Happy Birthday” and “We Shall Overcome” were relatively clear-cut, the facts of the copyright claim in “This Land” are more complicated and warrant an in-depth look.

Writing – and Protecting – “This Land”

Having a song undergo several rounds of revision was a normal part of Guthrie’s creative process. Also common to Guthrie’s process was the practice of pairing original lyrics with an established melody.[6] “This Land” is an example of this practice as the melody line and chord progression are based on an old Carter Family song entitled “Little Darling, Pal of Mine,” which itself was based on a gospel hymn entitled “Oh My Loving Brother.”[7]

The original lyric sheet for “This Land” evidences its evolution as lines from the first draft are crossed out and replaced with new ones.[8] The earliest known recording of the song was made in the mid-1940s with producer Moe Asch, and by that time the references to “God Bless America” had been dropped.[9] It was recorded again in the late 1940s and a third time in 1951.[10] As initiates into the byzantine world of music copyright will know, however, copyright in these specific sound recordings is distinct from a copyright in the words and music of the song itself.

“This Land” debuted on the radio in the mid 1940s as merely one song in Guthrie’s vast repertoire. One of the ways that musical acts on the radio generated income at this time was to sell songbooks to listeners that contained the sheet music for tunes they heard on the air.[11] Guthrie had been creating such songbooks for years by this point, and in 1945 he created one that included “This Land” along with other titles. Mimeographed from a handmade manuscript and advertised at a selling price of 25 cents, this document included an explicit copyright claim on both its cover and first page.[12] Such a notice met the basic requirements for claiming copyright at the time. Moreover, Guthrie was generally aware of these requirements and had made efforts to comply with them before.[13]

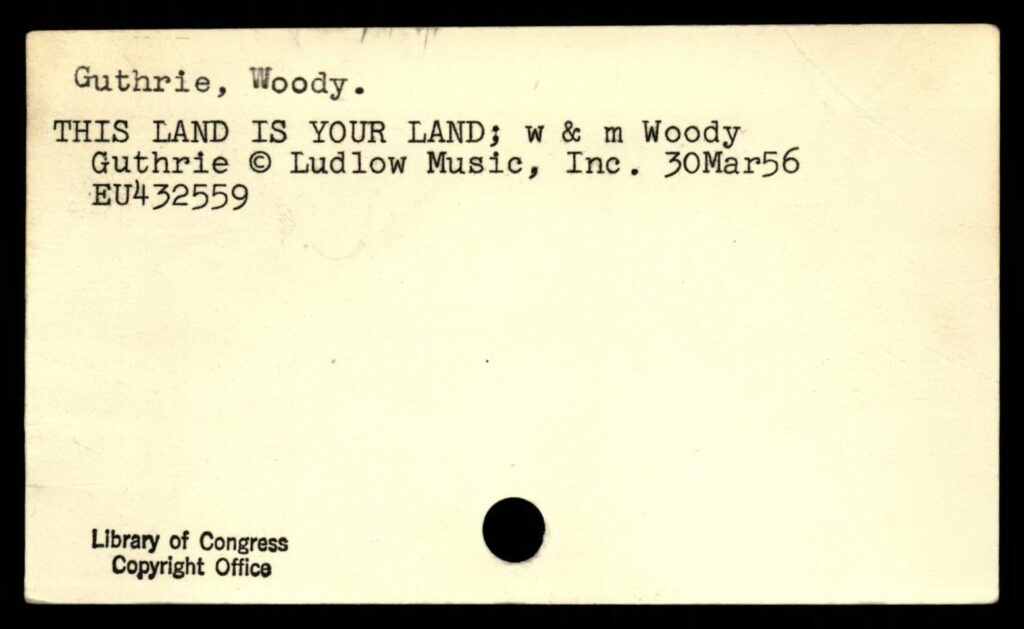

Yet, “This Land” was not officially registered with the Copyright Office until 1956. By this time, Guthrie was profoundly debilitated by Huntington’s Disease. Management of his affairs was handled by his second wife, Marjorie Mazia Guthrie, and her designees. It is possible that when they submitted the application for copyright registration they were unaware of the songbook’s existence. In the mid-1950s, “This Land” was just beginning to achieve the popular recognition it would eventually enjoy, and a hastily drawn songbook he had made a decade prior would likely not even register on their radar as they worked to untangle the myriad contracts and assignments of rights Guthrie had signed since he arrive in New York.[14]

The question of the copyright claim’s legitimacy hangs on a comparative evaluation of the 1945 manuscript and the 1956 registration. Records in the archives of the Woody Guthrie Center demonstrate that the successive entities who managed the copyright, including TRO, believed the 1956 registration to be valid.[15] Yet, when the copyright was challenged in 2004, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) discovered the 1945 manuscript and positioned it as evidence of “first publication.”[16] That case, like the one in 2016, eventually settled without ruling on the validity of the copyright claim, but the question of first publication will be important if suit is filed again in the future. TRO correctly filed for an extension of the 1956 registration in the twenty eighth year timeframe required at the time (i.e. pre-1976 Copyright Act). If the copyright clock legally began with the publication of the 1945 manuscript, however, the extension window was missed and the song would have fallen into the public domain twenty eight years later in 1973.

Conclusion

Ultimately, if a ruling is made, it will come down to a judge’s decision on whether the 1945 manuscript should count as first publication. When I began this research, I had hoped to produce a definitive recommendation similar to what Robert Brauneis was able to do with his work on “Happy Birthday.”[17] While I am not able to say definitively whether or not the copyright claim in “This Land” is valid, I do believe the case for its validity is stronger than many previous commentators have suggested.

It does not take a professional musicologist to note several differences in the sheet music from 1945 and 1956. They are in different keys and different time signatures. The melodies notated are both recognizable as “This Land,” but they have differences that even an untrained ear can easily distinguish. There are differences in the lyrics as well. For example, the 1945 manuscript has “Canadian Mountain” in place of the more familiar “Redwood Forest” in the first verse, and that difference is just one of many. Even the title on the 1945 manuscript is simply “This Land” rather than the full “This Land Is Your Land.” These discrepancies suggest a strong case that the manuscript accompanying the 1956 registration can reasonably be considered an updated arrangement or version deserving of its own unique copyright. If a judge were to rule the 1956 registration valid, then the current copyright claim would stand as legitimate.

The stakes of “This Land”’s copyright legitimacy are not insignificant. Nora Guthrie, Woody’s daughter and President of Woody Guthrie Publications, has stated explicitly why the claim is still asserted: “Our control of this song has nothing to do with financial gain. . . . It has to do with protecting it from Donald Trump, protecting it from the Ku Klux Klan, protecting it from all the evil forces out there.”[18] In my research, I did not find any scholarship that advocated for “This Land” to become public domain that also seriously addressed the ramifications of that outcome. The copyright claim may be disputed, but it is the only thing currently keeping the song from being appropriated into any number of commercial or political purposes that would have been anathema to Guthrie. It would be ideal, perhaps, if there were a mechanism other than copyright to restrict harmful use of “This Land,” but absent such a mechanism copyright is, in this case, the only thing helping to prevent appropriation and commodification.

References

[1] Most biographies of Guthrie have a section that covers the composition of “This Land Is Your Land.” See Robert Santelli, This Land Is Your Land: Woody Guthrie and the Journey of an American Folk Song (Philadelphia: Running Press, 2012) for an accurate yet accessible narrative. See John Shaw, “The Textual History of ‘This Land Is Your Land” in This Land That I Love: Irving Berlin, Woody Guthrie, and the Story of Two American Anthems (New York: PublicAffairs, 2013), 211-218 for a more detailed analysis.

[2] Jason Lee Guthrie, “This Copyright Kills Fascists: Debunking the Mythology Surrounding Woody Guthrie, ‘This Land is Your Land,’ and the Public Domain,” Information & Culture 58, no. 1 (2023): 17-38.

[3] Plaintiff’s Complaint, ECF No. 6, Saint-Amour et al v. The Richmond Organization, Inc. (TRO Inc.), June 15, 2016, (S.D.N.Y. 2016) (No. 16 Civ. 4464).

[4] Christine Mai-Duc, “All the ‘Happy Birthday’ song copyright claims are invalid, federal judge rules,” Los Angeles Times, September 22, 2015, https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-happy-birthday-song-lawsuit-decision-20150922-story.html.

[5] Niraj Chokshi, “Who Owns the Copyright to ‘This Land Is Your Land’? It May Be You and Me,” New York Times, June 17, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/18/business/media/this-guthrie-song-is-your-song-a-lawsuit-claims.html

[6] See, for example, Alonzo M. Zilch’s own Collection of Original Songs and Ballads (Songbook), April 1935, Item 87, Woody Guthrie Notebooks (Diaries), Woody Guthrie Center Archives, Tulsa, Oklahoma (hereafter WGC), Guthrie’s earliest known songbook, which included the quote: “At times I cannot decide on a tune to use with my words for a song. Woe is me! I am then forced to use some good old, family style tune that hath already gained a reputation as being liked by the people.”

[7] Ed Cray, Ramblin’ Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004), 165-166.

[8] https://www.rollingstone.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/This-Land-v1.jpg?w=1280

[9] Woody Guthrie, “This Land Is Your Land (Alternate Version),” c. mid-1940s, on Woody at 100: The Woody Guthrie Centennial Collection, Smithsonian Folkways, 2012.

[10] See Woody Guthrie, “This Land Is Your Land”, c. late-1940s, on This Land Is Your Land: The Asch Recordings, Vol. 1, Smithsonian Folkways, 1997; and Woody Guthrie, “This Land Is Your Land,” 1951, on This Land Is My Land: American Work Songs: Songs to Grow On, Vol. 3, Smithsonian Folkways Archival, 2007.

[11] Peter La Chapelle, I’d Fight the World: A Political History of Old-Time, Hillbilly, and Country Music (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2019), 165-166.

[12] “‘Ten Songs of Woody Guthrie’ 1945 Pamphlet,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, June 29, 2007, https://www.eff.org/document/ten-songs-woody-guthrie-1945-pamphlet.

[13] See, for example, Copyright Office to Woody Guthrie, September 22, 1937, Series 4, Box 6, Folder 3, Maxine Crissman “Woody and Lefty Lou” Radio Show Collection, WGC; and Copyright Office to Woody Guthrie, n.d., Series 4, Box 6, Folder 4, Maxine Crissman “Woody and Lefty Lou” Radio Show Collection, WGC.

[14] Joe Klein, Woody Guthrie: A Life, 2nd ed. (New York: Random House, 1999), 430-432.

[15] See, for example, Harold Leventhal to Woody Guthrie, August 27, 1956, Series 2, Box 2, Folder 13, Woody Guthrie’s Correspondence Collection, WGC; Harold Leventhal to Cisco Houston, November 25, 1958, Series 3, Box 1, Folder 10, Harold Leventhal Collection, WGC; Al Brackman to Harold Leventhal, January 13, 1959, Series 1, Box 1, Folder 16, Harold Leventhal Collection, WGC; Jay Mark to Harold Leventhal, December 7, 1959, Series 3, Box 1, Folder 8, Harold Leventhal Collection, WGC; Al Brackman to Harold Leventhal, December 22, 1959, Series 1, Box 1, Folder 16, Harold Leventhal Collection, WGC; and Howard S. Richmond to Harold Leventhal, December 28, 1959, Series 3, Box 1, Folder 8, Harold Leventhal Collection, WGC.

[16] Fred von Lohmann, “This Song Belongs to you and Me,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, August 24, 2004, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2004/08/song-belongs-you-and-me; and Parker Higgins, “This Song (Still) Belongs to You and Me,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, February 2, 2015, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2015/02/song-still-belongs-you-and-me.

[17] Robert Brauneis, “Copyright and the World’s Most Popular Song,” Journal of the Copyright Society of the U.S.A 56, no. 2–3 (Winter-Spring 2009): 335–426.

[18] Ben Sisario, “A Fight to Make ‘We Shall Overcome’ and ‘This Land is Your Land’ Copyright Free,” New York Times, July 12, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/13/business/media/happy-birthday-is-free-at-last-how-about-we-shall-overcome.html. For an interesting account of the relationship between Woody Guthrie and Donald Trump’s father Fred, see Will Kaufman, “Woody Guthrie, ‘Old Man Trump’ and a real estate empire’s racist foundations,” The Conversation, January 21, 2016, https://theconversation.com/woody-guthrie-old-man-trump-and-a-real-estate-empires-racist-foundations-53026. For a recent example of appropriation, see Daniel Desrochers, “Woody Guthrie’s family to Josh Hawley: Stop using his lyrics, ‘insurrectionist’,” The Kansas City Star, March 13, 2023, https://www.kansascity.com/news/politics-government/article272998185.html.

By Tabrez Ebrahim

By Tabrez Ebrahim