With Section 512 of the DMCA, Congress sought to “preserve[] strong incentives for service providers and copyright owners to cooperate to detect and deal with copyright infringements that take place in the digital networked environment.”[1] Given the symbiotic relationship between copyright owners and service providers, Congress meant to establish an online ecosystem where both would take on the benefits and burdens of policing copyright infringement. This shared-responsibility approach was codified in the Section 512 safe harbors. But rather than service providers and copyright owners working together to prevent online piracy, Section 512 has turned into a notice-and-takedown regime where copyright owners do most of the work. This is not what Congress intended, and the main culprit is how the courts have misinterpreted Section 512’s red flag knowledge standards.

With Section 512 of the DMCA, Congress sought to “preserve[] strong incentives for service providers and copyright owners to cooperate to detect and deal with copyright infringements that take place in the digital networked environment.”[1] Given the symbiotic relationship between copyright owners and service providers, Congress meant to establish an online ecosystem where both would take on the benefits and burdens of policing copyright infringement. This shared-responsibility approach was codified in the Section 512 safe harbors. But rather than service providers and copyright owners working together to prevent online piracy, Section 512 has turned into a notice-and-takedown regime where copyright owners do most of the work. This is not what Congress intended, and the main culprit is how the courts have misinterpreted Section 512’s red flag knowledge standards.

Several provisions in Section 512 demonstrate that Congress expected service providers to also play a role in preventing copyright infringement by doing some of the work in finding and removing infringing material. In order to benefit from the safe harbors, service providers must designate an agent to receive takedown notices, respond expeditiously to takedown notices, act upon representative lists, implement reasonable repeat infringer policies, and accommodate standard technical measures. But it’s also clear that service providers have the duty to remove infringing content even without input from copyright owners. As the Senate Report notes, “Section 512 does not require use of the notice and take-down procedure.”[2] And the knowledge provisions in Section 512 reflect this. Absent a takedown notice, service providers must, “upon obtaining . . . knowledge or awareness” of infringing material or activity, “act[] expeditiously to remove . . . the material” in order to maintain safe harbor protection.[3]

Under Section 512, there are two kinds of knowledge that trigger the removal obligation without input from the copyright owner—actual and red flag. For sites hosting user-uploaded content, actual knowledge is “knowledge that the material or an activity using the material on the system or network is infringing”[4] and red flag knowledge is “aware[ness] of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent.”[5] Thus, actual knowledge requires knowledge that specific material (“the material”) or activity using that specific material (“activity using the material”) is actually infringing (“is infringing”), while red flag knowledge requires only general awareness (“aware[ness] of facts or circumstances”) that activity appears to be infringing (“is apparent”). There are similar knowledge provisions for search engines.[6]

Importantly, actual knowledge refers to “the material,” and red flag knowledge does not. It instead refers to “infringing activity”—and it’s not the infringing activity, but infringing activity generally.[7] However, with both actual and red flag knowledge, the service provider is obligated to remove “the material.”[8] With actual knowledge, the service provider doesn’t have to go looking for “the material” since it already has actual, subjective knowledge of it. But what about with red flag knowledge where the service provider only knows of “infringing activity” generally? How does it know “the material” to take down? The answer is simple: Once the service provider is subjectively aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity would be objectively apparent[9]—that is, once it has red flag knowledge—it has to investigate and find “the material” to remove.[10]

The examples given in the legislative history, which relate to search engines, show that red flag knowledge puts the burden on the service provider. As the Senate Report notes, merely viewing “one or more well known photographs of a celebrity at a site devoted to that person” would not hoist the red flag since the images might be licensed or fair use.[11] However, sites that are “obviously infringing because they . . . use words such as ‘pirate,’ ‘bootleg,’ or slang terms . . . to make their illegal purpose obvious . . . from even a brief and casual viewing” do raise the red flag.[12] And a search engine “that views such a site and then establishes a link to it . . . must do so without the benefit of a safe harbor.”[13] Thus, Congress didn’t want search engines worrying about questionable infringements on a small scale, but it also didn’t want search engines to catalog sites that are clearly dedicated to piracy. And, most importantly, red flag knowledge kicks in once a service provider looks at something that is “obviously pirate”—even if it’s an entire website.[14]

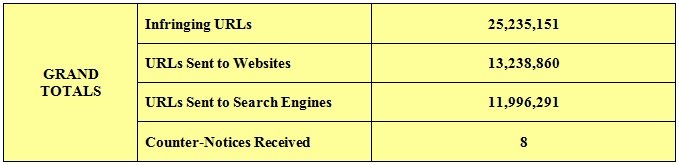

So how has Congress’s commonsensical plan worked out? Not very well. As of today, Google indexes nearly 1.5 million results from the infamous pirate site, The Pirate Bay.[15] Like the examples in the legislative history, The Pirate Bay has the word “pirate” in its title, and a brief viewing of the site reveals its obvious, infringing purpose. And it’s not like Google hasn’t been told that The Pirate Bay is dedicated to infringement—nor that it needs to be told. According to data from the Google Transparency Report,[16] the search engine has received requests to remove over 4 million URLs from thepiratebay.org domain alone. There are many other related domains, such as thepiratebay.se, that have received millions of requests as well. In fact, Google tells us that it has received requests to remove over 4 billion URLs from its search engine due to copyright infringement, with many domains receiving more than 10 million requests each.

So how is it that Google can index The Pirate Bay and not be worried about losing its safe harbor? The answer is that the courts have construed Section 512 in a way that contradicts the statutory text and Congress’s intent. They’ve all but read red flag knowledge out of Section 512 and placed the burden of policing infringement disproportionately on the copyright owner. And by narrowing the applicability of red flag knowledge, the courts have perversely incentivized service providers to do as little as possible to prevent infringements. Instead of looking into infringing activity of which they are subjectively aware, they are better off doing nothing lest they gain actual, specific knowledge that would remove their safe harbor protection.

A brief traverse through the case law, especially in the Second and Ninth Circuits, shows how the red flag knowledge train has been derailed. In Perfect 10 v. CCBill, the Ninth Circuit held that domains such as illegal.net and stolencelebritypics.com—the very sort of indicia mentioned in the legislative history—were not enough to raise the red flag.[17] According to the court, “describing photographs as ‘illegal’ or ‘stolen’ may be an attempt to increase their salacious appeal, rather than an admission that the photographs are actually illegal or stolen.”[18] While that’s certainly possible, it’s not likely. And it defies common sense. The Ninth Circuit concluded: “We do not place the burden of determining whether photographs are actually illegal on a service provider.”[19] But this misses the point, and it conflates red flag knowledge with actual knowledge.

The Second Circuit in Viacom v. YouTube held that the “difference between actual and red flag knowledge is . . . not between specific and generalized knowledge, but instead between a subjective and an objective standard.”[20] The court arrived there by focusing on the removal obligation, reasoning that “expeditious removal is possible only if the service provider knows with particularity which items to remove.”[21] And it rejected an “amorphous obligation” to investigate “in response to a generalized awareness of infringement.”[22] By limiting red flag knowledge to specific instances of infringement, the Second Circuit severely curtailed the obligations of service providers to police infringements on their systems. The entire point of red flag knowledge is to place a burden on the service provider to investigate the infringing activity further so that the specific material can be removed.[23]

The Ninth Circuit followed suit in UMG Recordings v. Shelter Capital, holding that red flag knowledge requires specificity.[24] The court reasoned that requiring “specific knowledge of particular infringing activity makes good sense” because it will “foster cooperation” between copyright owners and service providers “in dealing with infringement” online.[25] This “cooperation,” according to the Ninth Circuit, would come from takedown notices sent by copyright owners, who “know precisely what materials they own, and are thus better able to efficiently identify” infringing materials than service providers, “who cannot readily ascertain what material is copyrighted and what is not.”[26] Of course, this is not the shared-responsibility approach envisioned by Congress, and it conflates the red flag knowledge standards with the obligation to respond to takedown notices—separate provisions in Section 512.

Perhaps the most significant gutting of red flag knowledge can be found in the Second Circuit’s opinion in Capitol Records v. Vimeo.[27] The district court below had held that it was a question for the jury whether full-length music videos of current, famous songs that had been viewed by the service provider amounted to red flag knowledge.[28] But the Second Circuit disagreed that there was any jury question: “[T]he mere fact that a video contains all or substantially all of a piece of recognizable, or even famous, copyrighted music and was to some extent viewed . . . would be insufficient (without more) to sustain the copyright owner’s burden of showing red flag knowledge.”[29] That this gloss on red flag knowledge “reduces it to a very small category” was of “no significance,” the Second Circuit reasoned, since “the purpose of § 512(c) was to give service providers immunity, in exchange for augmenting the arsenal of copyright owners by creating the notice-and-takedown mechanism.”[30]

The Second Circuit thus held as a matter of law that there was no need for the factfinder to determine whether the material was so obviously infringing that it would raise the red flag. How is this a question of law and not fact? The court never explains. More importantly, this flies in the face of what Congress provided for with red flag knowledge, and it demotes Section 512 to being merely a notice-and-takedown regime where copyright owners are burdened with identifying infringements on URL-by-URL basis. Giving service providers a free pass when confronted with a red flag turns the Section 512 framework on its head. And it enables service providers to game the system and build business models on widespread, infringing content—even if they welcome it—so long as they respond to takedown notices. The end result is that an overwhelming amount of obvious infringements goes unchecked, and there’s essentially no cooperation between service providers and copyright owners as Congress intended.

[1] S. Rep. No. 105-190, at 40 (emphasis added); see also H.R. Rep. No. 105-551(II), at 49.

[2] Id. at 45; see also H.R. Rep. No. 105-551(II), at 54.

[3] 17 U.S.C. § 512(c)(1)(A)(iii); see also 17 U.S.C. § 512(d)(1)(C).

[4] Id. at § 512(c)(1)(A)(i) (emphasis added).

[5] Id. at § 512(c)(1)(A)(ii) (emphasis added).

[6] See id. at §§ 512(d)(1)(A)-(B).

[7] See 4-12B Nimmer on Copyright § 12B.04[A][1][b][ii] (“By contrast, to show that a ‘red flag’ disqualifies defendant from the safe harbor, the copyright owner must simply show that ‘infringing activity’ is apparent—pointedly, not ‘the infringing activity’ alleged in the complaint.” (emphasis in original)).

[8] 17 U.S.C. § 512(c)(1)(A)(iii)

[9] S. Rep. No. 105-190, at 44 (“The ‘red flag’ test has both a subjective and an objective element. In determining whether the service provider was aware of a ‘red flag,’ the subjective awareness of the service provider of the facts or circumstances in question must be determined. However, in deciding whether those facts or circumstances constitute a ‘red flag’–in other words, whether infringing activity would have been apparent to a reasonable person operating under the same or similar circumstances–an objective standard should be used.”); see also H.R. Rep. No. 105-551(II), at 53.

[10] Id at 48 (“Under this standard, a service provider would have no obligation to seek out copyright infringement, but it would not qualify for the safe harbor if it had turned a blind eye to ‘red flags’ of obvious infringement.”); see also H.R. Rep. No. 105-551(II), at 57.

[11] Id.; see also H.R. Rep. No. 105-551(II), at 57-58.

[12] Id.; see also H.R. Rep. No. 105-551(II), at 58.

[13] Id. at 48-49; see also H.R. Rep. No. 105-551(II), at 58.

[14] Id. at 49; see also H.R. Rep. No. 105-551(II), at 58.

[15] See The Pirate Bay, available at https://www.thepiratebay.org/.

[16] See Google Transparency Report, available at https://transparencyreport.google.com/.

[17] See Perfect 10, Inc. v. CCBill LLC, 488 F.3d 1102 (9th Cir. 2007).

[18] Id. at 1114.

[19] Id.

[20] Viacom Int’l, Inc. v. YouTube, Inc., 676 F.3d 19, 31 (2d Cir. 2012).

[21] Id. at 30.

[22] Id. at 30-31.

[23] See, e.g., H.R. Rep. No. 105-551(I), at 26 (“Once one becomes aware of such information, however, one may have an obligation to check further.”).

[24] UMG Recordings, Inc. v. Shelter Capital Partners LLC, 718 F.3d 1006 (9th Cir. 2013).

[25] Id. at 1021-22.

[26] Id. at 1022.

[27] Capitol Records, LLC v. Vimeo, LLC, 826 F.3d 78 (2d Cir. 2016).

[28] Capitol Records, LLC v. Vimeo, LLC, 972 F. Supp. 2d 537, 549 (S.D.N.Y. 2013) (“[B]ased on the type of music the videos used here—songs by well-known artists, whose names were prominently displayed—and the placement of the songs within the video (played in virtually unaltered form for the entirety of the video), a jury could find that Defendants had ‘red flag’ knowledge of the infringing nature of the videos.”).

[29] Capitol Records, 826 F.3d at 94 (emphasis in original).

[30] Id. at 97.

I presented this at the Fordham IP Conference on April 25, 2019. My oral presentation is here, and the accompanying slides are here.

By Liz Velander

By Liz Velander By Yumi Oda

By Yumi Oda With Section 512 of the DMCA, Congress sought to “preserve[] strong incentives for service providers and copyright owners to cooperate to detect and deal with copyright infringements that take place in the digital networked environment.”

With Section 512 of the DMCA, Congress sought to “preserve[] strong incentives for service providers and copyright owners to cooperate to detect and deal with copyright infringements that take place in the digital networked environment.” One year ago, domain name registry Donuts, Inc. and the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) entered into an agreement termed the Trusted Notifier Program in a joint effort to combat piracy. The voluntary initiative “introduced a new way to work towards mitigation of clear and pervasive cases of copyright infringement,” and according to

One year ago, domain name registry Donuts, Inc. and the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) entered into an agreement termed the Trusted Notifier Program in a joint effort to combat piracy. The voluntary initiative “introduced a new way to work towards mitigation of clear and pervasive cases of copyright infringement,” and according to  In a

In a  On December 14th, a group of librarians sent a

On December 14th, a group of librarians sent a  Last week, the European Court of Justice—the judicial authority of the European Union—issued an anticipated

Last week, the European Court of Justice—the judicial authority of the European Union—issued an anticipated  In a recent

In a recent