The following post comes from CPIP Programs and Research Associate Terrica Carrington, a rising 3L at George Mason University School of Law, and Devlin Hartline, Assistant Director at CPIP. They review a paper from CPIP’s 2014 Fall Conference, Common Ground: How Intellectual Property Unites Creators and Innovators, that was recently published in the George Mason Law Review.

By Terrica Carrington & Devlin Hartline

In his paper, Patent Licensing and Secondary Markets in the Nineteenth Century, CPIP Senior Scholar Adam Mossoff gives important historical context to the ongoing debate over patent licensing firms. He explains that some of the biggest misconceptions about such firms are that the patent licensing business model and the secondary market for patents are relatively new phenomena. On the contrary, Mossoff shows that “famous nineteenth-century American inventors,” such as Charles Goodyear, Elias Howe, and Thomas Edison, “wholeheartedly embraced patent licensing to commercialize their inventions.” Moreover, he demonstrates that there was “a vibrant secondary market” where patents were bought and sold with regularity.

Like many inventors, Mossoff explains, it was curiosity—rather than market success—that drove Charles Goodyear to create. Despite having invented the process for vulcanized rubber, Goodyear “never manufactured or sold rubber products.” While he enjoyed finding new uses for the material, commercialization was not his niche. Instead, Goodyear “transferred his rights in his patented innovation to other individuals and firms” so that they could capitalize on his inventions. “As the archetypal obsessive inventor,” notes Mossoff, “Goodyear was not interested in manufacturing or selling his patented innovations.” In fact, his assignees and licensees “filed hundreds of lawsuits in the nineteenth century,” demonstrating that “patent licensing companies are nothing new in America’s innovation economy.”

Mossoff next looks at Elias Howe, best known for his invention of the sewing machine lockstitch in 1843, who “licensed his patented innovation for most of his life.” Howe was also famous for “suing commercial firms and individuals for patent infringement” and then entering into royalty agreements with them. It was Howe’s troubles with “noncompliant infringers” that “precipitated the first ‘patent war’ in the American patent system—called, at the time, the Sewing Machine War.” Howe engaged in “practices that are alleged to be relatively novel today,” such as “third-party litigation financing,” and he even joined “the first patent pool formed in American history,” known as “the Sewing Machine Combination of 1856.”

Finally, Mossoff discusses Thomas Edison, whom many consider to be “an early exemplar of the patent licensing business model.” Edison sold and licensed his patents, especially early on, so that he could fund his research and development. However, Edison is a “mixed historical example” since “he manufactured and sold some of his patented innovation to consumers, such as the electric light bulb and the phonograph.” Moreover, despite his “path-breaking inventions,” the marketplace was often dominated by his competitors. Mossoff notes that Edison was a better inventor than businessman: “At the end of the day, Edison should have stuck to the patent licensing business model that brought him his justly earned fame as a young innovator at Menlo Park.”

While some might call these inventors anomalies, Mossoff reveals that they were in good company with others who utilized the patent licensing business model to serve “one of the key policy functions of the patent system by commercializing patented innovation in the United States.” These include “William Woodworth (planing machine), Thomas Blanchard (lathe), and Obed Hussey and Cyrus McCormick (mechanical reaper)” and many others who “sold or licensed their patent rights in addition to engaging in manufacturing and other commercial activities.” This licensing business model continues to be used today by innovative firms such as Bell Labs, IBM, Apple, and Nokia.

Mossoff next rebuts the “oft-repeated claim” made by many law professors that “large-scale selling and licensing of patents in a secondary market is a recent phenomenon.” This claim is as “profoundly mistaken as the related assertion that the patent licensing business model is novel.” Mossoff notes that during the Sewing Machine War of the Antebellum Era, “the various patents obtained by different inventors on different components of the sewing machine were purchased or exchanged between a variety of individuals and firms.” As early as the 1840s, individuals acquired patents in the secondary market and used them to sue infringers.

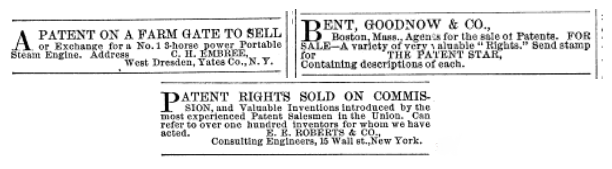

In fact, Mossoff points out that it was not uncommon to see newspaper ads offering patents for sale in the nineteenth century:

The classified ads in Scientific American provide a window into this vibrant and widespread secondary market. In an 1869 issue of Scientific American, among ads touting the value to purchasers of “Woodbury’s Patent Planing and Matching and Moulding Machines” and ads declaring “AGENTS WANTED—To sell H.V. Van Etten’s Patent Device for Catching and Holding Domestic Animals,” one finds ads offering patents and rights in patents for sale:

Such ads were ubiquitous in the nineteenth century, says Mossoff, and they “belie any assertions about the absence of such historical secondary markets by commentators today.” Similarly, Mossoff points to research showing the “fundamental and significant role” performed by intermediaries known as “patent agents,” the “predecessors of today’s patent aggregators.” These patent agents invested in a wide range of products and industries—a remarkable feat given the “constraints of primitive, nineteenth-century corporate law and the limited financial capabilities of market actors at that time.”

In his brief yet insightful account of the history of patent licensing firms, Mossoff refutes the modern misconception that “the patent licensing business model and secondary markets in patents are novel practices today.” It’s important to set the record straight, especially as many in modern patent policy debates rely on erroneous historical accounts to make negative inferences. The evidence from the nineteenth century isn’t that surprising since it reflects “the basic economic principle of the division of labor that Adam Smith famously recognized as essential to a successful free market and flourishing economy.” Casting “aspersions on this basic economic principle,” Mossoff concludes, “strikes at the very core of what it means to secure property rights in innovation through the patent system.”