I am looking forward to hosting a keynote conversation with Grammy-winning composer, performer, songwriter, best-selling author, and essayist Rosanne Cash this week at CPIP’s The Evolving Music Ecosystem conference. One part of Rosanne Cash’s “music ecosystem” is the Artist Rights Alliance (ARA), where she serves as a member of the board. Preparing for that conversation, I am thinking a lot about the importance of artists’ agency. Over the summer, the ARA “rebooted,” relaunching itself with a powerhouse music council of artists and experts. The ARA is “an alliance of working musicians, performers, and songwriters fighting for a healthy creative economy and fair treatment for all creators in the digital world. [They] work to defend and protect artists, guided by [their] Artists’ Bill of Rights, which outlines fundamental principles for today’s music economy.”

I am looking forward to hosting a keynote conversation with Grammy-winning composer, performer, songwriter, best-selling author, and essayist Rosanne Cash this week at CPIP’s The Evolving Music Ecosystem conference. One part of Rosanne Cash’s “music ecosystem” is the Artist Rights Alliance (ARA), where she serves as a member of the board. Preparing for that conversation, I am thinking a lot about the importance of artists’ agency. Over the summer, the ARA “rebooted,” relaunching itself with a powerhouse music council of artists and experts. The ARA is “an alliance of working musicians, performers, and songwriters fighting for a healthy creative economy and fair treatment for all creators in the digital world. [They] work to defend and protect artists, guided by [their] Artists’ Bill of Rights, which outlines fundamental principles for today’s music economy.”

Those principles:

The Right to Economic and Artistic Freedom

The Right to Attribution and Acknowledgment

The Right to a Music Community

The Right to Competitive Platforms

The Right to Information and Platform Transparency

The Right to Political Participation

All share one core attribute—an artist’s agency—over their work, their livelihood, their community, themselves. That the ARA found it necessary to relaunch this summer is not surprising. The triple threat of a pandemic decimating artists’ livelihoods, the surging power of technology platforms, and the challenges of ensuring one’s work is not distorted by others or used to send disagreeable political messages has heightened awareness among artists about the issues for which ARA stands.

Several notable lawsuits have also brought these issues to the forefront this summer that may shape the nature of artists’ agency over their work for years to come. Here are some thoughts about why they are significant and some issues you may not have noticed.

Hachette Book Group et al. v. Internet Archive

On June 1, 2020, four of the world’s preeminent publishing houses sued Internet Archive (IA) for willful mass copyright infringement. The IA styles itself an online library, open to anyone to borrow books, music, and other works. It scans millions of copyrighted as well as public domain works and makes them available to “borrowers” for free. It had previously operated under an already controversial policy of “controlled digital lending” (more on that below), but in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, dropped even these minimal restrictions on its distribution of works. As the Authors Guild put it in an open letter to the IA:

In their complaint, the publishers argue that IA’s assertion that it should not be liable for infringement is based on “an invented theory called ‘Controlled Digital Lending’ (‘CDL’)—the rules of which have been concocted from whole cloth and continue to get worse.” As the complaint sets forth:

The publishers’ lawsuit is important because it is the first “live” judicial challenge to the legal theory of “controlled digital lending”—a legal theory which was announced by certain academics and internet advocates in 2018. They argue that it should be fair use for libraries to scan or obtain scans of physical books they own and lend them electronically, provided certain restrictions are applied, such as limitations that attempt to emulate the limitations of lending in the physical world (e.g., limits on lending periods and on numbers of copies that can be loaned at a given time).

I refer to this as the first “live” judicial challenge because, while it is the first time CDL has been challenged in the courts, the supporters of CDL sought and failed to receive the blessing of the Second Circuit for IA’s original Open Library service when that court was reviewing the decision in Capitol Records v ReDigi. Unsurprisingly, the court declined to do so. In an opinion written by Judge Leval, the Second Circuit rejected ReDigi’s and its amici’s fair use argument because market harm would be likely since the sales of ReDigi’s digital files would compete directly with those of Capitol Records. Because “used” digital files do not deteriorate like used physical media, there would be no reason for customers to buy new licenses from Capitol Records if they could obtain the files from ReDigi at a lower price.

One imagines that the impact of free CDL on e-book sales would only be worse—first, because it is free, rather than merely a reduced price for “used” files, and second, because it would be usurping a valuable market authors and publishers have continued to actively develop and license for several years since the ReDigi decision. This includes licensing to libraries for free lending via services like OverDrive. It is likewise significant that the “Emergency Library” at issue in the publishers’ case against IA is far less restricted than the version of IA’s “Open Library” the amici sought and failed to have blessed by the Second Circuit in ReDigi.

Maria Schneider et. al. v. YouTube

Another case to watch is the class action lawsuit filed by composer and jazz performer Maria Schneider against YouTube and its parent companies Google and Alphabet in July. The lawsuit alleges that “YouTube has facilitated and induced [a] hotbed of copyright infringement [on its website] through its development and implementation of a copyright enforcement system that protects only the most powerful copyright owners such as major studios and record labels.” Because members of the class are denied access to the copyright management tool YouTube offers its corporate partners—Content ID—the lawsuit alleges that rather than preventing repeat infringements of works, the tool “actually insulates the vast majority of known and repeated copyright infringers from YouTube’s repeat infringer policy, thereby encouraging its users’ continuing upload of infringing content.”

This is all part of a deliberate strategy, according to the complaint:

Maria Schneider argues many of the same things she and other artist advocates have asserted before Congress, the U.S. Copyright Office, and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in hearings and roundtable proceedings exploring the provisions of Section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA):

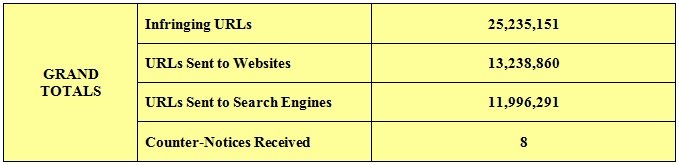

They must then send notices identifying infringements URL by URL, filling out cumbersome webforms, often laden with advertising, struggle with captcha codes, and contend with requests for additional information or challenges from employees reviewing the requests.

While many artists have neither the pocketbook nor the backbone to stand up to an adversary like YouTube in federal court, this lawsuit seems particularly well-timed given that the ongoing focus on Section 512 in multiple government venues over the past decade has developed a solid record articulating the scope and the magnitude of the problem, as well as that the complaints against YouTube and other web platforms by individual artists seem to be almost universally shared.

Regardless of Maria Schneider’s lawsuit, the Senate and the U.S. Copyright Office are not done considering the issue. The Copyright Office released its much-anticipated Section 512 Report earlier this May and engaged in a subsequent exchange of letters with Senators Thom Tillis and Patrick Leahy regarding additional statutory clarifications that the Senate might consider and other approaches that could improve the operation of the DMCA without legislative amendment. Among the issues addressed in that letter is a request from the Senators to the Copyright Office to conduct stakeholder meetings to identify and adopt standard technical measures (STMs) as was anticipated in Section 512(i) of the DMCA. It is notable that Maria Schneider has herself been an active participant in the Copyright Office’s Section 512 proceedings, and in February of 2017, she submitted comments to the Copyright Office urging that Content ID be recognized as a STM under the DMCA and that all creators be granted access to it in order to be able to more efficiently police YouTube’s platform. The Copyright Office did not take up her suggestion.

In answer to the Tillis/Leahy request, on June 29, 2020, the Copyright Office responded in part that it will convene virtual meetings in late summer/early fall “focused on identifying any potential obstacles to the identification of potential STMs, as well as the requirements that must be met in order to adopt and implement an STM,” and to “begin identifying the kinds of technologies that may meet the statutory definition. Once the bounds of potential qualifying technologies have been identified, the Office would then convene further discussion to evaluate whether individual technologies meet the other requirements of section 512(i), including discussions to learn more about the terms upon which the technologies are offered in the marketplace.”

To date, hypothetical discussions (as well as lawsuits and licensing) have focused on digital fingerprinting technologies. Such technologies are designed to identify content by taking a “fingerprint” of a file that is being or has been uploaded to a platform and matching it to a database of sample content submitted by copyright owners. Regardless of the technology identified as an STM, the challenge may come not from choosing the technology, but rather in applying it. What one copyright owner is willing to tolerate in the name of marketing and fan word of mouth, another will not be. What a technology platform may set the technology to overlook, a filmmaker on the eve of a festival premiere will consider a “match.” Hence the importance of artists’ agency. Or as the ARA would have it: the right to competitive platforms and the right to information and platform transparency. Unless artists are informed about the STMs platforms apply and how they apply them, and unless they have the ability to keep their work from platforms that don’t meet their requirements, identifying an STM on its own won’t make much of a difference. Without artists’ agency and the right to control what happens to their creative output, we may just have the digital fingerprint version of the notice-and-takedown “whack-a-mole” game.[1]

Neil Young v. Donald J. Trump for President

Musicians have perpetually battled with political campaigns over the unauthorized use of their music at rallies and other campaign events. Given the particularly heated nature of this year’s presidential contest, it is perhaps not surprising that Neil Young has sued the Trump campaign for copyright infringement for publicly performing his musical works Rockin’ in the Free World and Devil’s Sidewalk at numerous campaign rallies and events, including one in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The complaint alleges: “The Campaign has willfully ignored Plaintiff’s telling it not to play the Songs and willfully proceeded to play the Songs despite its lack of a license and despite its knowledge that a license is required to do so.”

Neil Young is not the only musician battling the Trump campaign. Leonard Cohen’s estate is considering whether to file suit for the campaign’s use of Halleluiah during the last night of the Republican National Convention, and the Rolling Stones are working with ASCAP and BMI to persuade the Trump campaign to stop playing You Can’t Always Get What You Want at rallies. Campaigns typically assert that they are permitted to play any songs included in the Performing Rights Organizations’ political entities licenses, from which artists may seek to exclude their works if they object to use at political rallies. The allegations by Neil Young, the Cohen estate, and the Stones seem to be that the particular uses by the Trump campaign have gone beyond what a venue license for a political gathering envisions and that the campaign is instead using the songs to either distort their meaning or suggest an endorsement by the artist.

As the members of the Artist Rights Alliance wrote to all of the Republican and Democratic National Campaign Committees this July: “Like all other citizens, artists have the fundamental right to control their work and make free choices regarding their political expression and participation. Using their work for political purposes without their consent fundamentally breaches those rights—an invasion of the most hallowed, even sacred personal interests.”

These lawsuits are interesting because, until now, due to a combination of the veneer of protection offered by the venue licenses, and the time constraints imposed by campaign season, the only viable mechanism for discouraging unwanted uses of an artist’s work by a campaign has been public shaming via social media or statements by the artist publicly disowning and rejecting the candidate. Consequently, neither the moral rights or right of publicity-like qualities of the complaints nor the availability of damages for the infringing use have been explored. Since the Trump campaign is unlikely to settle a lawsuit, this case may define the boundaries of political entities licensed uses or add a new tool to musicians’ arsenals in ensuring they are not unwillingly conscripted into the service of a campaign they do not support.

RIP Matt Herron[2]

A civil rights era photographer I admired and came to know when I was CEO of the Copyright Alliance—Matt Herron—recently passed. Matt was inspiring on many levels. He described himself as an “activist with a camera,” and he covered some of the most meaningful moments in the effort to gain voting rights for Black people in the 1960s—including the Selma to Montgomery march.

“I photograph things I believe in. I try to photograph the things that are important in my life,” said Herron during a panel I moderated in 2011. He felt so strongly about what he saw happening in the 1960s south that he picked up his family and moved from Philadelphia to Mississippi because he thought they could be more relevant there. In doing so, through his photographs, he gave countless generations a front row seat to history. He described the five days he spent documenting the march from Selma to Montgomery:

Matt Herron lived by the copyright of his photographs and used them to further education about the social causes he covered. Besides the Selma march, he shot whaling protests by Greenpeace and the AIDS quilt. He explained that copyright laws help him keep collections of his images together and allow him to present them for the benefit of the causes covered:

Matt Herron’s lifetime of work demonstrates in a way that is perhaps clearer this summer than any in recent memory why ensuring that artists are guaranteed agency over their creative output—whether they be photographers chronicling our history, musicians expressing our yearning, or authors giving words to our conscience—is crucial to democracy.

[1] Although it is approximately a decade old, this article, The (Im)possibility of “Standard Technical Measures” for UGC Websites, written by then student, now partner at Wilson Sonsini, Lauren Gallo, is the most thorough, balanced, and articulate examination of the issues the USCO is undertaking to date. Gallo notes that already in 2011 when her note was published, rights owners and UGC service providers were deploying fingerprinting technology to protect copyrighted works on the internet and operate repeat infringer policies. She writes: “In light of the widespread use of this successful technology and Congress’ mandate that ‘standard technical measures’ be developed ‘expeditiously,’ individual or infrequent holdouts should not obstruct the consensus necessary to define the term. . . . [F]ingerprinting technology should qualify as ‘standard technical measures’ under section 512(i), so that right holders and service providers may be on notice of their statutory obligations and may continue to develop ‘best practice’ applications for that technology.”

Ms. Gallo’s current practice focuses on novel legal questions online, involving among other issues, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, and she has represented Google and YouTube in cases challenging their decisions regarding whether or not to remove or limit access to online content.

[2] Portions of this section appeared as a blog post in June of 2011 on the Copyright Alliance website, when I was CEO of that organization.

As formats change and advances in technology continue to transform the way we listen to music, new methods of pirating content are never far behind. What started with the analog dubbing and bootlegging of cassettes forty years ago evolved with the digital age into CD burning and MP3 sharing, eventually leading to a chaotic illegal downloading landscape at the turn of the century that would force the music industry to develop novel anti-piracy efforts and distribution models. Digital streaming services have since taken over as the preferred way to consume music, boasting over

As formats change and advances in technology continue to transform the way we listen to music, new methods of pirating content are never far behind. What started with the analog dubbing and bootlegging of cassettes forty years ago evolved with the digital age into CD burning and MP3 sharing, eventually leading to a chaotic illegal downloading landscape at the turn of the century that would force the music industry to develop novel anti-piracy efforts and distribution models. Digital streaming services have since taken over as the preferred way to consume music, boasting over  On December 14th, a group of librarians sent a

On December 14th, a group of librarians sent a  In 2013, CPIP published a policy brief by Professor Bruce Boyden exposing the DMCA notice and takedown system as outdated and in need of reform.

In 2013, CPIP published a policy brief by Professor Bruce Boyden exposing the DMCA notice and takedown system as outdated and in need of reform.