This past Friday, the Ninth Circuit handed down its opinion in Dr. Seuss v. ComicMix, a closely watched transformative fair use case. The decision marks an important milestone in the development of the fair use doctrine, especially as applied to mash-ups—where two or more preexisting works are blended together to create a new work. However, the court’s careful explanation of what constitutes transformativeness is not limited to mash-ups, and it will surely be influential for years to come. In this post, I’ll look at the various views expressed by the parties, amici, and courts as to what it means for a use to be transformative, and I’ll explain how the Ninth Circuit’s new guidance on transformativeness reins in some of the overly broad positions that have been urged. This decision should be welcome news for those who worry that a copyright owner’s right to make derivative works has been excessively narrowed by ever-expanding notions of transformative use.

This past Friday, the Ninth Circuit handed down its opinion in Dr. Seuss v. ComicMix, a closely watched transformative fair use case. The decision marks an important milestone in the development of the fair use doctrine, especially as applied to mash-ups—where two or more preexisting works are blended together to create a new work. However, the court’s careful explanation of what constitutes transformativeness is not limited to mash-ups, and it will surely be influential for years to come. In this post, I’ll look at the various views expressed by the parties, amici, and courts as to what it means for a use to be transformative, and I’ll explain how the Ninth Circuit’s new guidance on transformativeness reins in some of the overly broad positions that have been urged. This decision should be welcome news for those who worry that a copyright owner’s right to make derivative works has been excessively narrowed by ever-expanding notions of transformative use.

In Dr. Seuss v. ComicMix, the plaintiff, Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. (Seuss), was the assignee of the copyrights to the works by Theodor S. Geisel, the late author who wrote under the pseudonym “Dr. Seuss.” Seuss sued the defendants, ComicMix LLC and three individuals (collectively, ComicMix), for copyright infringement over, inter alia, ComicMix’s mash-up of Seuss’ iconic Oh, the Places You’ll Go! (Go!) with a Star Trek theme, entitled Oh, the Places You’ll Boldly Go! (Boldly). The Boldly mash-up featured slavish copies of the images and overall look and feel of Go!, but with the Seussian characters replaced with the crew of the Enterprise from Star Trek and the text and imagery reinterpreted for Trekkies.

ComicMix admitted that it copied Go! to create Boldly, and the issue on appeal was whether its use was fair. The district court held that it was fair use, finding in particular that ComicMix’s mash-up was “highly transformative.” After the decision was appealed to the Ninth Circuit, there were amicus briefs filed for both sides. Some argued that Boldly was transformative, and others argued that it was not. In the opinion for the unanimous Ninth Circuit panel by Judge McKeown, the court held that Boldly wasn’t transformative at all. This decision gives us what is perhaps the clearest explanation of what it means to be a transformative use to date by an appellate court. And the fact that it comes from the Ninth Circuit—the “Hollywood Circuit” as Judge Kozinski once called it—makes it all the more interesting and important.

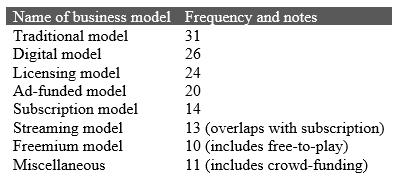

The issue of transformativeness is primarily analyzed under the first fair use factor, i.e., the purpose and character of the use, but it also weighs heavily on the other three factors. If the use is transformative, courts often ignore the creativeness of the original work, give the copyist more leeway when assessing the amount and substantiality of the use, and overlook the copyist’s effect on the potential market for the original work. As some have observed, in a transformative use case, the fair use analysis tends to collapse into a single factor: Is the use transformative? Indeed, Jiarui Liu published a study last year showing that “transformative use appears to be nearly sufficient for a finding of fair use.” Once the dispositive decisions included in the study found transformative use, they eventually held that there was fair use 94% of the time.

District Court Finds Boldly Is “Highly Transformative”

In the district court, the parties filed cross-motions for summary judgment, with ComicMix claiming fair use. The court had assessed fair use earlier in the litigation when denying ComicMix’s motion to dismiss. There, the court rejected ComicMix’s contention that Boldly was a parody, reasoning that it did not comment on or criticize the original work. Parodies juxtapose the original work for comedic effect, and the necessity of referencing the original justifies the copying. However, the court found that there was no such juxtaposition here, instead noting that Boldly merely used the “illustration style and story format as a means of conveying particular adventures and tropes from the Star Trek canon.” Nevertheless, the court found that Boldly was “no doubt transformative” since it “combine[d] into a completely unique work the two disparate worlds of Dr. Seuss and Star Trek.” Even though many elements were copied, the court reasoned that Go! had been “repurposed” because ComicMix added “original writing and illustrations” that transformed its Seussian pages into “Star-Trek-centric ones.”

The district court ultimately denied the motion to dismiss as it had to take Seuss’ allegations of market harm in the complaint as true and there was no evidence to the contrary in the record. Lacking evidence of market harm, the court found a “near-perfect balancing of the factors” and held that ComicMix’s “fair use defense currently fails as a matter of law.” However, once the court turned to the summary judgment motions, it had a developed record from which to work. On market harm, the court placed the burden on Seuss—despite fair use being an affirmative defense—and found that it failed to demonstrate likely harm to Go! or its licensed derivatives. On the issue of transformativeness, the court adopted and then expanded on its reasoning when addressing the motion to dismiss.

Suess had asked the district court to reassess its fair use analysis given the intervening Federal Circuit decision in Oracle v. Google. In that case, it was not fair use when Google copied computer code verbatim and then added its own code. The court here distinguished Oracle, reasoning that ComicMix did not copy the text or illustrations of Go! verbatim. While ComicMix “certainly borrowed from Go!—at times liberally—the elements borrowed were always adapted or transformed,” and that made Boldly “highly transformative.” Furthermore, the court found that Go! and Boldly served different purposes, with the former aimed at graduates and the latter tailored towards Trekkies. And to Seuss’ argument that Boldly was a derivative work, the court responded that derivative works can be transformative and constitute fair use.

Strangely, when addressing the motion to dismiss and the summary judgment motions, the district court failed to cite the holding of Dr. Seuss v. Penguin Books—even though that binding precedent involved the same plaintiff making similar arguments about a similar mash-up (there, Dr. Seuss and the O.J. Simpson murder trial). In Penguin Books, the Ninth Circuit held that the accused mash-up, The Cat NOT in the Hat! A Parody by Dr. Juice, was neither parody nor fair use. Rather than ridiculing the Seussian style itself, the court held that it merely copied that style “to get attention” or perhaps “to avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh”—as the Supreme Court put it in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose. Indeed, because the mash-up failed to conjure up the substance of the original work by focusing readers instead to the O.J. Simpson murder trial, the court held that there was “no effort to create a transformative work with ‘new expression, meaning, or message’” as required by Campbell.

Amicus Briefs Offer Differing Views on Transformativeness

Once the case was appealed to the Ninth Circuit, amicus briefs were filed on both sides addressing the transformativeness issue. Some argued that Boldly epitomized transformative fair use, and others argued that it was the antithesis. It is difficult to exaggerate the doctrinal gulf between the views of these amici.

The Motion Picture Association (MPA) amicus brief, by Jacqueline Charlesworth, argued that ComicMix’s use was not transformative since it failed to comment on or add new meaning to Go! and instead merely used it as a vehicle to achieve the same purpose—entertaining and inspiring readers. Moreover, ComicMix admitted that it could have used a different book on which to base its mash-up, thus defeating any claim of necessity. The MPA brief explained that Boldly was indeed a derivative work (the district court had expressively reserved the point) as defined by the Copyright Act since it transformed or adapted a preexisting work. The district court had dismissed Suess’ argument that Boldly was a derivative work by pointing out that it transformed and adapted Go!, but the MPA brief called this “troubling logic” since it conflated derivativeness with transformativeness and presumably would make every derivative work a transformative fair use.

Peter Menell filed an amicus brief, joined by Shyam Balganesh and David Nimmer, taking issue with the district court’s “categorical determination” that mash-ups generally are “highly transformative” as it would “undermine[] the Copyright Act’s right to prepare derivative works.” The Menell brief argued that Boldly “might well strike a lay observer as clever, engaging, and even transformative in a common parlance sense of the term,” but this misunderstands the transformativeness inquiry, which turns on whether it “serves a different privileged purpose” such that it survives the “justificatory gauntlet.” The question was whether Boldly “merely supersede[d] the objects of the original” or instead used the copied material “in a different manner or for a different purpose.” Here, the Menell brief concluded, Boldly drew on Go!’s popularity to follow its same general entertaining purpose while adding little “new insight and understanding.”

Sesame Workshop filed an amicus brief by Dean Marks distinguishing transformativeness for derivative works from transformative use under the first fair use factor and arguing that the district court conflated the two. The Sesame brief explained that Boldly was only transformative in the fair use sense if it, per Campbell, added “something new, with a further purpose or different character” as “commentary” and provided “social benefit, by shedding light on an earlier work.” While Boldly did add new material, it did not add “any new meaning or message” or “provide any new insight or commentary on Go!.” It instead delivered “the exact same inspirational message” to appeal to Seuss’ “existing market.” The danger of the district court’s logic, the Sesame brief concluded, is that it “could stand for the proposition that all mash-ups constitute fair use, a holding that would greatly diminish the derivative work right.”

An amicus brief by Erik Stallman on behalf of a group of IP professors, including Mark Lemley, Jessica Litman, Lydia Loren, Pam Samuelson, and Rebecca Tushnet, took a broad view of transformative fair use, arguing that the district court properly did not require Boldly to criticize, comment on, or parody Go! itself. It also claimed that fair use is not an affirmative defense such that the district court properly put the burden on Seuss to show market harm. The crux of the IP professor brief was that, even though on a high level of abstraction both works had the same entertainment purpose, there were nonetheless “differences in expressive meaning or message” that made Boldly transformative. As there were such differences at a lower level of abstraction—e.g., Go! had a “hyper-individualistic character” while Boldly focused on “institutional structures that promote discovery through” combined “efforts”—the IP professor brief concluded that it was transformative in the fair use sense.

Finally, an amicus brief by Mason Kortz on behalf of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), Organization for Transformative Works, Public Knowledge, and others concluded that “Boldly is a significantly transformative work” that “recasts, recontextualizes, and adds new expression or meaning to Go! in order to create a new, significant work of creative expression.” The EFF brief argued that uses can be transformative even if “they fail to comment on or parody the original” so long as they have different “expressive content and message.” Here, Boldly was transformative because it “adapt[ed] the stylistic, visual, and rhyming elements from Go! to create new expression” and added “new meanings that speak with particularity to the themes of Star Trek beloved by its community of fans.”

Ninth Circuit Holds that Boldly Is Not Transformative

Turning back to the parties, Seuss argued on appeal that ComicMix’s “use was exploitative and intended to grab the attention of potential buyers, not transformative,” since it added no “new purpose or meaning.” ComicMix answered that its use was “highly transformative,” with a “radically distinct purpose and effect,” that crafted “new meanings from the interplay between Star Trek’s and Seuss’s creative worlds.” Judge McKeown, writing for the unanimous Ninth Circuit panel, sided completely with Seuss: While the “fair use analysis can be elusive,” if not metaphysical, “[n]ot so with this case.” The court held that “Boldly is not transformative” and that all of the fair use “factors decisively weigh against ComicMix.”

Quoting Campbell, the court started with the premise that a transformative work “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message,” and a work that “merely supersedes the objects of the original creation” is not transformative. It also noted Campbell’s explanation that commentary with “no critical bearing on the substance or style of the original” and which is used “to get attention or to avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh” has less—if any—claim to fair use. The court then cited to its previous holding in Dr. Seuss v. Penguin Books (mentioned above as having been ignored by the district court below despite the glaring similarities) that the mash-up at issue there merely copied the Seussian style without critiquing it. The court there held that the defendant was only trying “to get attention,” and the court here found that the same result holds true. ComicMix’s “post-hoc characterization” that it was “criticizing the theme of banal narcissism of Go!” or “mocking the purported self-importance of its characters falls flat.”

The court then turned to ComicMix’s argument that, even if Boldly was not a parody or a critique, it was nonetheless transformative since it substituted Seussian characters and elements with Star Trek themes. The court rejected this framing as foreclosed by Penguin Books, noting that it “leverage[s] Dr. Seuss’s characters without having a new purpose or giving Dr. Seuss’s works new meaning.” And without “new expression, meaning or message” that alters Go!, ComicMix merely added “Star Trek material on top of what it meticulously copied” and failed to engage in transformative use. Helpfully, the court laid out three “benchmarks of transformative use,” which it gleaned from Campbell and Ninth Circuit precedent, to explain why Boldly was not transformative: “Boldly possesses none of these qualities; it merely repackaged Go!.”

First, the “telltale signs of transformative use” include a “‘further purpose or different character’ in the defendant’s work, i.e., ‘the creation of new information, new aesthetic, new insights and understanding.’” The court found that Boldly had neither a further purpose nor a different character since it paralleled the purpose of Go! and propounded its same message. Without a “new purpose or character” that would make it transformative, the court found that Boldly “merely recontextualized the original expression by ‘plucking the most visually arresting excerpt[s].”

The second of the “telltale signs” looks for “‘new expression, meaning, or message’ in the original work, i.e., the addition of ‘value to the original.’” The court found that ComicMix likewise failed to do this: “While Boldly may have altered Star Trek by sending Captain Kirk and his crew to a strange new world, that world, the world of Go!, remains intact.” The court’s focus was on whether Boldly changed Go! itself or merely repackaged it into a new format. Here, “Boldly does not change Go!,” and ComicMix’s admission that it could have used another work as the basis of its mash-up indicated that “Go! was selected ‘to get attention or to avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh,’ and not for a transformative purpose.”

The last of the “telltale signs” considers “the use of quoted matter as ‘raw material,’ instead of repackaging it and ‘merely supersed[ing] the objects of the original creation.’” The court, embedding several side-by-side images into the opinion to demonstrate the point, found that Boldly merely repackaged Go!. For the illustrations, the “Star Trek characters step into the shoes of Seussian characters in a Seussian world that is otherwise unchanged.” And for the text, rather than “using the Go! story as a starting point for a different artistic or aesthetic expression,” ComicMix instead matched its structure in a way that “did not result in the Go! story taking on a new expression, meaning, or message.” Since Boldly “left the inherent character of the [book] unchanged, it was not a transformative use of Go!.”

The court concluded that, “[a]lthough ComicMix’s work need not boldly go where no one has gone before, its repackaging, copying, and lack of critique of Seuss, coupled with its commercial use of Go!, does not result in a transformative use.” The first fair use factor thus “weigh[ed] definitively against fair use,” and the court went on to find that the other three factors favored Suess as well—without transformativeness to drive the analysis, ComicMix could not get the court to put its thumb on the scale in favor of fair use. Importantly, the court also rejected the holding below that the burden of proving likely market harm rested on Seuss: “the Supreme Court and our circuit have unequivocally placed the burden of proof on the proponent of the affirmative defense of fair use.” Additionally, the court chastised ComicMix for failing to address the “crucial right” of “the derivative works market,” noting that Boldly would likely “curtail Go!’s potential market for derivative works,” especially given that Seuss had “engaged extensively for decades” in this area.

Conclusion

All-in-all, the Ninth Circuit’s decision is a welcome development to the doctrine of fair use. Since Campbell was handed down over one-quarter of a century ago, the notion of transformativeness has taken on a central role—one that appears to be shrinking the exclusive right to prepare derivative works while expanding what it means to be transformative fair use. The accused work at issue here—Boldly—used the original work to create new expression, but lacking was any justification for the taking. ComicMix could have used any number of works for its mash-up, and the same nontransformative repackaging would have occurred because ComicMix’s purpose would not be tied to the particular work onto which it transposed the Star Trek universe. Thankfully, the Ninth Circuit was able to distinguish the transformative nature of a derivative work from the transformativeness that constitutes fair use. And given the prevalence of mash-ups in today’s culture, one suspects that this opinion will be cited and expanded upon for many years.

By Liz Velander

By Liz Velander By Chris Wolfsen

By Chris Wolfsen By Liz Velander

By Liz Velander By Meghan Carlin

By Meghan Carlin By Chris Wolfsen

By Chris Wolfsen

You might think that a copyright battle waged between tech behemoths Google LLC and Oracle America Inc. about computer code has little to do with the concerns of songwriters, authors, photographers, graphic artists, photo journalists and filmmakers. You would be wrong. These groups all filed amicus briefs with the U.S. Supreme Court in Google v. Oracle, argued on Wednesday Oct. 7.

You might think that a copyright battle waged between tech behemoths Google LLC and Oracle America Inc. about computer code has little to do with the concerns of songwriters, authors, photographers, graphic artists, photo journalists and filmmakers. You would be wrong. These groups all filed amicus briefs with the U.S. Supreme Court in Google v. Oracle, argued on Wednesday Oct. 7. By Bradfield Biggers

By Bradfield Biggers