Cross-posted from the Law Theories blog.

As readers are likely aware, the jury verdict in BMG v. Cox was handed down on December 17th. The jury found that BMG had proved by a preponderance of the evidence that Cox’s users were direct infringers and that Cox is contributorily liable for that infringement. The interesting thing, to me at least, about these findings is that they were both proved by circumstantial evidence. That is, the jury inferred that Cox’s users were direct infringers and that Cox had the requisite knowledge to make it a contributory infringer. Despite all the headlines about smoking-gun emails from Cox’s abuse team, the case really came down a matter of inference.

Direct Infringement of the Public Distribution Right

Section 106(3) grants copyright owners the exclusive right “to distribute copies . . . of the copyrighted work to the public[.]” In the analog days, a copy had to first be made before it could be distributed, and this led to much of the case law focusing on the reproduction right. However, in the digital age, the public distribution usually occurs before the reproduction. In an upload-download scenario, the uploader publicly distributes the work and then the downloader makes the copy. This has brought much more attention to the contours of the public distribution right, and there are some interesting splits in the case law looking at online infringement.

Though from the analog world, there is one case that is potentially binding authority here: Hotaling v. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Handed down by the Fourth Circuit in 1997, Hotaling held that “a library distributes a published work . . . when it places an unauthorized copy of the work in its collection, includes the copy in its catalog or index system, and makes the copy available to the public.” The copies at issue in Hotaling were in microfiche form, and they could not be checked out by patrons. This meant that the plaintiff could not prove that the library actually disseminated the work to any member of the public. Guided by equitable concerns, the Fourth Circuit held that “a copyright holder would be prejudiced by a library that does not keep records of public use,” thus allowing the library to “unjustly profit by its own omission.”

Whether this aspect of Hotaling applies in the digital realm has been a point of contention, and the courts have been split on whether a violation of the public distribution right requires actual dissemination. As I’ve written about before, the Nimmer on Copyright treatise now takes the position that “[n]o consummated act of actual distribution need be demonstrated in order to implicate the copyright owner’s distribution right,” but that view has yet to be universally adopted. Regardless, even if actual dissemination is required, Hotaling can be read to stand for the proposition that it can be proved by circumstantial evidence. As one court put it, “Hotaling seems to suggest” that “evidence that a defendant made a copy of a work available to the public might, in conjunction with other circumstantial evidence, support an inference that the copy was likely transferred to a member of the public.”

The arguments made by BMG and Cox hashed out this now-familiar landscape. Cox argued that merely offering a work to the public is not enough: “Section 106(3) makes clear that Congress intended not to include unconsummated transactions.” It then distinguished Hotaling on its facts, suggesting that, unlike the plaintiff there, BMG was “in a position to gather information about alleged infringement, even if [it] chose not to.” In opposition, BMG pointed to district court cases citing Hotaling, as well as to the Nimmer treatise, for the proposition that making available is public distribution simpliciter.

As to Cox’s attempt to distinguish Hotaling on the facts, BMG argued that Cox was the one that failed “to record actual transmissions of infringing works by its subscribers over its network.” Furthermore, BMG argued that “a factfinder can infer that the works at issue were actually shared from the evidence that they were made available,” and it noted that cases Cox had relied on “permit the inference that dissemination actually took place.” In its reply brief, Cox faulted BMG for reading Hotaling so broadly, but it noticeably had nothing to say about the propriety of inferring that dissemination had actually taken place.

In his memorandum opinion issued on December 1st, District Judge Liam O’Grady sided with Cox on the making available issue and with BMG on the permissibility of inference. Reading Hotaling narrowly, Judge O’Grady held that the Fourth Circuit merely “articulated a principle that applies only in cases where it is impossible for a copyright owner to produce proof of actual distribution.” And without the making available theory on the table, “BMG must show an actual dissemination of a copyrighted work.” Nonetheless, Judge O’Grady held that the jury could infer actual dissemination based on the circumstantial evidence collected by BMG’s agent, Rightscorp:

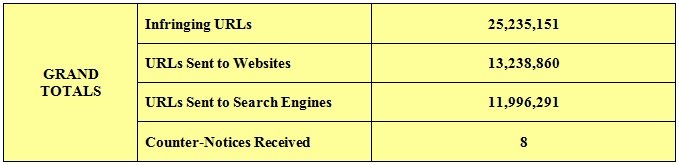

Cox’s argument ignores the fact that BMG may establish direct infringement using circumstantial evidence that gives rise to an inference that Cox account holders or other authorized users accessed its service to directly infringe. . . . Rightscorp claims to have identified 2.5 million instances of Cox users making BMG’s copyrighted works available for download, and Rightscorp itself downloaded approximately 100,000 full copies of BMG’s works using Cox’s service. BMG has presented more than enough evidence to raise a genuine issue of material fact as to whether Cox account holders directly infringed its exclusive rights.

The jury was ultimately swayed by this circumstantial evidence, inferring that BMG had proved that it was more likely than not that Cox’s users had actually disseminated BMG’s copyrighted works. But proving direct infringement is only the first step, and BMG next had to demonstrate that Cox is contributorily liable for that infringement. As we’ll see, this too was proved by inference.

Contributory Infringement of the Public Distribution Right

While the Patent Act explicitly provides circumstances in which someone “shall be liable as a contributory infringer,” the Copyright Act’s approach is much less direct. As I’ve written about before, the entire body of judge-made law concerning secondary liability was imported into the 1976 Act via the phrase “to authorize” in Section 106. Despite missing this flimsy textual hook, the Supreme Court held in Sony that nothing precludes “the imposition of liability for copyright infringements on certain parties who have not themselves engaged in the infringing activity.” Indeed, the Court noted that “the concept of contributory infringement is merely a species of the broader problem of identifying the circumstances in which it is just to hold one individual accountable for the actions of another.”

Arguments about when it’s “just” to hold someone responsible for the infringement committed by another have kept lawyers busy for well over a century. The Second Circuit’s formulation of the contributory liability test in Gershwin has proved particularly influential over the past four decades: “[O]ne who, with knowledge of the infringing activity, induces, causes or materially contributes to the infringing conduct of another, may be held liable as a ‘contributory’ infringer.” This test has two elements: (1) knowledge, and (2) induce, cause, or materially contribute. Of course, going after the service provider, as opposed to going after the individual direct infringers, often makes sense. The Supreme Court noted this truism in Grokster:

When a widely shared service or product is used to commit infringement, it may be impossible to enforce rights in the protected work effectively against all direct infringers, the only practical alternative being to go against the distributor of the copying device for secondary liability on a theory of contributory or vicarious infringement.

And this is what BMG has done here by suing Cox instead of Cox’s users. The Supreme Court in Grokster also introduced a bit of confusion into the contributory infringement analysis. The theory at issue there was inducement—the plaintiffs argued that Grokster induced its users to infringe. Citing Gershwin, the Supreme Court stated this test: “One infringes contributorily by intentionally inducing or encouraging direct infringement[.]” Note how this is narrower than the test in Gershwin, which for the second element also permits causation or material contribution. While, on its face, this can plausibly be read to imply a narrowing of the traditional test for contributory infringement, the better read is that the Court merely mentioned the part of the test (inducement) that it was applying.

Nevertheless, Cox argued here that Grokster jettisoned a century’s worth of the material contribution flavor of contributory infringement: “While some interpret Grokster as creating a distinct inducement theory, the Court was clear: Grokster is the contributory standard.” Cox wanted the narrower inducement test to apply here because BMG would have a much harder time proving inducement over material contribution. As such, Cox focused on its lack of inducing behavior, noting that it did not take “any active steps to foster infringement.”

Despite its insistence that “Grokster supplanted the earlier Gershwin formulation,” Cox nevertheless argued that BMG’s anticipated material contribution claim “fails as a matter of law” since the knowledge element could not be proved. According to Cox, “Rightscorp’s notices do not establish Cox’s actual knowledge of any alleged infringement because notices are merely allegations of infringement[.]” Nor does the fact that it refused to receive notices from Rightscorp make it “willfully blind to copyright infringement on its network.” Cox didn’t argue that its service did not materially contribute to the infringement, and rightfully so—the material contribution element here is a no-brainer.

In opposition, BMG focused on Gershwin, declaring it to be “the controlling test for contributory infringement.” BMG noted that “Cox is unable to cite a single case adopting” its narrow “reading of Grokster, under which it would have silently overruled forty years of contributory infringement case law” applying Gershwin. (Indeed, I have yet to see a single court adopt Cox’s restrictive read of Grokster. This hasn’t stopped defendants from trying, though.) Turning to the material contribution element, BMG pointed out that “Cox does not dispute that it materially contributed to copyright infringement by its subscribers.” Again, Cox didn’t deny material contribution because it couldn’t win on this argument—the dispositive issue here is knowledge.

On the knowledge element, BMG proffered two theories. The first was that Cox is deemed “to have knowledge of infringement on its system where it knows or has reason to know of the infringing activity.” Here, BMG had sent Cox “millions of notices of infringement,” and it argued that Cox could not “avoid knowledge by blacklisting, deleting, or refusing” to accept its notices. Moreover, BMG noted that “Cox’s employees repeatedly acknowledged that they were aware of widespread infringement on Cox’s system.” BMG additionally argued that Cox was willfully blind since it “blacklisted or blocked every single notice of copyright infringement sent by Rightscorp on behalf of Plaintiffs, in an attempt to avoid specific knowledge of any infringement.”

In reply, Cox cited Sony for the rule that “a provider of a technology could not be liable for contributory infringement arising from misuse if the technology is capable of substantial noninfringing uses.” And since Cox’s service “is capable of substantial noninfringing users,” it claimed that it “cannot be liable under Sony.” Of course, as the Supreme Court clarified in Grokster, that is not the proper way to read Sony. Sony merely says that knowledge cannot be imputed because a service has some infringing uses. But BMG here is not asking for knowledge to be imputed based on the design of Cox’s service. It’s asking for knowledge to be inferred from the notices that Cox refused to receive.

Judge O’Grady made short work of Cox’s arguments. He cited Gershwin as the controlling law and rejected Cox’s argument vis-à-vis Grokster: “The Court finds no support for Cox’s reading of Grokster.” In a footnote, he brushed aside any discussion of whether Cox materially contributed to the infringement since Cox failed to raise the point in its initial memorandum. Judge O’Grady then turned to the knowledge element, stating the test as this: “The knowledge requirement is met by a showing of actual or constructive knowledge or by evidence that a defendant took deliberate actions to willfully blind itself to specific infringing activity.” In a footnote, he declined to follow the narrower rule in the Ninth Circuit from Napster that requires the plaintiff to establish “actual knowledge of specific acts of infringement.”

Thus, Judge O’Grady held that three types of knowledge were permissible to establish contributory infringement: (1) actual knowledge (“knew”), (2) constructive knowledge (“had reason to know”), or (3) willful blindness. Rejecting Cox’s theory to the contrary, he held that “DMCA-compliant notices are evidence of knowledge.” The catch here was that Cox refused to receive them, and it even ignored follow-up emails from BMG. And this is where inference came into play: Judge O’Grady held that Cox could have constructive knowledge since “a reasonable jury could conclude that Cox’s refusal to accept Rightscorp’s notices was unreasonable and that additional notice provided to Cox gave it reason to know of the allegedly infringing activity on its network.”

Turning to willful blindness, Judge O’Grady stated that it “requires more than negligence or recklessness.” Citing Global-Tech, he noted that BMG must prove that Cox “took ‘deliberate actions to avoid confirming a high probability of wrongdoing and who can almost be said to have actually known the critical facts.’” The issue here was clouded by the fact that Cox didn’t simply refuse to accept BMG’s notices from Rightscorp, but instead it offered to receive them if certain language offering settlements to Cox’s users was removed. While it would be reasonable to infer that Cox was not “deliberately avoiding knowledge of illegal activity,” Judge O’Grady held that “it is not the only inference available.” As such, he left it for the jury to decide as a question of fact which inference was better.

The jury verdict is now in, and we don’t know whether the jury found for BMG on the constructive knowledge theory or the willful blindness theory—or perhaps even both. Either way, the question boiled down to one of inference, and the jury was able to infer knowledge on Cox’s part. And this brings us back to the power of inference. Cox ended up being found liable as a contributory infringer for its users’ direct infringement of BMG’s public distribution rights, and both of these verdicts were established with nothing more than circumstantial evidence. That’s the power of inference when it comes to ISP liability.

This past Friday, the Board of Immigration Appeals held that criminal copyright infringement constitutes a “crime involving moral turpitude” under immigration law. The Board reasoned that criminal copyright infringement is inherently immoral because it involves the willful theft of property and causes harm to both the copyright owner and society.

This past Friday, the Board of Immigration Appeals held that criminal copyright infringement constitutes a “crime involving moral turpitude” under immigration law. The Board reasoned that criminal copyright infringement is inherently immoral because it involves the willful theft of property and causes harm to both the copyright owner and society. In 2013, CPIP published a policy brief by Professor Bruce Boyden exposing the DMCA notice and takedown system as outdated and in need of reform.

In 2013, CPIP published a policy brief by Professor Bruce Boyden exposing the DMCA notice and takedown system as outdated and in need of reform.

We’ve released a new policy brief,

We’ve released a new policy brief,