By Andrew Baluch[1] & Devlin Hartline

By Andrew Baluch[1] & Devlin Hartline

President Donald Trump will soon announce his nominee to fill the vacancy left at the Supreme Court by late Associate Justice Antonin Scalia. On September 23, 2016, the Trump campaign revealed that there are twenty-one candidates under consideration for the nomination.

Below is a summary of the intellectual property backgrounds of President Trump’s twenty-one potential Supreme Court nominees. The summary addresses judicial, legislative, and legal experience, as well as education and scholarly work. The summary includes data on each nominee’s intellectual property cases, whether decided as a judge or argued in private practice. Where appropriate, the summary also notes legislative bills that were co-sponsored by the nominee.

Click on the nominee’s name in the table below to jump down to their detailed summary.

| SUMMARY OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY CASES |

|

|

Cases Decided as Judge |

Cases Argued in Private Practice |

| No. |

Nominee |

Patent |

Trademark |

Copyright |

Trade Secret |

Patent |

Trademark |

Copyright |

Trade Secret |

| 1 |

Blackwell, Keith |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

Canady, Charles |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 3 |

Colloton, Steven |

2 |

9 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 4 |

Eid, Allison |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 5 |

Gorsuch, Neil |

0 |

7 |

4 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 6 |

Gruender, Raymond |

0 |

5 |

7 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 7 |

Hardiman, Thomas |

1 |

6 |

5 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 8 |

Kethledge, Raymond |

0 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 9 |

Larsen, Joan |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 10 |

Lee, Mike |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 11 |

Lee, Thomas |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

27 |

2 |

1 |

| 12 |

Mansfield, Edward |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 13 |

Moreno, Federico |

3 |

15 |

9 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 14 |

Pryor, William |

0 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 15 |

Ryan, Margaret |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 16 |

Stras, David |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 17 |

Sykes, Diane |

4 |

5 |

8 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 18 |

Thapar, Amul |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 19 |

Tymkovich, Timothy |

1 |

5 |

6 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 20 |

Willett, Don |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 21 |

Young, Robert |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1. Keith R. Blackwell

Supreme Court of Georgia (2012 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

Court of Appeals of Georgia (2010 – 2012)

Prior Legal Experience

Parker, Hudson, Rainer & Dobbs LLP; Assistant District Attorney, Cobb County, GA; Alston & Bird LLP; Law Clerk to Judge J.L. Edmondson (11th Circuit)

Education

JD, University of Georgia School of Law (1999); BA, University of Georgia (1996)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

1 total (in favor of owner) |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Case: Kremer v. Tea Party Patriots, Inc., 314 Ga. App. 459 (2012)

Back to top.

2. Charles T. Canady

Florida Supreme Court (2008 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

Florida Second District Court of Appeal (2002 – 2008)

Prior Legislative Experience

U.S. Representative (R-FL) (1993 – 2001) (House Judiciary Committee); Florida House of Representatives (1984 – 1990)

Prior Legal Experience

General Counsel to Florida Governor Jeb Bush; Lane, Trohn, Clarke, Bertrand & Williams, PA; Holland & Knight

Intellectual Property Bills Co-Sponsored as U.S. Representative

Co-sponsored 13 bills involving intellectual property, including: 104th-H.R.1733, Patent Application Publication Act of 1995 (introduced); 104th-H.R.1127, Medical Procedures Innovation and Affordability Act (introduced); 104th-H.R.587, Biotechnological Process Patents (passed House); 104th-H.R.359, Patent Term Restoration (introduced)

Education

JD, Yale Law School (1979); BA, Haverford College (1976)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

1 total (in favor of malpractice defendant law firm and against client patentee) |

| Trademark |

2 total (all in favor of owner) |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Cases: Larson & Larson, P.A. v. TSE Indus., Inc., 22 So. 3d 36 (Fla. 2009); Florida Virtual Sch. v. K12, Inc., 148 So. 3d 97 (Fla. 2014); Rooney v. Skeet’r Beat’r Of Sw. Florida, Inc., 898 So. 2d 968 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2005)

Back to top.

3. Steven M. Colloton

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit (2003 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

U.S. Attorney, Southern District of Iowa; Adjunct Lecturer, University of Iowa College of Law; Private Practice, Iowa; Associate Independent Counsel, Office of Independent Counsel Kenneth W. Starr; Assistant U.S. Attorney, Northern District of Iowa; Special Assistant to the Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel; Law Clerk to Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist (U.S. Supreme Court); Law Clerk to Judge Laurence H. Silberman (D.C. Circuit)

Education

JD, Yale Law School (1988); BA, Princeton University (1985)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

2 total (all in favor of infringer) |

| Trademark |

9 total (7 in favor of owner; 2 in favor of infringer) |

| Copyright |

1 total (in favor of owner) |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Cases: Andover Healthcare, Inc. v. 3M Co., 817 F.3d 621 (8th Cir. 2016); Schinzing v. Mid-States Stainless, Inc., 415 F.3d 807 (8th Cir. 2005); B & B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis Indus., Inc., 716 F.3d 1020 (8th Cir. 2013); C.B.C. Distribution & Mktg., Inc. v. Major League Baseball Advanced Media, L.P., 505 F.3d 818 (8th Cir. 2007); Coca-Cola Co. v. Purdy, 382 F.3d 774 (8th Cir. 2004); Faegre & Benson, LLP v. Purdy, 129 F. App’x 323 (8th Cir. 2005); Gateway, Inc. v. Companion Prod., Inc., 384 F.3d 503 (8th Cir. 2004); Mid-State Aftermarket Body Parts, Inc. v. MQVP, Inc., 466 F.3d 630 (8th Cir. 2006); Sensient Techs. Corp. v. SensoryEffects Flavor Co., 613 F.3d 754 (8th Cir. 2010); Lovely Skin, Inc. v. Ishtar Skin Care Prod., LLC, 745 F.3d 877 (8th Cir. 2014); Pangaea, Inc. v. Flying Burrito LLC, 647 F.3d 741 (8th Cir. 2011); Capitol Records, Inc. v. Thomas-Rasset, 692 F.3d 899 (8th Cir. 2012)

Back to top.

4. Allison H. Eid

Colorado Supreme Court (2006 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

Solicitor General, State of Colorado; Associate Professor, University of Colorado School of Law; Arnold & Porter; Law Clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas (U.S. Supreme Court); Law Clerk to Judge Jerry E. Smith (5th Circuit)

Education

JD, University of Chicago Law School (1991); BA, Stanford University (1987)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

1 total (dissenting in favor of infringer) |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 (but in 1 case analogizing to patent law for “full compensation” damages) |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Case: Acoustic Mktg. Research, Inc. v. Technics, LLC, 198 P.3d 96 (Colo. 2008)

Back to top.

5. Neil M. Gorsuch

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit (2006 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

Principal Deputy to U.S. Associate Attorney General; Kellogg, Huber, Hansen, Todd & Evans; Law Clerk to Justice Byron R. White and Justice Anthony M. Kennedy (U.S. Supreme Court); Law Clerk to Judge David B. Sentelle (D.C. Circuit)

Education

DPhil, Oxford University (2004); JD, Harvard Law School (1991); BA, Columbia University (1988)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

7 total (2 in favor of owner; 5 in favor of infringer) |

| Copyright |

4 total (all in favor of infringer) |

| Trade Secret |

3 total (2 in favor of owner; 1 in favor of infringer) |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Cases: Earthgrains Baking Companies Inc. v. Sycamore Family Bakery, Inc., 573 F. App’x 676 (10th Cir. 2014); Gen. Steel Domestic Sales, LLC v. Chumley, 627 F. App’x 682 (10th Cir. 2015); Lorillard Tobacco Co. v. Engida, 611 F.3d 1209 (10th Cir. 2010); Hargrave v. Chief Asian, LLC, 479 F. App’x 827 (10th Cir. 2012); Surefoot LC v. Sure Foot Corp., 531 F.3d 1236 (10th Cir. 2008); Utah Lighthouse Ministry v. Found. for Apologetic Info. & Research, 527 F.3d 1045 (10th Cir. 2008); Blehm v. Jacobs, 702 F.3d 1193 (10th Cir. 2012); Dudnikov v. Chalk & Vermilion Fine Arts, Inc., 514 F.3d 1063 (10th Cir. 2008); La Resolana Architects, PA v. Reno, Inc., 555 F.3d 1171 (10th Cir. 2009); Meshwerks, Inc. v. Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A., Inc., 528 F.3d 1258 (10th Cir. 2008); Russo v. Ballard Med. Prod., 550 F.3d 1004 (10th Cir. 2008); Storagecraft Tech. Corp. v. Kirby, 744 F.3d 1183 (10th Cir. 2014)

Back to top.

6. Raymond W. Gruender

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit (2004 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

U.S. Attorney, Eastern District of Missouri; Thompson Coburn LLP; Assistant U.S. Attorney, Eastern District of Missouri; Lewis Rice & Fingersh

Education

JD, Washington University (1987); MBA, Washington University (1987), BA, Washington University (1984)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

5 total (5 in favor of owner |

| Copyright |

7 total (4 in favor of owner; 3 in favor of infringer) |

| Trade Secret |

2 total (1 in favor of owner; 1 in favor of infringer) |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

1 total (amicus brief on behalf of U.S. Copyright Office) |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Cases: Dryer v. Nat’l Football League, 814 F.3d 938 (8th Cir. 2016); First Nat. Bank in Sioux Falls v. First Nat. Bank S. Dakota, 679 F.3d 763 (8th Cir. 2012); Jones v. W. Plains Bank & Trust Co., 813 F.3d 700 (8th Cir. 2015); Kforce, Inc. v. Surrex Sols. Corp., 436 F.3d 981 (8th Cir. 2006); Lovely Skin, Inc. v. Ishtar Skin Care Prod., LLC, 745 F.3d 877 (8th Cir. 2014); Pearson Educ., Inc. v. Almgren, 685 F.3d 691 (8th Cir. 2012); Pinnacle Pizza Co. v. Little Caesar Enterprises, Inc., 598 F.3d 970 (8th Cir. 2010); Strange Music, Inc. v. Anderson, 419 F. App’x 707 (8th Cir. 2011); United States v. Frison, 825 F.3d 437 (8th Cir.); United States v. Sweeney, 611 F.3d 459 (8th Cir. 2010); Warner Bros. Entm’t v. X One X Prods., 644 F.3d 584 (8th Cir. 2011); Warner Bros. Entm’t v. X One X Prods., 840 F.3d 971 (8th Cir. 2016); Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v. WMR e-PIN, LLC, 653 F.3d 702 (8th Cir. 2011)

Back to top.

7. Thomas M. Hardiman

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit (2007 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

U.S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania (2003 – 2007)

Prior Legal Experience

Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom; Titus & McConomy LLP; Reed Smith LLP

Education

JD, Georgetown University Law Center (1990); BA, University of Notre Dame (1987)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

1 total (in favor of negligent law firm) |

| Trademark |

6 total (5 in favor of owner; 1 in favor of infringer) |

| Copyright |

5 total (3 in favor of owner; 2 in favor of infringer) |

| Trade Secret |

3 total (1 in favor of owner; 2 in favor of infringer) |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Cases: Ackourey v. Sonellas Custom Tailors, 573 F. App’x 208 (3d Cir. 2014); Am. Bd. of Internal Med. v. Von Muller, 540 F. App’x 103 (3d Cir. 2013); Avaya Inc., RP v. Telecom Labs, Inc., 838 F.3d 354 (3d Cir. 2016); Boyle v. United States, 391 F. App’x 212 (3d Cir. 2010); Brand Mktg. Grp. LLC v. Intertek Testing Servs., N.A., Inc., 801 F.3d 347 (3d Cir. 2015); Dow Chem. Canada, Inc. v. HRD Corp., 587 F. App’x 741 (3d Cir. 2014); FedEx Ground Package Sys. v. Applications Int’l Corp., 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 26651 (W.D. Pa. Nov. 4, 2005); Fishkin v. Susquehanna Partners, G.P., 340 F. App’x 110 (3d Cir. 2009); Groupe SEB USA, Inc. v. Euro-Pro Operating LLC, 774 F.3d 192 (3d Cir. 2014); Aslam v. Attorney Gen. of U.S., 404 F. App’x 599 (3d Cir. 2010); Sims v. Viacom, Inc., 544 F. App’x 99 (3d Cir. 2013); Singer Mgmt. Consultants, Inc. v. Milgram, 650 F.3d 223 (3d Cir. 2011); United States v. Diallo, 476 F. Supp. 2d 497 (W.D. Pa. 2007), aff’d, 575 F.3d 252 (3d Cir. 2009); William A. Graham Co. v. Haughey, 568 F.3d 425 (3d Cir. 2009); World Entm’t Inc. v. Brown, 487 F. App’x 758 (3d Cir. 2012)

Back to top.

8. Raymond M. Kethledge

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (2008 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

Bush Seyferth & Paige PLLC; Feeney Kellett Wienner & Bush PC; Counsel, Ford Motor Company; Honigman, Miller, Schwartz & Cohn LLP; Law Clerk to Justice Anthony Kennedy (U.S. Supreme Court); Judiciary Counsel to U.S. Senator Spencer Abraham (R-MI); Law Clerk to Judge Ralph B. Guy, Jr. (6th Circuit)

Education

JD, University of Michigan Law School (1993); BA, University of Michigan (1989)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

4 total (3 in favor of owner; 1 in favor of infringer) |

| Copyright |

2 total (1 in favor of owner; 1 in favor of infringer) |

| Trade Secret |

1 total (in favor of infringer) |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

5 total (all on behalf of infringer/generic pharmaceutical company) |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret: |

0 |

Cases: Kerr Corp. v. Freeman Mfg. & Supply Co., 2009 U.S. App. LEXIS 6342 (6th Cir. Ohio 2009); Sony/ATV Publ’g, LLC v. Marcos, 651 F. App’x 482 (6th Cir. 2016); L.F.P.IP, LLC v. Hustler Cincinnati, Inc., 533 F. App’x 615 (6th Cir. 2013); Nagler v. Garcia, 370 F. App’x 678 (6th Cir. 2010); R.C. Olmstead, Inc., v. CU Interface, LLC, 606 F.3d 262 (6th Cir. 2010); Taylor v. Thomas, 624 F. App’x 322 (6th Cir. 2015); In re Desloratadine Patent Litig., 502 F. Supp. 2d 1354 (U.S. Jud. Pan. Mult. Lit. 2007); PDL BioPharma, Inc. v. Sun Pharm. Indus., 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 56948 (E.D. Mich. Aug. 6, 2007); Schering Corp. v. Caraco Pharm. Labs., Ltd., 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 41020 (E.D. Mich. June 6, 2007); Sun Pharm. Indus. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 35206 (E.D. Mich. Apr. 30, 2008); Sun Pharm. Indus. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 46730 (E.D. Mich. June 16, 2008)

Back to top.

9. Joan L. Larsen

Michigan Supreme Court (2015 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

Adjunct Professor, University of Michigan Law School; Deputy Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel; Visiting Assistant Professor, Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law; Sidley Austin LLP; Law Clerk to Justice Antonin Scalia (U.S. Supreme Court); Law Clerk to Judge David B. Sentelle (D.C. Circuit)

Education

JD, Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law (1993); BA, University of Northern Iowa (1990)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Back to top.

10. Michael S. Lee

U.S. Senator (R-UT) (2011 – present)

Prior Legislative Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

Howrey LLP; Law Clerk to Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr. (U.S. Supreme Court); General Counsel to Utah Governor Jon Huntsman; Assistant U.S. Attorney, District of Utah; Sidley Austin LLP; Law Clerk to Judge Samuel A. Alito, Jr. (3rd Circuit); Law Clerk to Judge Dee Benson (D. Utah)

Intellectual Property Bills Co-Sponsored as U.S. Senator

Co-sponsored 6 bills involving intellectual property: 114th-S.2733, VENUE Act (introduced); 114th-S.1137, PATENT Act (introduced and voted yes); 113th-S.1720, Patent Transparency and Improvements Act of 2013 (introduced); 114th-S.328, A bill to amend the Trademark Act of 1946 to provide for the registration of marks consisting of a flag, coat of arms, or other insignia of the United States, or any State or local government (introduced); 113th-S.1816, A bill to amend the Trademark Act of 1946 to provide for the registration of marks consisting of a flag, coat of arms, or other insignia of the United States, or any State or local government (introduced); 113th-S.517, Unlocking Consumer Choice and Wireless Competition Act (became law)

Education

JD, Brigham Young University Law School (1997); BS, Brigham Young University (1994)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

N/A |

| Trademark |

N/A |

| Copyright |

N/A |

| Trade Secret |

N/A |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

1 total (on behalf of infringer Deutsche Bank) |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Case: Island Intellectual Prop. LLC v. Deutsche Bank Trust Co. Americas, 2012 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 15212 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 10, 2012)

Back to top.

11. Thomas R. Lee

Utah Supreme Court (2010 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

Deputy Assistant Attorney General, Civil Division; Rex & Maureen Rawlinson Professor of Law, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University; Howard, Phillips & Anderson LLC; Parr Brown Gee & Loveless, PC; Law Clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas (U.S. Supreme Court); Law Clerk to Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson, III (4th Circuit)

Scholarly Articles on Intellectual Property

Thomas R. Lee, et. al., An Empirical and Consumer Psychology Analysis of Trademark Distinctiveness, 41 Ariz. St. L.J. 1033 (2009); Thomas R. Lee, et. al., Sophistication, Bridging the Gap, and the Likelihood of Confusion: An Empirical and Theoretical Analysis, 98 Trademark Rep. 913 (2008); Thomas R. Lee, et. al., Trademarks, Consumer Psychology, and the Sophisticated Consumer, 57 Emory L.J. 575 (2008); Thomas R. Lee, Demystifying Dilution, 84 B.U. L. Rev. 859 (2004); Thomas R. Lee, Eldred v. Ashcroft and the (Hypothetical) Copyright Term Extension Act of 2020, 12 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 1 (2003); Thomas R. Lee, et. al. “To Promote the Progress of Science”: The Copyright Clause and Congress’s Power to Extend Copyrights, 16 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 1 (2002); Thomas R. Lee, In Rem Jurisdiction in Cyberspace, 75 Wash. L. Rev. 97 (2000) (proposing an “in rem” solution to the problem of cyberpiracy)

Education

JD, University of Chicago Law School (1991); BA, Brigham Young University (1988)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

3 total (all in favor of owner) |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

27 total (all on behalf of owner) |

| Copyright |

2 total (1 on behalf of owner; 1 on behalf of infringer) |

| Trade Secret |

1 total (on behalf of infringer) |

Cases: InnoSys, Inc. v. Mercer, 364 P.3d 1013 (Utah 2015); Legacy Res., Inc. v. Liberty Pioneer Energy Source, Inc., 322 P.3d 683 (Utah 2013); USA Power, LLC v. PacifiCorp, 372 P.3d 629 (Utah 2016)

Back to top.

12. Edward M. Mansfield

Iowa Supreme Court (2011 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

Iowa Court of Appeals (2009 – 2011)

Prior Legal Experience

Belin Lamson McCormick Zumbach & Flynn, PC; Lewis Roca Rothgerber Christie LLP; Adjunct Professor, Drake University Law School; Law Clerk to Judge Patrick Higginbotham (5th Circuit)

Education

JD, Yale Law School (1982); BA, Harvard University (1978)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

1 total (on behalf of owner) |

| Trademark |

1 total (on behalf of infringer) |

| Copyright |

1 total (on behalf of infringer) |

| Trade Secret |

1 total (on behalf of owner) |

Cases: Kemin Foods, L.C. v. Pigmentos Vegetales del Centro S.A. de C.V., 384 F. Supp. 2d 1334 (S.D. Iowa 2005), aff’d, 464 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2006); Amerus Group Co. v. Ameris Bancorp, 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 32722 (S.D. Iowa May 22, 2006); Ryan v. Editions Ltd. West, Inc., 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 131652 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 23, 2016); Midwest Oilseeds, Inc. v. Limagrain Genetics Corp., 2002 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 28698 (S.D. Iowa Nov. 8, 2002)

Back to top.

13. Federico A. Moreno

U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida (1990 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

Eleventh Judicial Circuit of Florida (1987 – 1990); Miami-Dade County Court (1986 – 1987)

Prior Legal Experience

Thornton, Rothman & Moreno, PA; Assistant Federal Public Defender, Southern District of Florida; Rollins, Peeples & Meadows, PA

Education

JD, University of Miami School of Law (1978); BA, University of Notre Dame (1974)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

3 (1 in favor of owner; 2 in favor of infringer) |

| Trademark |

15 (11 in favor of owner; 4 in favor of infringer) |

| Copyright |

9 (7 in favor of owner; 2 in favor of infringer) |

| Trade Secret |

3 (2 in favor of owner; 1 in favor of infringer) |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Cases: Allegiance Healthcare Corp. v. Coleman, 232 F. Supp. 2d 1329 (S.D. Fla. 2002); Biotanic, Inc. v. Vazquez, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 69048 (S.D. Fla. July 7, 2010); Burger King Corp. v. Weaver, 33 F. Supp. 2d 1037 (S.D. Fla. 1998); Carnival Corp. v. SeaEscape Casino Cruises, Inc., 74 F. Supp. 2d 1261 (S.D. Fla. 1999); Coach Servs. v. 777 Lucky Accessories, Inc., 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 67739 (S.D. Fla. June 16, 2010); Davis v. Raymond, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 68392 (S.D. Fla. May 13, 2013); Erika Boom & Belly & Kicks I, LLC v. Rosebandits, LLC, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 158528 (S.D. Fla. Nov. 5, 2013); CEyePartner, Inc. v. Kor Media Group LLC, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 98370 (S.D. Fla. July 15, 2013); Fuentes v. Mega Media Holdings, Inc., 721 F. Supp. 2d 1255 (S.D. Fla. 2010); HFuentes v. Mega Media Holdings, Inc., 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 5298 (S.D. Fla. Jan. 20, 2011); Gapardis Health & Beauty, Inc. v. Pramil S.R.L. (ESAPHARMA), 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 98005 (S.D. Fla. May 23, 2007); Gen. Cigar Holdings, Inc. v. Altadis, S.A., 205 F. Supp. 2d 1335 (S.D. Fla.); Glob. Innovation Tech. Holdings, LLC v. Acer Am. Corp., 634 F. Supp. 2d 1346 (S.D. Fla. 2009); Greenberg v. Miami Children’s Hosp. Research Inst., Inc., 264 F. Supp. 2d 1064 (S.D. Fla. 2003); MHermosilla v. Octoscope Music, LLC, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 129469 (S.D. Fla. Dec. 3, 2010); Icon Health & Fitness, Inc. v. IFITNESS, Inc., 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 46824 (S.D. Fla. Apr. 2, 2012); Inmuno Vital, Inc. v. Golden Sun, Inc., 49 F. Supp. 2d 1344 (S.D. Fla. 1997); HLorentz v. Sunshine Health Prods., 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 100985 (S.D. Fla. Sept. 23, 2010); Milk Money Music v. Oakland Park Entm’t Corp., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 121661 (S.D. Fla. Dec. 10, 2009); NPA Assocs., LLC v. Lakeside Portfolio Mgmt., LLC, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22805 (S.D. Fla. Feb. 22, 2014); Platypus Wear, Inc. v. Clarke Modet & Co., 515 F. Supp. 2d 1288 (S.D. Fla. 2007); Polvent v. Global Fine Arts, Inc., 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 130936 (S.D. Fla. Sept. 18, 2014); Promex, LLC v. Perez Distrib. Fresno, Inc., 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 90677 (S.D. Fla. Sept. 1, 2010); Setai Hotel Acquisitions, LLC v. Luxury Rentals Miami Beach, Inc., 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 171396 (S.D. Fla. Dec. 9, 2016); TNT USA, Inc v. TrafiExpress, S.A. de C.V., 434 F. Supp. 2d 1322 (S.D. Fla. 2006); SValeant Int’l (Barb.) SRL v. Watson Pharms., Inc., 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 193254 (S.D. Fla. July 6, 2012); Valeant Int’l (Barbados) SRL v. Watson Pharms., Inc., 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 128742 (S.D. Fla. Nov. 7, 2011); Valoro, LLC v. Valero Energy Corp., 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 110554 (S.D. Fla. Aug. 11, 2014); Y.Z.Y., Inc. v. Azmere USA Inc., 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 192674 (S.D. Fla. Oct. 16, 2013)

Back to top.

14. William H. Pryor, Jr.

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit (2004 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

Commissioner, U.S. Sentencing Commission; Visiting Professor, University of Alabama School of Law; Attorney General, Alabama; Deputy Attorney General, Alabama; Adjunct Professor, Samford University, Cumberland School of Law; Walston, Stabler, Wells, Anderson & Bains; Cabaniss, Johnston, Gardner, Dumas & O’Neal; Law Clerk to Judge John M. Wisdom (5th Circuit)

Education

JD, Tulane University School of Law (1987); BA, Northeast Louisiana University (1984)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

3 total (all in favor of owner) |

| Copyright |

3 total (all in favor of infringer) |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Cases: ADT LLC v. Alarm Prot. Tech. Florida, LLC, 646 F. App’x 781 (11th Cir. 2016); Genesys Software Sys. v. Ceridian Corp., 2016 U.S. App. LEXIS 20914 (11th Cir. Nov. 22, 2016); Jysk Bed’N Linen v. Dutta-Roy, 810 F.3d 767 (11th Cir. 2015); Latele TV, C.A. v. Telemundo Communs. Group, LLC, 2016 U.S. App. LEXIS 20345 (11th Cir. Fla. May 26, 2016); Navellier v. Fla., 2016 U.S. App. LEXIS 21473 (11th Cir. Fla. Dec. 1, 2016); Singleton v. Dean, 611 F. App’x 671 (11th Cir. 2015); Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes & of Malta v. Florida Priory of the Knights Hospitallers of the Sovereign Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, Knights of Malta, The Ecumenical Order, 809 F.3d 1171 (11th Cir. 2015)

Back to top.

15. Margaret A. Ryan

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces (2006 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

Wiley Rein LLP; Bartlit Beck Palenchar & Scott LLP; Cooper Carvin & Rosenthal; Law Clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas (U.S. Supreme Court); Law Clerk to Judge J. Michael Luttig (4th Circuit); Judge Advocate, U.S. Marine Corps

Education

JD, Notre Dame Law School (1995); BA, Knox College (1985)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Back to top.

16. David R. Stras

Minnesota Supreme Court (2010 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

Professor, University of Minnesota Law School; Faegre & Benson LLP; Sidley Austin Brown & Wood; Law Clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas (U.S. Supreme Court); Law Clerk to Judge J. Michael Luttig (4th Circuit); Law Clerk to Judge Melvin Brunetti (9th Circuit)

Education

JD, University of Kansas School of Law (1999); MBA, University of Kansas (1999); BA, University of Kansas (1995)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

1 total (in favor of owner) |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Case: Seagate Tech., LLC v. W. Digital Corp., 854 N.W.2d 750 (Minn. 2014)

Back to top.

17. Diane S. Sykes

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit (2004 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

Wisconsin Supreme Court (1999 – 2004); Wisconsin Circuit Court, Milwaukee County (1992 – 1999)

Prior Legal Experience

Whyte Hirschboeck & Dudek SC; Law Clerk to Judge Terence T. Evans (E.D. Wis.)

Education

JD, Marquette University Law School (1984); BS, Northwestern University (1980)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

4 total (3 in favor of owner; 1 in favor of infringer) |

| Trademark |

5 total (2 in favor of owner; 3 in favor of infringer) |

| Copyright |

8 total (4 in favor of owner; 4 in favor of infringer) |

| Trade Secret |

2 total (all in favor of infringer) |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Cases: Allan Block Corp. v. Cty. Materials Corp., 512 F.3d 912 (7th Cir. 2008); Bell v. Lantz, 825 F.3d 849 (7th Cir. 2016); Cent. Mfg., Inc. v. Brett, 492 F.3d 876 (7th Cir. 2007); Chicago Bldg. Design, P.C. v. Mongolian House, Inc., 770 F.3d 610 (7th Cir. 2014); Coach, Inc. v. DI DA Imp. & Exp., Inc., 630 F. App’x 632 (7th Cir. 2016); Consumer Health Info. Corp. v. Amylin Pharm., Inc., 819 F.3d 992 (7th Cir.); Edgenet, Inc. v. Home Depot U.S.A., Inc., 658 F.3d 662 (7th Cir. 2011); Furkin v. Smikun, 237 F. App’x 86 (7th Cir. 2007); Georgia-Pac. Consumer Prod. LP v. Kimberly-Clark Corp., 647 F.3d 723 (7th Cir. 2011); Grigoleit Co. v. Whirlpool Corp., 769 F.3d 966 (7th Cir. 2014); Hecny Transp., Inc. v. Chu, 430 F.3d 402 (7th Cir. 2005); Hyson USA, Inc. v. Hyson 2U, Ltd., 821 F.3d 935 (7th Cir. 2016); Kelley v. Chicago Park Dist., 635 F.3d 290 (7th Cir. 2011); Mostly Memories, Inc. v. For Your Ease Only, Inc., 526 F.3d 1093 (7th Cir. 2008); nClosures Inc. v. Block & Co., 770 F.3d 598 (7th Cir. 2014); Schrock v. Learning Curve Int’l, Inc., 586 F.3d 513 (7th Cir. 2009); Specht v. Google Inc., 747 F.3d 929 (7th Cir. 2014); Waterloo Furniture Components, Ltd. v. Haworth, Inc., 467 F.3d 641 (7th Cir. 2006); Wisconsin Alumni Research Found. v. Xenon Pharm., Inc., 591 F.3d 876 (7th Cir. 2010)

Back to top.

18. Amul R. Thapar

U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky (2008 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

U.S. Attorney, Eastern District of Kentucky; Assistant U.S. Attorney, Southern District of Ohio; General Counsel, Equalfooting.com; Assistant U.S. Attorney, District of Columbia; Trial Advocacy Instructor, Georgetown University Law Center; Adjunct Professor, Vanderbilt University Law School; Adjunct Professor, University of Virginia School of Law; Adjunct Professor, Northern Kentucky University, Chase College of Law; Williams & Connolly; Squire Sanders & Dempsey; Adjunct Professor, University of Cincinnati College of Law; Law Clerk to Judge Nathaniel R. Jones (6th Circuit); Law Clerk to Judge S. Arthur Spiegel (S.D. Ohio)

Education

JD, University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law (1994); BS, Boston College (1991)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

1 total (in favor of infringer) |

| Copyright |

1 total (in favor of owner) |

| Trade Secret |

1 total (in favor of owner) |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Cases: Duty Free Americas, Inc. v. Estee Lauder Companies, Inc., 797 F.3d 1248 (11th Cir. 2015); Fastenal Co. v. Crawford, 609 F. Supp. 2d 650 (E.D. Ky. 2009); Rich & Rich P’ship v. Poetman Records USA, Inc., 714 F. Supp. 2d 657 (E.D. Ky. 2010)

Back to top.

19. Timothy M. Tymkovich

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit (2003 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

Hale Hackstaff Tymkovich, LLP; Colorado Solicitor General; Davis Graham & Stubbs; Bradley Campbell Carney & Madsen; Law Clerk to Justice William H. Erickson (Colo. Supreme Court)

Education

JD, University of Colorado School of Law (1982); BA, Colorado College (1979)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

1 total (in favor of owner) |

| Trademark |

5 total (4 in favor of owner; 1 in favor of infringer) |

| Copyright |

6 total (1 in favor of owner; 5 in favor of infringer) |

| Trade Secret |

2 total (1 in favor of owner; 1 in favor of infringer) |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Cases: Australian Gold, Inc. v. Hatfield, 436 F.3d 1228 (10th Cir. 2006); Celebrity Attractions, Inc. v. Okla. City Pub. Prop. Auth., 2016 U.S. App. LEXIS 15244 (10th Cir. Aug. 19, 2016); Cellport Sys., Inc. v. Peiker Acustic GMBH & Co. KG, 762 F.3d 1016 (10th Cir. 2014); Enter. Mgmt. Ltd., Inc. v. Warrick, 717 F.3d 1112 (10th Cir. 2013); La Resolana Architects, PA v. Clay Realtors Angel Fire, 416 F.3d 1195 (10th Cir. 2005); Sportsmans Warehouse, Inc. v. LeBlanc, 311 F. App’x 136 (10th Cir. 2009); Stan Lee Media, Inc. v. Walt Disney Co., 774 F.3d 1292 (10th Cir. 2014); Stan Lee Media, Inc. v. Walt Disney Co., 2015 U.S. App. LEXIS 16055 (10th Cir. May 26, 2015); Storagecraft Tech. Corp. v. Kirby, 744 F.3d 1183 (10th Cir. 2014); Team Tires Plus, Ltd. v. Tires Plus, Inc., 394 F.3d 831 (10th Cir. 2005); Tomelleri v. MEDL Mobile, Inc., 657 F. App’x 793 (10th Cir. 2016); United States v. Shengyang Zhou, 717 F.3d 1139 (10th Cir. 2013); Utah Lighthouse Ministry v. Found. for Apologetic Info. & Research, 527 F.3d 1045 (10th Cir. 2008); Vail Assocs., Inc. v. Vend-Tel-Co., 516 F.3d 853 (10th Cir. 2008)

Back to top.

20. Don R. Willett

Supreme Court of Texas (2005 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

None

Prior Legal Experience

Deputy Texas Attorney General; Deputy Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Policy; Special Assistant to the President and Director of Law and Policy, President George W. Bush; Domestic Policy and Special Projects Adviser, Bush-Cheney 2000 Presidential Campaign; Director of Research and Special Projects, Governor George W. Bush; Haynes & Boone, LLP; Law Clerk to Judge Jerre S. Williams (5th Circuit)

Education

JD, Duke University School of Law (1992); BBA, Baylor University (1988)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

1 (dissenting in favor of state-court jurisdiction for patent negligence suits – a view ultimately adopted by the U.S. Supreme Court) |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Case: Minton v. Gunn, 355 S.W.3d 634 (Tex. 2011)

Back to top.

21. Robert P. Young, Jr.

Michigan Supreme Court (1999 – present)

Prior Judicial Experience

Michigan Court of Appeals (1995 – 1999)

Prior Legal Experience

General Counsel, AAA Michigan; Dickinson, Wright, Moon, Van Dusen & Freeman

Education

JD, Harvard Law School (1977); BA, Harvard College (1974)

Intellectual Property Cases Decided as a Judge

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

1 total (in favor of owner) |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Intellectual Property Cases Argued in Private Practice

| Patent |

0 |

| Trademark |

0 |

| Copyright |

0 |

| Trade Secret |

0 |

Case: Citizens Ins. Co. v. Pro-Seal Serv. Grp., Inc., 477 Mich. 75 (2007)

Back to top.

[1] Professorial Lecturer in Law, George Washington University Law School. The author would like to thank Intellectual Ventures for its invaluable research support.

By Ryan Reynolds

By Ryan Reynolds By Gleb Savich

By Gleb Savich This drinking water crisis disproportionately affects the poor in the developing world. However, problems with access to safe drinking water may arise in any part of the world due to man-made or natural disasters—including in the United States. One recent example is the

This drinking water crisis disproportionately affects the poor in the developing world. However, problems with access to safe drinking water may arise in any part of the world due to man-made or natural disasters—including in the United States. One recent example is the  The pesticide removal technology developed by Dr. Pradeep and his colleagues works by utilizing the ability of

The pesticide removal technology developed by Dr. Pradeep and his colleagues works by utilizing the ability of  Plumpy’Nut® has a long, 2-year shelf-life, is formulated to avoid diarrhea-type side effects, and can be eaten right out of the packet, eliminating the risks of dosage errors and contamination associated with mixing a powder with water. Plumpy’Nut®’s long shelf-life, effectiveness, and ease-of-use have led to a rise in

Plumpy’Nut® has a long, 2-year shelf-life, is formulated to avoid diarrhea-type side effects, and can be eaten right out of the packet, eliminating the risks of dosage errors and contamination associated with mixing a powder with water. Plumpy’Nut®’s long shelf-life, effectiveness, and ease-of-use have led to a rise in  By Mandi Hart

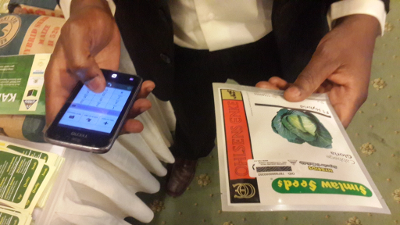

By Mandi Hart In 2007, Ghanaian tech entrepreneur

In 2007, Ghanaian tech entrepreneur  Through the combination of EarlySensor and Goldkeys, mPedigree’s innovative technology is facilitating the protection of both brand owners and consumers and ensuring that data collection and authentication mechanisms are leading to the safer distribution of medicines, cosmetics, seeds, and other essential products.

Through the combination of EarlySensor and Goldkeys, mPedigree’s innovative technology is facilitating the protection of both brand owners and consumers and ensuring that data collection and authentication mechanisms are leading to the safer distribution of medicines, cosmetics, seeds, and other essential products. By providing a dynamic link between consumers and manufacturers, mPedigree is making communications at the point of purchase routine and creating value for consumers, manufacturers, regulatory agencies, and sellers. A project ten years in the making, mPedigree is built on the recognition that protecting intellectual property—both mPedigree’s and its clients—can save lives.

By providing a dynamic link between consumers and manufacturers, mPedigree is making communications at the point of purchase routine and creating value for consumers, manufacturers, regulatory agencies, and sellers. A project ten years in the making, mPedigree is built on the recognition that protecting intellectual property—both mPedigree’s and its clients—can save lives. One promising example of these new mobile diagnostic applications for eye care is the

One promising example of these new mobile diagnostic applications for eye care is the  How does PEEK work? An app and a clip-on adapter

How does PEEK work? An app and a clip-on adapter  CPIP Founders

CPIP Founders

This is the second in a series of posts summarizing CPIP’s 2016 Fall Conference, “Intellectual Property and Global Prosperity.” The Conference was held at Antonin Scalia Law School, George Mason University on October 6-7, 2016. Videos of the conference panels and keynote address, as well as other materials, are available on the

This is the second in a series of posts summarizing CPIP’s 2016 Fall Conference, “Intellectual Property and Global Prosperity.” The Conference was held at Antonin Scalia Law School, George Mason University on October 6-7, 2016. Videos of the conference panels and keynote address, as well as other materials, are available on the  By

By