Notice Number: NOT-MH-20-031

Key Dates

Release Date: February 14, 2020

First Available Due Date: June 05, 2020

Expiration Date: January 08, 2022 Related Announcements

PAR-19-189, Pilot Services Research Grants Not Involving Clinical Trials (R34 Clinical Trial Not Allowed)

PAR-17-264, Innovative Mental Health Services Research Not Involving Clinical Trials (R01)

PA-19-056, NIH Research Project Grant (Parent R01 Clinical Trial Not Allowed)

PA-19-055, Research Project Grant (Parent R01 Clinical Trial Required)

PA-18-350, NIMH Exploratory/Developmental Research Grant (R21 Clinical Trial Not Allowed)

PA-19-052, NIH Small Research Grant Program (Parent R03 Clinical Trial Not Allowed)

RFA-MH-18-700, Clinical Trials to Test the Effectiveness of Treatment, Preventive, and Services Interventions (Collaborative R01 – Clinical Trial Required)

RFA-MH-18-701, Clinical Trials to Test the Effectiveness of Treatment, Preventive, and Services Interventions (R01 Clinical Trial Required)

RFA-MH-18-706, Pilot Effectiveness Trials for Treatment, Preventive and Services Interventions (R34- Clinical Trial Required)

PAR-18-929, High-Priority Areas for Research Leveraging EHR and Large-Scale Data (R01 Clinical Trial Not Allowed)

PA-18-566 Complex Technologies and Therapeutics Development for Mental Health Research and Practice (R43/R44 Clinical Trial Optional)

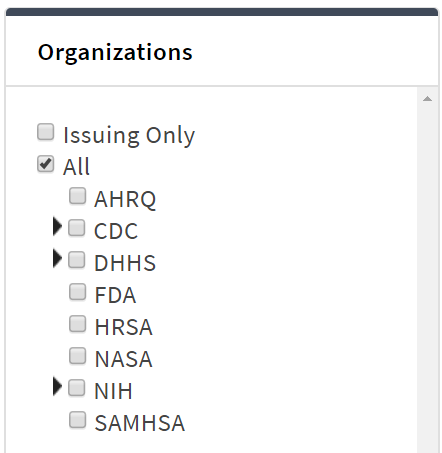

Issued by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

Purpose

Risk identification is a key component of suicide prevention. In healthcare settings, current risk identification is typically obtained through patients’ endorsement of items on screeners, either administered by a clinician or completed by patients through a tablet or via paper/pencil. Another way to identify people with suicide risk is via risk algorithms based on medical record data, which can be considered complementary to the traditional screening associated with clinical encounters in several ways: 1) it does not rely on people to answer questions, it looks at what they have done as opposed to what they say; 2) you can look across a panel of people – not just those seen in face-to-face healthcare contacts.

Risk algorithms have been shown in multiple settings to be a validated way to identify individuals with high suicide risk who warrant additional clinical attention. To date, risk algorithm approaches have not been designed to predict outcomes for individual patients, but rather to assign people into differential tiers of risk. The use of these tools presents some special challenges, including issues around logistics, ethics, and acceptability, and each of these areas present research gaps.

NIMH held a meeting in June 2019 to identify and prioritize research needs in the application of predictive analytics in suicide prevention among healthcare providers. The meeting summary details research topics and gaps that included: biostatistical challenges, provider and patient understanding of risk algorithms, ethical considerations, needs for clinical decision tools to guide risk algorithm application, and policy-relevant research. NIMH is encouraging practice and deployment relevant applications proposed by multidisciplinary teams addressing the following topics:

Biostatistical Challenges:

- Test approaches that could lead to:

- Identifying best practices in the design of the cohorts used to develop risk algorithms, to ensure that the design is suitable for the purpose(s) for which the algorithm is being utilized.

- Identifying best practices in assessing the performance of suicide risk algorithms – including possible effects on equity in treatment and outcomes.

- Examine the benefits and limitations of risk algorithms that consider multiple or composite outcomes, such as risk for non-fatal as well as fatal suicide events, fatal and non-fatal accidents, and others.

- Examine the benefits and limitations of developing and operating multiple risk algorithms for specific subgroups within a larger population/cohort (e.g., those with certain characteristics or experiences, or in certain geographic or care settings), versus one algorithm that is used with the entire population/cohort.

- Develop and test criteria to determine when it might be appropriate to use an algorithm developed in one setting or population/cohort and apply it in a different setting or population/cohort (e.g. if health system B uses an algorithm developed and validated by health system A); versus developing and validating algorithms for each specific setting or population/cohort that seeks to use this approach.

- Compare risk modeling benefits and challenges over alternative time periods, e.g., outcomes within 1 vs. 3 vs. 12 months. For example, if long time periods take place between algorithm calculations, at what point are the outcomes ‘stale’ and less clinically useful?

- Explore whether risk algorithms preserve or – worse – potentially expand disparities in treatment and outcomes; and, if so, develop possible methods to mitigate this.

- What are special considerations for developing risk algorithms for smaller subgroups (e.g., historically disadvantaged groups, sexual minorities, age groups, etc.), such as longer time frames needed and prediction utility?

- Examine the relationships between absolute (predicted) risk, on the one hand, and how identified patients may respond to intervention, on the other. Assess the potential added value of drawing on various types of data in developing risk algorithms, e.g., structured measures from health care claims/encounters and electronic health records, patient-reported measures, measures derived via abstraction or natural language processing from patient care records, measures derived from passive sensor monitoring (e.g., via smartphone); as well as the value of data derived from outside healthcare (e.g., social media, public records, and commercially available data such as credit information, among others).

Provider Understanding, Acceptance and Use of Results from Suicide Risk Algorithms:

- What clinical decision-making data and practical approaches facilitate deciding which risk model to use; what risk strata to intervene on, and how to intervene?

- How could information on potential patient responses to targeted clinical interventions affect how risk algorithm models are developed, and how they are used (e.g., will patients engage in the interventions offered; what are rates of response to the intervention)?

- What are useful approaches to determining when a risk indicator be ‘turned off’ (e.g., indicators of ‘recovery’)

Patient Understanding and Acceptance of Results from Suicide Risk Algorithms, and Ethical Concerns (see also NOT-OD-20-038)

Research is needed that tests approaches to educating patients about risk categories and how clinical care and personal actions may change risk status, with implications for developing healthcare setting best practices in applying risk algorithms to care. When and how are informed consent processes needed when using suicide risk algorithms in practice? Should risk algorithm outcomes be considered PHI for purposed of HIPAA? Practically, how would risk algorithm outcomes be provided in patient portal access (e.g., as a test result with interpretation)? How can patients’ family members/designated significant others, be informed of a patients’ increased risk? Under what circumstances do patients see algorithm use as ‘intrusive,’ or inaccurate (where they may be perpetuating disparities in healthcare services), and what are potential remedies to address these problems?

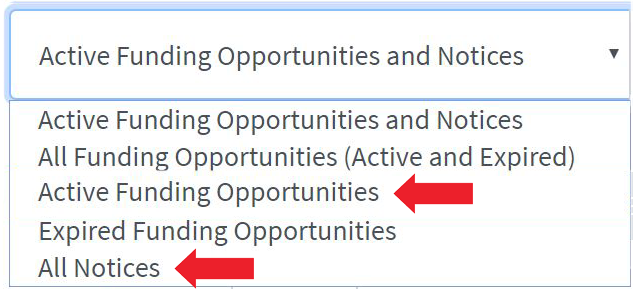

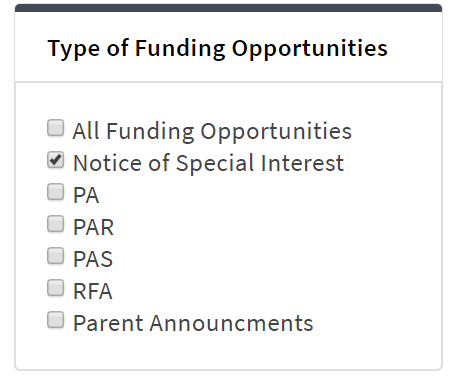

All requirements of the relevant FOA would need to be followed in any application (and award) that proposes to develop and conduct a study on one of these high priority areas. Possible funding opportunities that can be used to pursue these and other research activities include the following FOAs and any re-issuances of these FOAs through the expiration date of this notice. Please note that investigators interested in pursuing clinical trial research should review the NIMH Clinical Trials Funding Opportunity Announcements Website.

Investigators seeking National Death Index Linkage should review NOT-OD-20-057, National Death Index Linkage Access for NIH-Supported Investigators.

Applicants considering such an application are strongly encouraged to consult with NIMH Program Officials prior to submission.

Application and Submission Information

This notice applies to due dates on or after June 5, 2020 and subsequent receipt dates through September 8, 2022.

Submit applications for this initiative using one of the following funding opportunity announcements (FOAs) or any reissues of these announcement through the expiration date of this notice.

R34 – PAR-19-189, Pilot Services Research Grants Not Involving Clinical Trials (R34-Clinical Trial Not Allowed) – First Available Due Date 06/16/2020

R01 – PAR-17-264, Innovative Mental Health Services Research Not Involving Clinical Trials (R01) – First Available Due Date 06/05/2020

R01 – PAR-18-929, High-Priority Areas for Research Leveraging EHR and Large-Scale Data (R01-Clinical Trial Not Allowed) – First Available Due Date 06/05/2020

R01 – PA-19-056, NIH Research Project Grant (Parent R01-Clinical Trial Not Allowed) – First Available Due Date 06/05/2020

R01 – PA-19-055, Research Project Grant (Parent R01-Clinical Trial Required) – First Available Due Date 06/05/2020

R21 – PA-18-350, NIMH Exploratory/Developmental Research Grant (R21-Clinical Trial Not Allowed) – First Available Due Date 06/16/2020

R03 – PA-19-052, NIH Small Research Grant Program (Parent R03- Clinical Trial Not Allowed) – First Available Due Date 06/16/2020

R34 – RFA-MH-18-706, Pilot Effectiveness Trials for Treatment, Preventive and Services Interventions (R34-Clinical Trial Required) – First Available Due Date 06/15/2020

R01 – RFA-MH-18-701, Clinical Trials to Test the Effectiveness of Treatment, Preventive, & Services Interventions (R01-Clinical Trial Required) – First Available Due Date 06/15/2020

R01 – RFA-MH-18-700, Clinical Trials to Test the Effectiveness of Treatment, Preventive, & Services Interventions (Collaborative R01-Clinical Trial Required) – First Available Due Date 06/15/2020

All instructions in the SF424 (R&R) Application Guide and the funding opportunity announcement used for submission must be followed, with the following additions:

- For funding consideration, applicants must include “NOT-MH-20-031” (without quotation marks) in the Agency Routing Identifier field (box 4B) of the SF424 R&R form. Applications without this information in box 4B will not be considered for this initiative.

Applications non-responsive to terms of this NOSI will be not be considered for the NOSI initiative.